THE WET FLANDERS PLAIN

|

|

| First trade edition, Faber, 1929 |

Photographs, postcards and maps

The Wet Flanders Plain (WFP) is a simple, but powerful, tale relating HW’s thoughts on his return to the battlefields of the First World War on two occasions: the first with his wife on their honeymoon in May 1925 and the second with his brother-in-law, William (Bill) Busby, in June 1927. Busby had been in the Tank Corps and had known HW’s cousin Charlie Boon (killed in action on 16 September 1916) – hence Busby’s subsequent marriage to HW’s younger sister Doris (Biddy), who had been deeply in love with Charlie.

The book records the funny, sad, irritating, amusing, and conjured-up memories intermixed with current impressions as they occurred to HW as he made his pilgrimage, with an underlying theme of homage to that host of ghosts: his soldier comrades, known and unknown, who had done service for their country and the ten million men who had given their lives.

HW had very little money on either of his visits and the memory trail is interspersed with grumbles about the cost of meals, beds and travel – a device (similar to Shakespeare) to provide relief to the still-too-close memories of the horror of the war itself.

However, WFP is not just a straightforward diary account of these visits but a carefully crafted and built-up edifice showing ‘then and now’ and the ‘why and wherefore’. The whole is so much greater than the sum of its parts. The thoughts engendered are a provocative (and philosophical) analysis of ‘war’ – its reasons and results.

Many war books were being published at that time as men rushed to write of their experiences (indeed publishers began to feel there was a surfeit): HW’s was different. It is a book which can be read very quickly but should not be: the words need to be savoured for their artistry (an adroit mixture of economy of phrase but powerful image) and to be able to absorb the thoughts that HW has placed as a core sub-text throughout.

* * * * *

In parenthesis, for those unfamiliar with HW’s war service there is a brief outline in the Biography section of this website, and much more information, with a timeline, on the Henry Williamson and the First World War page. Further details can be found as part of AW, Henry Williamson: Tarka and the Last Romantic (1995), but more particularly in AW, A Patriot’s Progress: Henry Williamson and the First World War (1998) (confusion with HW’s own title The Patriot’s Progress caused this first part of the title, meant to echo HW’s thought, to be dropped from the paperback edition). There are also many articles on the subject within the HWS Journal. Indeed, it is almost impossible to write anything about HW without referring to his war experience, so great was its effect on his life and writing.

* * * * *

As stated, The Wet Flanders Plain arose out of two return visits to the battlefields, the first occasion being while on his honeymoon in May 1925. There is nothing within HW’s personal archive to tell us why he decided to make this visit, and it may seem a strange way to spend one’s honeymoon (but they had spent three weeks at a farm on Exmoor first), but we must remember that HW was from the very first planning to write about the war, and it is clear that it was continuously on his mind. His son Richard feels that he needed the support of his new wife to give him the courage to return. Nearly seven years had passed since the war had ended: it was time to face the ever-present ghosts. He would certainly have wanted to refresh his mind about details, particularly about the terrain itself. The dreadful circumstances and atmosphere of battle were indelibly imprinted in his psyche, but there had been little opportunity to grasp an overview of the countryside or to order his thoughts in any comprehensive manner.

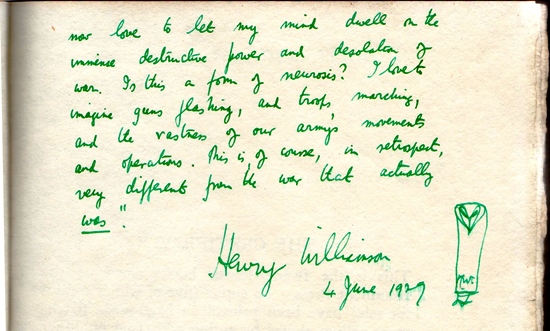

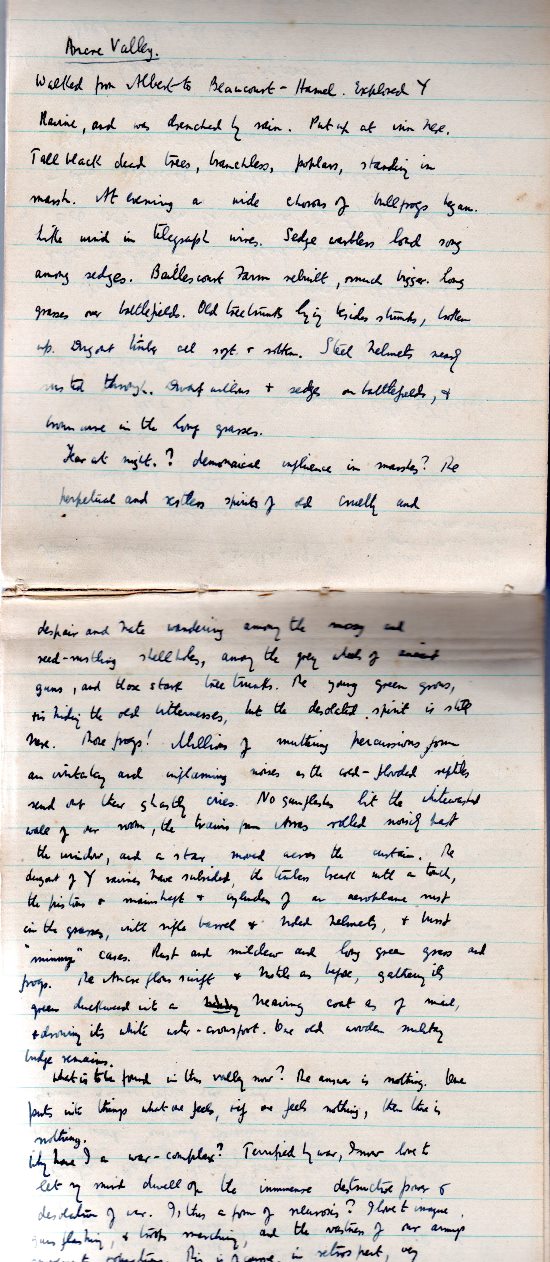

HW wrote this 'Bibliographical Note' in the front of his own copy of The Wet Flanders Plain:

