THE WEEKLY DISPATCH

(HW’s contributions to this Sunday newspaper)

|

|

| Privately printed edition, 1969 | |

|

|

| Reprinted, HWS, 1983 | |

|

|

| E-book edition, HWS, 2013 |

Introduction to the 2013 e-book edition

Collected, edited and printed by John Gregory, 1969 (7 copies only)

Reprinted by the Henry Williamson Society, paperback, 60 pp, 1983

Revised edition, e-book only, HWS, 2013

This small booklet comprises the articles that HW wrote for The Weekly Dispatch during the period July 1920 to 2 January 1921 when employed by the editor Bernard Falk, and carefully gathered together by John Gregory in 1969, with HW's approval. The background to this ‘labour of love’ is explained in the introductions to the 1983 and 2013 editions.

Having been demobilised on 9 September 1919, HW subsequently found it very difficult to adjust to civilian life, although he was already writing hard. He was in a state of deep nervous tension, verging on breakdown, from his experiences in the First World War and found life in the family home with its restrictions and criticisms extremely irritating. His maternal grandfather, Thomas Leaver, a director of a large stationery firm in Rosebery Avenue, in the Holborn area of London, approached (via a colleague, Vansittart Bowater, of the paper firm) Lord Northcliffe of The Times newspaper, and obtained for HW a job as a canvasser in the Classified Advertisement Department. HW did not find this work congenial, but it did provide him with a good introduction to Fleet Street and the ways of that world.

He was soon placing short items in various newspapers, and in July 1920 was given the chance to produce ‘On the road’ a short weekly column of ‘light car’ notes in The Weekly Dispatch; he supplemented these with other stories, some real and some made-up, and a few nature sketches under the title of ‘The Country Week’.

However, The Weekly Dispatch was in financial difficulty and unfortunately (or possibly fortunately!) HW was dismissed, the work finally drying up as the year turned into 1921. His journal records that he was paid £2/2/- (2 guineas) a week, which would seem to have been quite a good rate. HW wrote an evocative essay of his time as a novice reporter, ‘The Confessions of a Fake Merchant’, which was first published in The Book of Fleet Street (1930), edited by T. Michael Pope, and reprinted in HWS journals nos. 8 and 9 (1983/84).

This collection is of great importance in the hierarchy of HW’s writing career, and we are indebted to John Gregory for the patience, time and diligence with which he has pursued his self-appointed task of collecting together, not just this slim volume, but over many years the major part of HW’s articles and essays published in a variety of publications on an amazing range of subjects: giving us an equally amazing series of book titles.

The Weekly Dispatch articles are interesting as illuminating, as if snapshots, life in 1920, but particularly they give us an insight into HW’s growth as a writer.

The collection was revised and reissued by the HWS in 2013, with a new introduction by John Gregory, as an e-book, with the new title of On the Road, this column forming the major part of the book.

HW stuck cuttings of some of these early efforts in newspapers such as the Evening News and Observer, as well as the Weekly Dispatch – some amusingly marked ‘true’ or ‘fake’ – in his ‘Richard Jefferies’ journal, in which he recorded his thoughts from February 1920 to mid 1922, as illustrated below:

********************

(The Introduction below is from the e-book edition published in 2013, and is a revised version of the original.)

Henry Williamson, who wrote over fifty books, is best known today to most people as a ‘nature writer’ – author of the classic books Tarka the Otter and Salar the Salmon – and to others as the author of the 15-volume A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, a magnificent panoramic history of the first half of the twentieth century, and the First World War in particular, viewed through the character of Phillip Maddison.

On the Road collects his very earliest published writing, as a green young journalist on the Weekly Dispatch, which he joined not long after he was demobilised from the army.

Henry, who was born in 1895, served throughout the First World War, being present at the famous Christmas Truce in 1914 as a private in the London Rifle Brigade, and ending the war as a lieutenant in the Bedfordshire Regiment.