HW kept notes of their honeymoon visit in a small pocket notebook. Having crossed over to France, they evidently took a train down to Amiens, as the first notes are about the cathedral there, and then a branch line across to Albert, the town famous for its ‘Golden Virgin’, the image on top of the cathedral cupola which hung in mid-air throughout the war and was a legend of hope to the troops. After that they seem to have walked. The heading here is ‘Ancre Valley’: the area of HW’s 1917 experience as Transport Officer with 208 Machine Gun Company, and the entry is very detailed. So the headings and notes move on: ‘Hindenburg Line’ – ‘remembered . . . No wonder we failed on May 3, 1917 and afterwards’ (re Bullecourt, see AW, Henry Williamson and the First World War, pp. 112ff. for HW’s movements at that battle, and HWSJ 34, September 1998, where his ‘Orders for the Attack on the Hindenburg Line May 1917’ are reprinted in facsimile, pp. 26-34). Notes for ‘Below Vimy ridge, 28.5.1925’ is a tirade about Arras, ‘a dirty pimply spattered pocked place’. Then ‘Written at Neuville St. Vaast, 28.5.1925’, which are his very powerful thoughts about visiting this German cemetery which appear in the book (and will be discussed later). The notes end there but all these entries appeared in the book in due course.

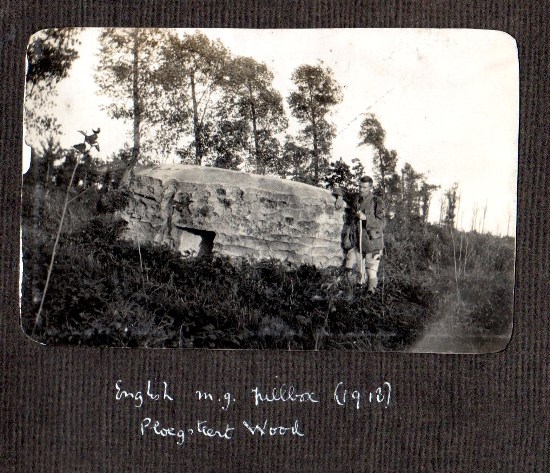

The next page of notes reveals that on 4 November 1926 HW attended, for the first time, a ‘Chyebassa Reunion Dinner’ (the Chyebassa being the boat that took the London Rifle Brigade battalion out to France on 4 November 1914), attended by those of the LRB who had survived the war. HW wrote up notes of this occasion on the page immediately following his honeymoon visit to the battlefields, describing the men whom he had known and notes about their time at ‘Plugstreet’ (Ploegsteert) – including a sketch of the lie of the land. One point he noted was that there was to be an unveiling of a memorial to the LRB at Ploegsteert (the LRB Cemetery lies immediately south-west of the village – which is itself south-west of ‘Plugstreet Wood’) on 19 June the following year. This was probably the impetus that decided HW to make his own visit – his notes are dated 3-10 June 1927. HW does not appear to have attended that unveiling, but the brochure with service notes etc. is in his archive.

Sample pages from the notebook of HW's 1925 visit:

A sample page from the 1927 visit with his brother-in-law:

On his return from the 1927 visit HW prepared some articles, intending that they should defray the expenses of the journey. The Daily Express duly published ‘And This Was Ypres’ over four days, 20-23 July 1927 (reprinted in HWSJ 34, September 1998, pp. 42, 44, 46, and in Stumberleap, and Other Devon Writings, HWS, 2005 (out of print); e-book 2013). But it was not until after the award of the Hawthornden Prize in June 1928 and the imminent tenth anniversary of the Armistice that November that HW’s war articles came into demand. The Daily Telegraph took ‘An Old Soldier at the Battlefields – Memories of a 1914 Journey’ (published on 16 June 1928); ‘An Old Soldier in the Salient – Memories of 1917, Souvenir Hunters at Hill 60’ (23 June 1928); ‘An Old Soldier at Ypres Again – Chorus of Frogs, Reminder of First Gas Attack’ (28 June 1928), and ‘Air Fighting at the Somme – And Hendon’ (a long article on the Hendon Air Show; 2 July 1928); the Evening News printed ‘The Miracle I Saw in France (23 October 1928) and there is an unmarked cutting entitled ‘Fourteen Years After’ (on the German Cemetery).

The Daily Express also commissioned a series entitled ‘The Last 100 Days’ which ran, more or less weekly, from 11 August – 3 November 1928 (reprinted in HWSJ 34, September 1998, pp. 52-65, and in Stumberleap, and Other Devon Writings, HWS, 2005; e-book 2013). This included the very special ‘I Believe in the Men Who Died’ (17 September 1928) – of which more anon.

Brittania magazine printed a full page piece, ‘The Valley’ (9 November 1928).

HW attended the ‘Ten Years Anniversary Remembrance Service’ on 11 November 1928 on behalf of the Daily Mirror, his article, 'Ten Years' Remembrance' appearing the next day (reprinted in HWSJ 18, September 1988, pp. 28-9), while the Radio Times printed his ‘Armistice Day 1928: What We Should Remember and What Forget’ (9 November 1928).

At this point, therefore, HW was getting a great deal of prominence as an ex-soldier writing about the war. He then spent the first two weeks of 1929 on a skiing holiday in the Pyrenees with his friend Kit Williams (Christopher à Becket Williams, composer and writer – who was later characterised in the Chronicle as ‘Becket Scrimgeour’). On his return (16 January) his diary notes that he was working on revisions of his early novels (asked for by John Macrae of Dutton, HW’s American publisher, with whom he had dined in London on New Year’s Day before leaving for the Pyrenees).

For further details about Cyril Beaumont's approach to HW, and the subsequent publication of The Wet Flanders Plain, go to the Publishing history page.

*************************

So we turn to the content of the book itself. It assumes, possibly, some knowledge of the battles and terrain of the First World War, which in 1929 HW probably presumed his readers would have; but so many years later this may not necessarily be so. I have therefore tried to clarify such details within my commentary. Further, Matthews states in his Henry Williamson: A Bibliography that HW noted in a copy that most of the book had been written in 1925. Indeed there is a copy in HW’s archive where he has also added this information. But that is not strictly correct, and it is more complicated than that as will be discovered.

The book opens with a prologue, the very powerful ‘Apologia pro vita mea’ – This is actually the article that had appeared in the Daily Express on17 September 1928, entitled ‘I Believe in the Men Who Died’, where it is described as: ‘this most moving and brilliantly written article . . .’. And then, as part of a series of articles in that paper, it was printed in book form in Is Prayer Answered? I Believe ---. How I Look at Life (Lane Publications, for the Daily Express, 1928), described as ‘Three absorbing subjects discussed by prominent men and women in the columns of the “Daily Express” in three series of articles . . .’

HW’s article was also reprinted in the October 1928 issue of ADAIR MONTHLY: ‘We have received numerous requests from our readers to reprint this article by an ex-soldier of the British Army.’

The re-titling of this essay in WFP sets out HW’s raison d’être – his ‘Apology for his (own) life’: his reason for living, i.e. for surviving the war: to be a voice for those who had died.

‘Apologia’ describes the setting of the peaceful village church (of Georgeham, north Devon) with its gilded memorial to the men of the Parish who fell in the Great War, and then using the powerful crashing experience of being in the belfry when the bells were being rung as an analogy of the battles. Battles which were for ever stamped into his mind, battles in which he did not differentiate between the agony of the ordinary English and German soldiers: for him they were all poor devils caught up in the hell of war – the Lost Generation:

I must return to my old comrades of the Great War – to the brown, the treeless, the flat and grave-set plain of Flanders – to the rolling, heat-miraged downlands of the Somme – for I am dead with them, and they live in me again. There in the beautiful desolation of rush and willow in the forsaken tracts I will renew the truths which have quickened out of their deaths: that human virtues are superior to those of national idolatry, which do not arise from the Spirit: that the sun is universal, and that men are brothers, made for laughter one with another: that we must free the child from all things which maintain the ideals of a commercial nationalism, the ideals which inspired and generated the barrages in which ten million men, their laughter corrupted, perished.

‘Apologia’ is, to my own mind, one of the most – possibly the most – important piece of writing in HW’s whole oeuvre – in his whole ‘life’s work’: certainly it must be read by anyone who wants to understand what underpins HW’s psyche. (I would couple that with his very similar essay ‘Surview and Farewell’ which appears in a later volume.) The association of the church bells (the voice of the church, of religious faith) with ‘I Believe’, the opening words of the Creed, show this to be HW’s own ‘credo’. That is not of course stated openly, but the sub-text message is very powerful.

It is also virtually HW’s first public statement about his deep feelings about what was known at the time as ‘The Great War’ (it was not called ‘The First World War’, of course, until the second disastrous Armageddon).

The book proper is headed ‘THE DIARY’ and is divided into a series of ‘Days’ making the chapters, and then into subheadings of places visited. In order to make the story flow smoothly, HW decided that the first part of the book should cover the second 1927 visit, moving seamlessly into the first (honeymoon) visit about two-thirds the way through. This makes no difference whatsoever to the reader, but I mention it to clarify things for those who already know some of the background. To avoid confusion I intend to follow the course of the book (which in places differs from his original notes), with explanatory commentary. But it is hoped that a full transcript of all HW’s original notes will appear in the HWS journal in the future.

HW’s companion of that 1927 visit, his brother-in-law Bill Busby, is called ‘Four-Toes’ in the book – we are told that he had lost toes due to frost-bite while at the Front.

FIRST DAY

Calais Maritime Station.

Having arrived by boat the pilgrims wait for their train: ‘the old soldier’ sees many things to remind him of the War, or rather he relates the peace time scene before him to its wartime counterpart: the hats people are wearing as similar to regimental caps; the fact that the train is running late – an endemic fact of war; pillows being produced for those bound for Paris (‘Parisites’ is surely a play on ‘parasites’) compared to how the troops were herded virtually like cattle into trucks which had the rather chilling ‘Hommes 40 Chevaux (en long) 8’ written along their sides. But:

The memory of [the war] is purifying and strengthening, as in fire and water the spirit of iron is made into steel.

St. Omer Station.

‘G.H.Q. in 1914. Our battalion detrained here in the autumn of 1914. A sinister and enthralling platform in that early November dusk.’ (The LRB had left for France on 4 November 1914, and had arrived at St Omer on 11 November.) Our author remembers his feelings then, especially those about leaving his mother. It was at the Convent at Wisques outside St Omer that he had first seen the flashes and heard the guns denoting the bombardment taking place around Ypres. This was still the Battle of First Ypres. (Those early war scenes are recreated in How Dear is Life (Vol. 4, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight): details of HW’s actual experience are related in AW, Henry Williamson and the First World War.)

Hazebrouck.

Leaving the train the pair are confused as to the placing of 1914 landmarks; and remember how they were told and thought that the ‘War would be over by Christmas’ – and then that momentous Christmas Truce (not mentioned directly here) ‘when all was friendliness between common khaki and common field grey.’

One hundred years later we are very aware of the force that Truce had on all who took part in it, and for us the particular effect it had on HW, who could never thereafter enjoy Christmas due to his acute reliving of the event itself and its implications. HW does indeed act as a voice for all those thousands of men. (The story of the 1914 Christmas Truce is related in A Fox Under My Cloak, Vol. 5, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, ch. 3, ‘Heilige Nacht’.)

Supper to the Wireless.

‘Hazebrouck is a peaceful town’ (add an ironic silent ‘now’). Hearing the British National Anthem on the wireless as they ate supper, the two men stand to attention, feeling patriotic and proudly superior as ex-soldiers – but as it continued for all its verses, more and more stupid and embarrassed! This leads the author to ruminate: ‘Wars are economic in origin . . . controlled by emotional slogans . . . [by those] giving their young men to the War.’ The day ends with the thankful realisation that although he is in the battlefields:

I am free . . . [I won’t have to] march up the line again, into the agony and desolation of a counter-attack. I can sleep all night.

SECOND DAY

‘Pop’ Station.

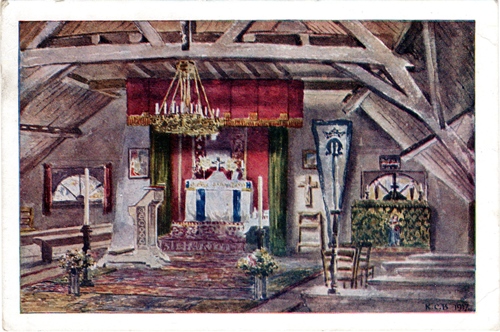

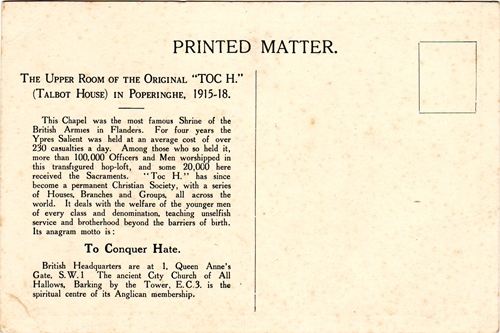

A vivid paragraph tells us the troop trains behaved ‘peculiarly’ at ‘Pop’ (Poperinghe). In effect they speeded up and raced through the station, only stopping half-a-mile beyond it – 17-inch howitzer shells made it too dangerous to stop at the station itself. The two pilgrims walk calmly out of the station to look for Talbot House, where the Army chaplain ‘Tubby’ Clayton had dispensed comfort and cheer to thousands of men on their way to the Front in the chapel set up on the upper floor (previously a hop-loft).