We know that even while Henry was still in the army he had begun to write. He was not demobilised until September 1919, almost a year after the Armistice, ten months during which life must have seemed lonely and flat, both for him and hundreds of thousands of other young men then in the armed forces. Joining the army, and going to war often straight from school, it was the only adult life that many had known. Henry has described how, during the latter part of that period after the Armistice, when he was with the reserve battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment, then stationed at Cannock Chase in the Midlands, ‘I discovered myself as a writer, and spent my days in my asbestos cubicle writing, and reading Galsworthy, Shakespeare, Shelley, and Richard Jefferies . . . I wanted to write the truth as I had seen it . . . so I stayed in my cubicle, eating biscuits and making tea.’ Not surprisingly this behaviour was not condoned by his immediate superiors, and it hastened his departure from the army.

Henry left the army with not very much – his new Norton motorcycle, a Brooklands Road Special which cost him seventy-nine guineas, and what was left of his gratuity after buying it, together with a small disability pension. He also left the army, in his own words, ‘without the least intention of doing any work for a living, except by writing my own kind of writing’.

Henry used to write at night, in his uncle’s old bedroom in the house next door to his parents, and would loaf about during the day, much to his father’s annoyance and frustration – perhaps understandably, for as far as he could see his son was a wastrel, doing no work and earning no money. However, Henry’s gratuity did not last long – he either spent it or lent it to friends (and never seemed to be paid back) – and this hastened his advent into Fleet Street, for until he could make money by his kind of writing some kind of income became a necessity.

His first job was obtained partly through the efforts of his grandfather, Thomas Leaver, and this was as a canvasser for the Classified Ads department of The Times, owned by Lord Northcliffe, in January 1920. The job must have lasted some six months – six months of tramping the streets of the suburbs of north London, during which time, Henry says, he ‘adopted a humble and almost obsequious manner, creeping into the offices of estate agents, and trying to avoid having the junior clerks come towards me as though I were an important client’.

Exactly when he left this job is not clear, but Henry mentions it as being ‘towards the heat of the year, after a holiday in my Devon cottage’. The Manager of Classified Ads approached him and asked if he knew anything about light-cars. ‘No,’ Henry replied, ‘but I’ve got a racing motorcycle.’

That was experience enough. The word was that Northcliffe – the Chief – was not pleased with the light car notes then appearing in the Weekly Dispatch, and a replacement was required. The word had gone out.

The ‘light car’ was exactly that, in those early days of motoring. They were, together with cycle-cars, seen as a preferred alternative (as offering both some shelter from the elements and side-by-side companionship) to the motor-cycle and sidecar combination. They were really no more than motorcycles on four wheels, fragile-looking devices, usually powered by motorcycle engines. Many of the light car manufacturers that sprang up after the war provided what were very basic cars indeed, with the purchaser expected – and indeed expecting – to do his own maintenance and running repairs. They had a light chassis, thin spoked wheels – motorcycle wheels – and more often than not a pressed fibreboard open body which might, if you were lucky, survive a rainstorm without disintegrating. Light cars were subject to a reduced tax, and the theory was that they would be cheap to build, very economical to run, and so provide motoring for the masses. Most of the post-war light car manufacturers, woefully under-capitalised, vanished as quickly as they had arrived, and the light car as a class was killed stone dead by the arrival of the Austin 7.

The editor of the Weekly Dispatch at that time was Bernard Falk, a much respected newspaper editor. There were three Dispatch newspapers: the Daily, the Evening, and the Weekly, the last being a Sunday paper, all owned by Lord Northcliffe. Henry has written well and amusingly of this period, both as fiction in The Innocent Moon (1961; the ninth volume in the Chronicle series), and in a fascinating essay, ‘The Confessions of a Fake Merchant’, which first appeared in 1930 in an anthology called A Book of Fleet Street. In the essay Henry describes how he first approached Falk:

‘So you’re from the Chief, are you?’ he asked, looking at me doubtfully. ‘Sit down, won’t you?’

I sat down.

‘You’re going to write a column on Light Car Notes, aren’t you? The Chief sent you, didn’t he?’

‘Yes, I replied. ‘But I can write about anything.’

The confidence, the arrogance, of youth! In The Innocent Moon, Bernard Falk is called Bernard Bloom, and the Dispatch the Weekly Courier. Bloom sat in a glass-built cage inside the Courier office, which was just a single room on the third floor of Monks House – Northcliffe’s famous Carmelite House in real life – where the three papers were produced. Bloom is likened by Phillip Maddison to a jackdaw, ‘with black hair and prominent nose; although there the resemblance ended, for he had loose cheeks and altogether a loose look on his face, reminding Phillip of a clown whose melancholy reflections came with a sense of fun’.