Silence filled the wooden hollow of the loft, with its white-washed rafters, stained brown where rain had dripped through tiles, and its bare smooth floorboards showing the holes gouged by the goat-moth caterpillar in the living trees. Here twenty thousand men had knelt in hope and trust. Twenty thousand souls, bearing names bestowed upon them with pride and tenderness by twenty thousand mothers, clumping up the steep and narrow way, borne there by Hope, and seeking solace at the very verge of unutterable Darkness.

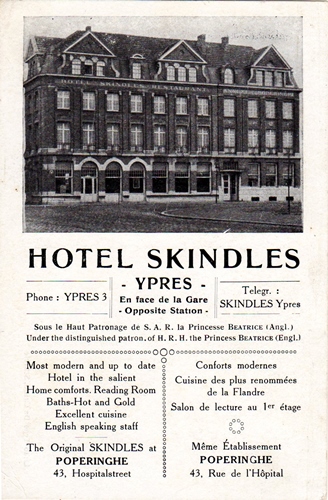

‘Skindles.’

‘Skindles’ was the name given by the troops to the ‘Hôtel de la Bourse du Houblon something or other’ in the Rue de l’Hôpital. The officer of the Rifle Brigade who christened it ‘Skindles’ (as it was known to every soldier) in 1916 was killed a few weeks later in the Somme battle.

This war-time ‘Skindles’ had been too expensive for our author, as was now a new ‘Hôtel Skindles’ – once the Officers’ Club – farther along the street. As also the pseudo ‘Hôtel Skindles’ which had sprung up in Ypres with ‘Baths – Hot and Gold’, as can be seen from HW’s postcard bought on this visit, and rather lampooned by him.

Note the ‘Hot and Gold baths’!

They talk to the ‘Mother of the Soldiers’, the patronne of the genuine Skindles, shown to be empathic, but move on to a cheap establishment (they had very little money) where they were totally stung: extraordinary bad service and food at exorbitant price. The surly crafty patron says ‘C’est la guerre’. In 1925 the war had been over seven years.

The Vlamertinghe Road.

The two men take the long straight road leading east out of ‘Pop’ towards Vlamertinghe, a battle-scarred road taken by thousands of soldiers on their way to Ypres and overlooked by the distant Kemmel Hill (lying a few miles south and a strategic view-point held by the Germans for some time). A few sentences tell us the horror of travelling that road then – but now:

Little trees grow in the gaps between the scarred forefathers of the wayside, as thick as a man’s wrist, and their roots push into the darkness of old unnamed horse-graves. The fields are beautiful with wind-stroked corn . . . Larks sing in the sky, as they have sung during all the years and now we may share in their joyous song of freedom. Their nests are in the tussocks of meadow grass, in the slight hollows . . . where once shells fell, and men among them.

Nature repairs itself very quickly – but man is scarred for ever.

‘Four-toes’ relates the attitude of a politician ‘visiting’ the wounded during the war. ‘I remember reading his eulogy on the optimism and enthusiasm of the soldiers . . .’ So unrelated to the appalling truth of what it was actually like to have been in a tank hit by a shell and bursting into fire.

Vlamertinghe greatly depresses our author: epitomised by the sight of ‘an iron Calvary’ (Jesus on the Cross) on a grassy mound:

. . . a rusty figure of Jesus, in wind and rain, in sunlight and starlight, with new wounds given in this twentieth century of enlightenment . . .

And further by the sad sight of a chaffinch in a tiny cage, blinded to make it sing, just continually ‘hopping up, hopping down, hopping up, hopping down . . .’

The Vlamertinghe–Wipers Road.

They continue towards Ypres (‘Wipers’ to the troops) and can see Wytschaete Ridge (about six miles to the south and about two miles east of Kemmel), and below that, the Messines Ridge, both positions vital to capture from the enemy and the scene of fierce fighting.

‘Goldfish’ Chateau.

They pass the site of the Divisional Headquarters (nicknamed ‘Goldfish Chateau’), which had survived throughout the war only to be blasted out of existence two years later when thieves, stealing metal off the vast pile of shells dumped there, grew careless and a huge explosion resulted.

Ypres.

Ypres is unrecognizable: Wipers exists in the memory only. The city today is clean and new and hybrid-English. Its vast Grand’ Place holds enough air and sunlight to give a feeling of freedom and space.

It must have been quite a shock to see how the old town had risen from a pile of rubble back into an image of its pre-war self. It was an amazing feat to rebuild – and so quickly: but HW obviously found it disturbing. He comments several times about the new buildings that abound everywhere.

He quotes, with some wry amusement, from a handbill advertising coach visits to see the battlefields and cars for hire: carefully preserved, the single page ‘brochure’ still exists all these years later.

You need to read HW’s comments to capture the irony of his humour. But the humour has a deeper side as he shows the folly of laying both the blame for death in the war and praise for Victory at the feet of God. The message is that the responsibility lies only with man himself. We are responsible for our own actions and those that make decisions are accountable (quite chilling when applied to modern wars).

Evening on the Ramparts.

(HW’s notes for this section are dated 6 June 1927.) That the new Menin Gate Memorial was in place is obvious, although it was not inaugurated until 27 July 1927. The Memorial straddles the eastern exit road where it crosses the wide canal which ‘moats’ the town. This is the road that soldiers took as they left for the (Ypres) Salient – and to Passchendaele (Third Battle of Ypres, 1917) about 6 miles north-east. At that time this was merely a gap in the ancient ramparts through which they passed. (The road actually leads to Menin, a small village about 10 miles south-east.) Those who defended Ypres were extremely proud of the fact that the town was never captured by the Germans.

| The Menin Gate – a postcard sent to HW in 1957 |

The Menin Gate Memorial is inscribed with thousands of names of those who died in the Salient and have no known grave: even this huge edifice was found in the end not big enough for all – many are therefore recorded at the Tyne Cot Memorial.

| Tyne Cot Cemetery, Passchendaele – a postcard send to HW in 1971 |

Every evening since the inauguration (apart from the years of the Second World War), with solemnity, dignity, and total dedicated sincerity, the people of Ypres provide the opportunity for those present (and every night there is a gathering of visitors who come from all over the world) to pay tribute to those who died in a simple but very moving ceremony: prayers are said, wreaths are laid, the Last Post is sounded.

Members of the Henry Williamson Society have been privileged to attend this Ceremony on several occasions when wreaths have been laid on behalf of HW and the regiments in which he served – the LRB, and MGC, and the Bedfordshires.

| Members of the Williamson family at Menin Gate, July 2010 |

It will soon be one hundred years since the ceremony was inaugurated: surely this has to be one of the modern ‘Wonders of the World’ – perhaps THE modern wonder. The people of Ypres do not forget, and those responsible for organising the myriad behind-the-scenes details are totally dedicated, and their genuine kindness, goodness and humour shine out. It is a ceremony from which one leaves feeling truly better for the experience, and we owe the people of Ypres a great deal.

But these massive memorials that are constantly in the public media – Menin, Tyne Cot, and Thiepval on the Somme – have hundreds of smaller counterparts in the actual cemeteries that lie beside every road in the area, all filled with the official white headstones inscribed with name, rank, regiment and the simplest commemorations: row upon row upon row.

Here in WFP, HW does his remembering on the ramparts that rear up out of the protective canal:

I walked on the ramparts with another man – the wraith of my old (or my very young) self. . . . a force is passing, an invisible wind that hurls down the stones and the bricks soundlessly, that fills the Grand’ Place and all the streets with cries and shouts and the last screams of the dying, and yet all is without sound.

These overpowering images follow him into the cafe where ‘Four-toes’ is waiting:

I am a wraith again in the darkness rushing by . . . the viewless white flashes of field guns lighting the broken wall and the scattered rubble; the misery of men marching, laden and sweating, through the ruin of the Menin Gate. Passing strings of men slouching away from the line, thinking only of sleep, sleep, sleep.

Only a man who had experienced these horrors of battle could write with such authenticity: only a writer of HW’s calibre could have expressed them with such clarity.

THIRD DAY

A Charabanc Ride round the Salient.

(All the little landmarks that they pass as they travel can be found on HW’s detailed map of the area: see Personal photographs and maps page – though unfortunately the scale of the latter has had to be reduced.)

Our two pilgrims join a Divisional Commemoration gathering (we are not given details of whom in the book – nor are there any in the pocket notebook) who are travelling by charabanc to unveil a memorial at Langemarck (some six miles or so north – slightly north-east – of Ypres. This is Third Battle of Ypres area: Passchendaele village itself is about 4 miles east of Langemarck.)

We stood silent and bare-headed before the Memorial, on ground but lately a horror of manifold agonies suffered by men who had not wanted to do the things they had done, . . . men who had suffered agonies which were now of Glory, Sacrifice, Heroism, Patriotism – all the abstract ideas which Europe still suffered her children to be taught.

On their return to Ypres the pair are invited to have lunch with the charabanc party (soup, beer, pigeon, salad, compôte of fruit, cream, coffee): ‘Four-Toes’ felt ‘that made up for yesterday’s lunch’ (the fearfully expensive uneatable mess in Poperinghe).

HW’s original notes do not record this event: one suspects that the two travellers actually took one of those advertised charabanc tours on the brochure!

HW records the crassness of an American visitor following a ‘list of things to see and do’.

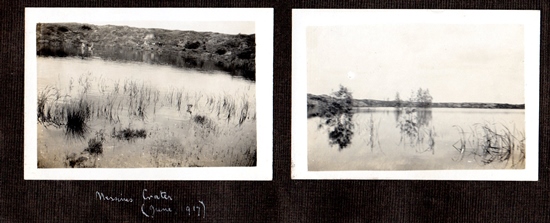

We have another Free Ride.

After lunch they are invited to continue with this group to Kemmel and on to Wytschaete and Messines (they travel via Poperinghe which seems strange – their destination being actually 6 miles directly south) to see the nineteen mine craters created by the underground explosions prepared over six months’ desperately dangerous work by the tunnellers on 1 June 1917 when ten thousand Germans were killed, thousands more wounded, and over 7000 taken prisoner. On HW’s visit these craters (at least 100 yards across, some more) were filled with water and the home of frogs.

FOURTH DAY

Afternoon on the Ramparts.

Taking things easy (as Four-Toes’ feet are sore) HW ruminates in a lyrical passage, lying on the brickwork which binds the ramparts of Ypres ‘among the tall, wild grasses’ and watches a reed-warbler on the other side of the canal and a family of coots. He contrasts the water then and now:

Today it is beautiful and tranquil, shining with the white and blue of the sky. . . . [mentions a swallow, jackdaws – and strange noise of frogs] . . .

Once there were like noises in the throats of men staggering down from the first gas attack. . . .

How sweet a thing it is to be alive and free in the sunlight, among the fair grasses of summer, watching the swallows’ wings gleaming blue above the water.

FIFTH DAY

Passchendaele Ridge. [Third Ypres – or Passchendaele: October – 6 November 1917]

From here you may look down over the Salient, in silence as your mind goes back to those days.

One feels it is all too terrible to put into words. HW is, of course, looking at a scene in which he did not take part, but he knew only too well how bloody that battle had been – for both sides – the New Zealanders, Australians and Canadians taking the brunt for the Allies: their Memorials, including Tyne Cot, dominate the area testifying to the cost of gaining the pile of rubble that had been Passchendaele.

Hill 60. (Some scant 3 miles south-east Ypres, beside the main railway line)

is one of the show places of the Salient today . . . now set with a small memorial to the 9th London Regiment, and dug over, and strolled over by 10,000 people every week.

Again he is quite sarcastic about the behaviour of American visitors.

The Salient Now – and Then.

‘The Salient’ is the recognised name for the fortified line held around Ypres throughout the First World War – the town proud that it was never occupied by the Germans. The author allows his innermost thoughts to surface.