Henry started work at the Dispatch in the second week of July 1920, on a Tuesday – as it was a Sunday paper, Sunday and Monday served as the weekend. Presumably therefore it was Tuesday, 13 July. Falk offered him a choice of remuneration: either seven guineas a week, or to go on space, the space rates being three guineas a column, or four guineas if on the article page. Henry chose to go on space – he thought, misguidedly as it turned out, that he would earn more.

There were four news reporters under the News Editor, a young man whose name in The Innocent Moon is Harry Ownsworth. Phillip’s fellow reporters were North and Singates, and a woman writer named Vivienne Lecomte. In ‘The Confessions of a Fake Merchant’ their (presumably) real names are given as Gordon West and Singleton Gates, while the woman writer is nameless, but damned as ‘the pathetic little woman reporter’.

Four reporters for a national newspaper doesn’t seem very many, but this dearth wouldn’t have been obvious to the readers of the Weekly Dispatch, for contributions from the same reporter could and did appear variously in the same issue as ‘From our own correspondent’, ‘From our special correspondent’, under his initials, under his full name – or without any credit at all. The weekly routine would be for the News Editor to cut out news items or good stories from other newspapers during the week, and send his reporters out on ‘follow-up’ stories.

They had from Tuesday to Saturday to produce the material, for Saturday morning was when the Weekly Dispatch became alive, a proper newspaper, and took over the Daily Dispatch’s news and subbing rooms. The editor, as Henry describes it, moved ‘about the building with nerve-strain making his face haggard in the electric light, while the writhing worms of paper fell from the tape-machines and the building was periodically filled with the basement roar of the rotary printing machines, and damp proofs were trodden flatter and scattered further around the feet of the sub-editors sitting in shirt-sleeves around the “subbing” table, and the reporters grew drabber and more mutinous’.

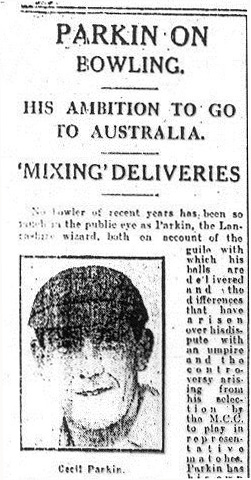

Henry relates his story well: of his scoop interview with Cecil Parkin, the Lancashire bowler, and of how this story – in The Innocent Moon at least – appeared on the front page of the early Northern edition; of going to Nottingham to interview an old woman aged 101, who had been flying in an aeroplane; of interviewing a schoolmaster in Lincolnshire, who had appeared in the Saturday Daily Dispatch, condemning the clothing of modern girls, and especially the V blouse. This particular story had been accompanied by an out-dated photograph showing the teacher with a fierce Kaiser moustache; whereas Henry found him to be a ‘mild, clean-shaven old gentleman’ with entirely reasonable views which had been distorted. Henry, having promised him that he would correct this false impression, rushed back, and was received with ‘the usual question from the editor, whose face, with its suggestiveness of a jackdaw, peered round his glass office, “What have ye got?”’ He glanced at Henry’s article, dropped it, and ‘dejected his head as he shuffled back into his cage. “You can’t write against the Daily,” his voice said plaintively. “Don’t you know the Chief owns the Daily? What else have you got?” “Old woman flies,” said Henry. “That’s better. Send it upstairs to the News editor.”’

On looking again at the teacher article, Henry realised that by taking out a few words, and adding a few negatives, it could be turned into an attack on flighty mothers. Writing ten years after the event he said: ‘Even now I am filled with shame at the thought of the dear old man, reading his Weekly, seeing himself with Kaiser moustaches, denouncing flighty mothers! I got thirty shillings for that article.’

Henry was not, it has to be said, a very good news reporter, and much better at making up stories, such as the pigeons of St Paul’s being raided by a peregrine falcon – ‘harmless stories, and easy to do’, he called them.

A more sobering story is also related in ‘The Confessions of a Fake Merchant’: ‘One Saturday afternoon the News editor said to me, “The Doncaster police have just rung up and said that a man living at Hoxton tried to cut his throat opening a mail bag after the races. He was a bookie, who had lost all his dough. Go and see his wife at this address and get a story.”’ So Henry went, and to his horror found that the man’s wife had not heard the news – ‘“What do you want to know for?”’ she asked, again and again. ‘I said her husband had met with a slight accident. There was no story in it for me. An ex-soldier trying to keep a family together by making a book; obviously an amateur, cutting open a mailbag lying under all eyes on the station. But that aspect was not news.’

However, for a reporter paid on space, his start was promising: four articles in his first week, five in his second, including his column on light cars, ‘On the Road’, for which he received two guineas weekly. His star seemed to be in the ascendant, but alas, it fell just as quickly. From August onwards, apart from ‘On the Road’, there are very few identifiable contributions by Henry. Of course, if the stories bore neither initials nor name, it is almost impossible to identify them positively, and I think we shall never know accurately the full extent of Henry’s writings in the Dispatch.

While it quickly became clear both to Henry and his employers that he was not cut out to be a news reporter, there was one small indicator of where his future would lie: he persuaded Bernard Falk to let him write a short sketch, to appear on the 4-guinea article page under the heading of ‘The Country Week’. ‘Looking back,’ Henry commented, ‘I am sure he consented out of kindness. This little feature appeared once or twice on the middle page, tucked away in one or another of the corners.’

At the time things were not going well at the Weekly Dispatch. The newspaper world was as cut-throat then as it is now, and competition fierce. Henry, in his diary, as quoted in ‘The Confessions of a Fake Merchant’, wrote: ‘16 September, 1920’ (he had been there just two months) ‘Great gloom in the W.D. office today. The paper isn’t making enough money, so economy must be rigidly enforced. The editor called us all in and said that two of us must go; he was sorry, but – I hear unofficially that I am one of the two. I do believe they think that I have independent means. Ye Gods! If only they knew. Anyhow, perhaps it’s best that I should go. The editor, whom I like more and more, says that he will take my Light Car Notes until after the Motor Show, and advises me to write fiction. Good! Now I shall begin to write.’ In The Innocent Moon the other reporter to go was named as Vivienne LeComte, described as a spinster halfway through life, who was seldom visible in the office, being on space for special woman-appeal articles. Phillip asked Bloom how the fact of two unsalaried reporters leaving would cut down expenses – it is not known whether Henry did the same.

The Motor Show was held at Olympia between November 5 and 13, but in fact Falk was perhaps more generous to Henry than he need have been, and continued to take his ‘On the Road’ column until the first Sunday of the new year of 1921. In March that year Henry left London for Devon, and his thatched cottage beneath the church in the small village of Georgeham; and in October, his first novel, The Beautiful Years, was published – his course was now set.

Let Bernard Falk have the last word on Henry’s Dispatch days. In his autobiography He Laughed in Fleet Street (1937) Henry has a paragraph to himself:

Before he began to write the nature studies, which deservedly brought him fame and praise, Henry Williamson stayed with the Dispatch for a while. Having regard to his specialised talents he was scarcely in a suitable medium, and my inability to print all his nature contributions rankled, I dare say, in his soul. If I am judged, not by what I left out, but by what I put in, then he has no cause for complaint, and the image he retains of me, if not flattering, should, at any rate, be friendly. Like himself, I was a victim of limited choice. How much rightful use of the space of a popular Sunday paper should enraptured observation of animal life command? My own fancy had a liking for the company of badgers, stoats, weasels, beavers, moles and other inhabitants of the country night, but hard news is uncompromising, and will only make room for its kind. At such times a weaver of supple and melodious prose, whose theme is the busy freedom of the humble fauna couched in the earth, falls by the way, and with bitter heart must watch the columns fill with more commonplace excitements.