Flatness of green fields, no tall trees anywhere, clusters of red-tiled, red-bricked farms and houses, and a dim village-line on the far horizon, only very slightly higher, it seems, than the green flatness everywhere – that is the Salient today. Yet for years these few square miles were shapeless as the ingredients of a Christmas pudding while being stirred. Not even worms were left after the bombardments – all blasted to shreds, with the bricks of ruins, stumps of trees, and metalling of roads. . . . Mankind suffered over a million casualties within the dish, double-rimmed with inner and outer ‘ridges’ of the Salient. . . .

The only way over the morass was by the wooden tracks that serpentine over the mud . . . looking like the slough cast by monsters of the primeval slime.

It is a powerful passage – a painting in prose as powerful as any image by the war artists.

The Genius of the Salient.

Near St. Julien, opposite Triangle Farm at a place called Vancouver . . .

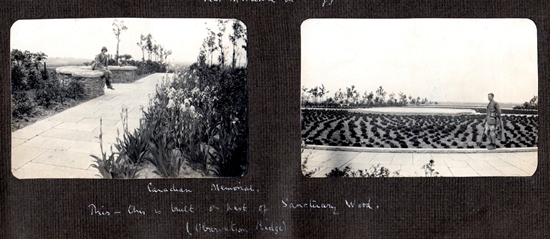

The author has taken us north again to just south-east of Langemarck, to mention what for him was ‘the most beautiful thing in the Salient’ – the Canadian Memorial, which for HW was:

the memorial for all the soldiers in the War’. . . . It mourns; but it mourns for all mankind. We are silent before it, as we are before the stone figures of the Greeks. . . . The genius of Man rises out of the stone, and our tears fall before it.

SIXTH DAY

We Buy Cigars.

Counting their money the two men find they have little left – mainly due to a ‘binge’ before leaving Ypres – and HW mentions an ‘Extraordinary Adventure of the Barber of Ypres’ to be told elsewhere in due course. I’m not sure that that ever happened – but his notebook contains over two pages of rather wild notes about this interesting character!

They had also each bought a box of 50 cigars for 40 francs a box – which we learn later promptly get confiscated by a wily guard when they cross the border into France.

Now they leave to take the train, passing the ‘Hotel Skindles’ of ‘Gold Bath’ fame where they had so generously been included in the free luncheon, en route for a ‘slow ride to Messines’: via ‘Kruisstraathoek, Vierstraat, Kemmel and Wytschaete’

I cannot see that any such rail link actually existed (it is certainly not marked on his detailed map dated 1924). I have found these places on his map – but they zigzag about rather! If such a journey took place then it was perhaps by bus. It would seem that HW is almost certainly using this as a means to link what now becomes the story of his original 1925 honeymoon visit. He and Busby did not go south on their 1927 visit. The author does more or less tell us this as he states that his tale of

The Rude Men [of Wytschaete].

does not belong to this tour with Four-Toes, but to another visit.

Thus ‘a tired English pilgrim and his young wife’ were HW and his bride on their 1925 honeymoon visit. The tale tells of derring-do of our author in overcoming four young Belgians who make lewd gestures and remarks to the English pair. This is of course embroidery from a ‘Don Quixote’ imagination! (As HW admits in his MS notes shown earlier.) In the 1925 Notebook all that our author wrote about Wytschaete was:

Listened to bloody degenerate lache Belgians in a café on Whit Monday’

[‘lache’ translates as ‘slovenly’ but HW puts more venom into it than that!]

The Maedelstede Farm that he mentions in WFP is marked on the map about half a mile due west of Wytschaete. But this tale is told as an ‘aside’ – here our pilgrims continue.

‘Plugstreet.’

The pair (in WFP this is still HW and ‘Four-Toes’) walk from Messines (Mesen on modern maps) to Ploegsteert Wood via ‘St. Ives’ (marked on the north-east corner of the wood) and we learn that the R.A.M.C. – the Royal Army Medical Corps – were cheerfully known as ‘Rob All My Comrades’!

This is the place where HW had his first experience of war in that dreadful winter of 1914 as a private with the London Rifle Brigade.

Today the wood is unrecognizable, the old redoubts and corduroy paths undiscoverable. The brasseries, where we bathed in the vats while the winter wind scoured through the slats upon our nakedness, is gone for ever, and the wood is filled with graves. Its spirit lives on only in memory; with us it will die, so we walk on.

Its spirit has not died of course: through his later writings in How Dear is Life and A Fox Under My Cloak, which describe in detail this early period of HW’s experiences of WWI, it certainly lives on – for all who read his words with true empathy.

The HWS has visited ‘Plugstreet Wood’, walking to Rifle House Cemetary in the middle, where it is set in a glade. White Admiral butterflies glided among the dappled shade, sipping the nectar from blackberry flowers. A place that had known the most hellish horror, but with time healed by nature – and surely by the spirit of those visiting it with peace in their hearts and minds, as has happened throughout the battlefields.

We are then told how the cigars were confiscated as they crossed the border into France – a lucrative perk for the border guards! But at the end of this section the author relates that ‘Four-Toes could hardly walk and so returned to England.

SEVENTH DAY

Arras.

That the tale has now reverted to the 1925 visit is completely invisible to the reader. The description of the pilgrimage moves seamlessly on, after a brief résumé of the awful hotel in Arras, with the author now apparently on his own. (Those interested in such matters will have noted that he is actually describing the 1925 visit in reverse, as on that visit he started from the south, at Amiens, and journeyed east and north.)

HW obviously did not take to Arras as he states:

as can be seen from the following entry in my note-book which I made half an hour later:

Below Vimy Ridge, 28th May. Written during intervals of scratching.

Arras is a dirty, pimply, spattered, pocked place . . .

He uses the word ‘scoriae’ – the debris of beetles: doubtless in his mind referring to the scratching (not in his original notes) from bed bugs from his rather awful night’s lodging.

He also felt, from what he saw all around him, that everyone had done quite well out of ‘Dommage de Guerre’ – without thought of the cost of life that was the real ‘dommage de guerre’: ‘dommage’ translating as both ‘damages’ and ‘pity’. One must remember that his feelings would have been extremely sensitive as he travelled this route for the first time.

On the Heights of Vimy.

That bitter mood passes as HW walked up the ‘long gradual slope’ to the ‘crest’ of Vimy ridge. The scene calms him as he pottered about in ‘a dream of memory’, a gently grazing bull and cow filling him with a ‘tranquil happiness’.

Vimy Ridge was taken by the Canadians in April 1917 at an enormous cost of life. Today the Ridge is dominated by the huge Memorial to all the Canadian soldiers killed in the war, giving a solemn grandeur to the surrounding countryside. But that same blurred, misty, smoky, view of the distance described by HW is still there. The feeling is perhaps, not so much one of tranquillity, but of a sombre and brooding resonance.

EIGHTH DAY

The Widow of Roclincourt.

A simple tale of human tragedy: la veuve Marchand (the 1925 notebook reveals her name, not told us in the book) whose son had been killed in the war and whose living is now made by looking after the English gardeners looking after the cemetery. I will quote here from his journal notes – as for once they are more poignant than the book itself:

Poor little veuve, her son’s portrait (enlarged from a snap) looks down from the wall. She has a splendid cooking range, porcelain & enamel faced, with a design of birds and flowers; but no son.

The printed version replaces the last three words with:

And when she returns to her kitchen she is proud again in her fine new house.

La Maison Blanche.

A short description of the Canadian underground HQ, where many maple leaves and names are carved into the chalk – a most ghostly scene – is word for word as in his 1925 notebook.

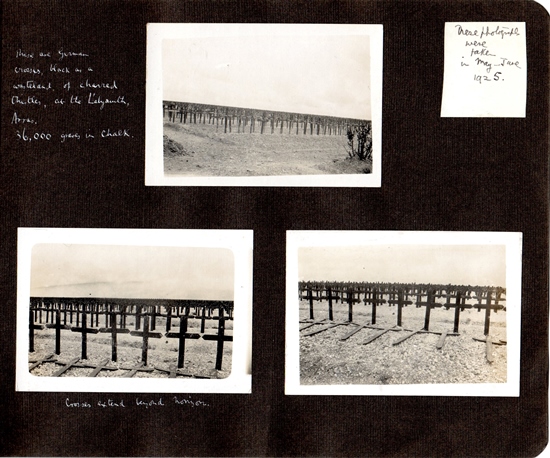

The Labyrinthe.

A German redoubt (stronghold) which was the scene of fierce fighting in 1915:

The French, who attacked, perished in far greater numbers than the Germans.

HW’s passage here in WFP is rather obscure (both then and now) without some background knowledge. He digresses to tell the reader about a book which had made a huge impression on him and which he felt epitomised the war: Le Feu, by Henri Barbusse (1916; English edition Under Fire, 1917), written while he was recovering from wounds in hospital. Barbusse was already an experienced, but controversial, writer when war broke out. His experiences of war gave rise to powerful thoughts about it (‘The peoples of the world ought to come to an understanding . . . all the masses ought to come together . . . All men ought to be equal . . . and there’ll no longer be appalling things done in the face of heaven by thirty million men who don’t wish them . . . [due to] – financiers, speculators . . . who live on war and live in peace during war . . . their faces shut up like safes’) which equated with HW’s own ideas. Barbusse was of the far left as was HW for many years after the war.

(Further information can be found in the sources already quoted. HW himself expounds on Le Feu in his essay ‘Reality in War Literature’ in Linhay on the Downs and Other Stories.)

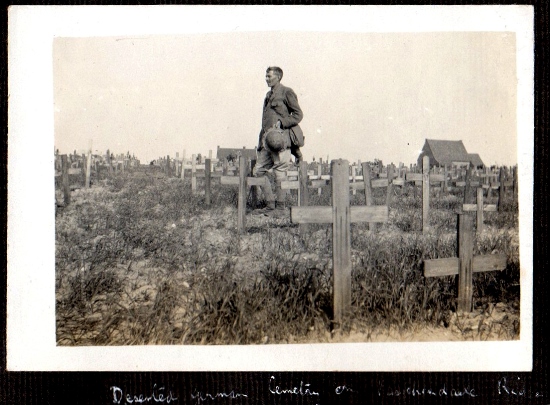

HW continues with his thoughts about the fighting around and for ‘the Labyrinthe’. But he is brought up short as he comes across the German Cemetery:

For, packed close together, and in pairs, back to back, the crosses that are planted in the bare chalk are a vast and terrible sight. Acres of crosses, acres of blackness, nearly 100,000 tall black symbols of crucifixion . . .

Black, black, black, vast and terrible, the charred forest sweeps over the horizon.

The HW Society recently visited the German Cemetery at Neuville St Vaast. Black crosses still stand there row upon row. We read HW’s words and then wandered among the graves as surely he had done, reading names, ranks, regiments (and noting several Jewish stars among the mass). Set about with trees as in an orchard there was a tangible air of peace almost more potent than in the hundreds of white-graved cemeteries of the British dead. It is one of very few German Cemeteries in the battlefields. Most German dead were dug up and returned to their homeland: HW witnessed this taking place on his visit and it troubled him. Continuing, as did HW, we too saw across the road a little further on the equally massive cemetery of the French dead. HW wrote:

Many French died here in the early days, many more French than Germans; but they all suffered to the very core of their beings . . . I know. I was a soldier of the line.

HW asks us to have compassion on all who took part in the war – the dead and the living, whatever their nationality. He felt all were victims of a system of entrenched ideas that gave rise to war. His thinking was based on the humanity of man for man.

Here this is reinforced as he continues and finds ‘a single cross of poplar’ made by a ploughman to commemorate an unknown German soldier he had unearthed in his work. An act of common humanity:

Now the stick is a little tree, with many grey-green rustling leaves; the wilderness has blossomed.

Two black poplars (unusual trees for England – common on the battlefields) that grew opposite HW’s home at 11, Eastern Road, Brockley, are thought perhaps to have been planted by HW. There is no proof of this – but the coincidence is surely too great for it to have been otherwise? He could so easily have taken slips at this moment. (Recently felled, there is a suggestion that two new trees should be planted in their place and dedicated to HW – which would be a wonderful gesture.)

Written in sunlit evening cornfields (from Diary).

Our author is now in the area of his 1917 experience as Transport Officer at the Front:

Remembered.

The text is indeed more or less word for word from his original notebook apart from an added:

April and May 1917, failure, and then failure, and then failure. Fifteen assaults in three weeks.

HW’s subject here is the attack on the Hindenburg Line in which he had taken part. (His copy of the Orders for the Attack are reprinted facsimile in HWSJ 34, September 1998.) Now, on a calm sunlit evening he can see the lie of the land and the all too visible remains of the blockhouses marking the Hindenburg Line. He speaks to an old man working in the fields, who cries out:

‘LA LIGNE INDENBOO-OOR-R-R-K FINIE !!’

and bent again to the tilling of the field . . .

LAST DAY

Disinterring the Dead at St. Leger.

St. Leger, a tiny hamlet, lies just south of Croisilles. Here HW watched German bodies being removed from their graves to be transported elsewhere. The implication is without any due respect – in contrast to those English who had died in German hands and had been buried with care and marked:

‘Here rests in God an unknown English soldier.’

. . . in wartime friend and foe were often buried together. . . . The bones of the slain may lie side-by-side at peace in war-time, but in peace-time they are religiously separated into nations again, each to its place: the British to the white gardens . . . and the others to – the Labyrinthe.

This is all disturbing him greatly and he returns to his thoughts at the German Cemetery where the graves are:

Black as thistles – the unwanted thistles that the farmer and his wife uproot . . . Black as a burned place, bitter and black as frost or fire, a frost of silence among the black crosses.

Once these were men who, having marched where they were ordered, and having done what commanded, after endurance and suffering, fell, and were lost.

HW’s cry for humanity, for the pity of war, its origins and its consequences, is surely a prose passage comparable to that famous poetic cry of Wilfred Owen.

He wanders around this area, mentioning villages that he had known during the war.

Miraumont.

The village was flooded when I was last here . . .

His 1917 diary note reads: ‘Monday 12 March: Am taking ammunition through Miraumont tonight . . . took 16 pack mules . . . got lost. Lost 2 mules. Arrived back at 3 o’clock dead beat.’ And on 22 March 1917: ‘Moved in evening to Miraumont. Arr’d 12 midnight.’

As he eats an omelette in the estaminet surrounded by seemingly hostile locals he mentions he wants to write a book like Henri Barbusse. The men gather round suddenly animated and tell of a German ex-soldier who had visited who had also read Barbusse: so they felt he had been one of them – a ‘comrade’, a ‘brother’. The terms ‘brother’ and ‘comrade’ would of course have had more meaning than is apparent – due to Barbusse’s communistic leanings – and no doubt those of the local men. That HW was a follower of Lenin at this point is revealed in The Pathway, published a year earlier (1928) than The Wet Flanders Plain.

The Valley of the Ancre.

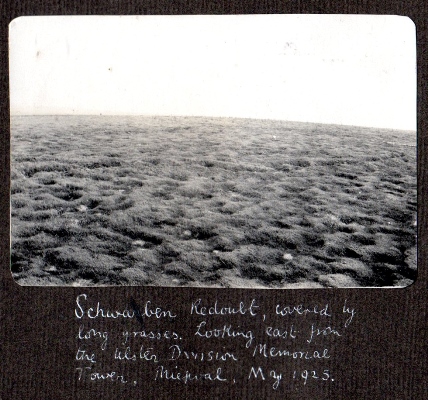

The Germans in their Schwaben Redoubt (stronghold) had mown down the men of the Ulster division where now stands the Ulster Memorial Tower, described by HW as looking:

. . . like a giant hand severed at the wrist and upheld as a warning.

While the trenches:

. . . filled me with indescribable emotion – the haunting of ancient sunlight.

He walks on to:

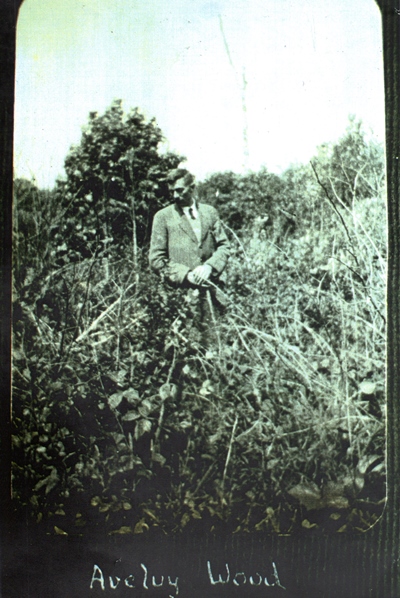

‘Av-er-loy Wood.’ (Aveluy Wood)

The young man of my old self used to walk along this road . . . an alien waste place, with the dead still unburied in the shell-craters on either side. Now the wood is green, and the new growth is twelve feet high.

He hears a blackbird and a nightingale and remembers the sad tale of a cuckoo rescued by a ‘fair and gentle’ soldier, but after the war wantonly killed when it returned to its place of succour.

Stirred to tears by the spirit of ancient sunlight, I dreamed of [the soldier] walking in other fields, where there were no scars of shellholes; and his cuckoo was with him.

Two small comments to make here: firstly, the obvious references to Richard Jefferies with ‘ancient sunlight’ – the concept of which HW took onto himself and which was to imbue his much later Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight. Secondly, remember that as HW has actually been tracking backwards from his actual pilgrimage – so these impressions here were actually among the first he recorded.

But further, interestingly, there is a passage in Tarka the Otter which absolutely echoes the one above:

Tarka slept, and he dreamed of a journey with Tarquol down to a strange sea, where they were never hungry, and never hunted. [The last words of chapter 17.]

And so farewell.

My comrades died in the cellars and rubble of this town, which was destroyed and made fetid by the German guns away over the hills enclosing the marshy valley.

HW is in Albert (name not mentioned), straddled across the River Ancre a few miles before it joins the Somme. This is where he had left the branch line train from Armentieres to actually begin his honeymoon walking tour on May 25 1925, where the notebook states: ‘Ancre Valley. Walked from Albert . . .’. Here the frogs disturb his sleep as if:

A demoniacal influence in the marsh, materializing out of the harsh, ceaseless croaking among the stumps of the dead poplars . . . [but] no white gun-flashes lit the walls of the room . . .

The Ancre flowed in its chalky bed, swift and cold as before . . . a voice seemed to say, a voice of the wan star. ‘What you seek is lost for ever in ancient sunlight, which rises again as Truth.’ The voice wandered thinner than memory, and was gone with the star under the horizon.

Here direct reference to Jefferies’ ‘ancient sunlight’ again – but also another in ‘the wan star’ which features in his book The Star-born.

And so HW says farewell to the battlefields as he returns to his home in Devon. These 1929 words state that he has laid his ghosts:

When I awoke next morning the wraiths were fled . . . the new part of myself, overlaying the wraith of that lost for ever.

That was not actually so. His experiences of the First World War never left him, and dominated his thought processes throughout his life.

| Albert – the Golden Virgin |

Photographs, postcards and maps