*************************

Nearly fifty years later, in 1969, two young and enthusiast readers of Henry Williamson’s books, one in his late teens, the other in his early twenties, met – as much through serendipity as anything else – and had become friends because of their common interest. One was Stephen Clarke, later owner of Clearwater Books, who specialised in Henry’s first editions. He was the youngster, and lived in London. I was the other, living at the time just north of Birmingham. We were both bibliophiles, even at that tender age, and passionate about Henry’s writings. It was a magical time, with Stephen inviting me down to stay, and showing me round Lewisham, Eastern Road, Keston Ponds – all the London Chronicle haunts, while we spent long weekends exploring Williamson country in North Devon and Norfolk.

We collected Williamson’s limited editions, when we could afford them – fortunately they were very much cheaper then! – and talked of producing something ourselves. We knew of very few other people with a similar interest, so few indeed that they could be counted on one hand. We corresponded frequently, swapping news of, or newspaper articles by, Henry that one or the other of us had discovered (though it was usually Stephen), exchanging newly discovered identities of places and characters in the Chronicle – an exciting game this – and generally sought out anything and everything written by him.

And so, in due course, having come across ‘The Confessions of a Fake Merchant’, it seemed such an obvious thing to do, to ‘rediscover’ the originals of the articles that Henry had written about – we could collect them, even produce our own limited edition to circulate freely among our small circle of like-minded friends. George Harris would be sure to want one, and there was Richard Russell, and John Gillis and dear old Arthur Witham, who was then the tenant of Shallowford. Six would be enough, then. That would make it a pretty scarce item on the collectors’ market, we thought with satisfaction! But what about copyright? Ah, yes, perhaps we’d better write to Henry. Perhaps the idea would be stillborn after all. So I wrote to Mr Williamson, explaining that this was a non-profit making exercise, and asking for his permission. And, wonder of wonders, it was granted – and he wanted a copy too!

So off I went to the British Museum Newspaper Library at Colindale, and ordered the Weekly Dispatch for 1920 and 1921. I thought I knew roughly where to start – there had been enough clues in Henry’s writings. The large bound volume arrived, and I began turning the fragile pages carefully.

What were the headlines? Germany was protesting over the terms of the Armistice; the second race of the America’s Cup had been postponed because of a lack of wind – this was between Shamrock, the British yacht owned by Sir Thomas Lipton, of tea fame, and Resolution, the American yacht, which, after both yachts had won two races, eventually won an exciting deciding race; there had been a train crash, an earthquake in Los Angeles, Ireland was simmering, and the Troubles would arrive with a vengeance within months – and Air Marshal Sir Hugh Trenchard, the father of the Royal Air Force, had got married.

And then there, on the inside column of an inside page, was ‘On the Road’, signed HWW – his first column of light car notes.

And on the sports page, there too was ‘Parkin on Bowling’ as the lead feature, with Henry Williamson’s name at the bottom! 15,000 extra copies of the paper were sold in Lancashire on the strength of that interview, Henry was told by the editor.

|

|

All just as Henry had described. On to the next week’s issue, and yes – no byline this time, but there was the flying Granny, and the poor headmaster, complete with the out-of-date, stern photograph with fierce Kaiser moustache – by ‘Our Special Correspondent’ and ‘Our Own Correspondent’ respectively! I later found the first mention of the centenarian Mrs Sissons in the Daily Express for the previous Thursday, 22 July 1920, in which there was a photograph, with a caption, showing the intrepid Granny Sissons sitting proudly in the cockpit of a two-seater Avro, with a huge beam on her face. The Dispatch’s news editor had obviously seen this, sensed the possibility of a further story, and passed it on to Henry for him to follow up: and while a flying Granny might not be news today, and perhaps a rather easy target for humour, remember that commercial flying was in its early infancy then, and fatal accidents were reported in the press with alarming regularity. On the next page was the story ‘Laying A Kent Ghost’, with Henry’s initials again. Was this the first of his made-up news stories?

On the 1 August, tucked away in a corner, appeared the first of the short ‘Country Week’ articles that Henry had persuaded Falk to include.

This was all heady stuff to me. I knew that in all probability I was the first person to have seen these in forty-seven years. (Although the fact that perhaps no-one else had wanted to, or perhaps ever would want to, never occurred to me!)

The final item in the Dispatch that could positively be identified was published in the 2 January 1921 issue – the last in the ‘On the Road’ series, although by then it had even dropped its title.

The booklet of collected articles was duly completed – not as nice as I had hoped, but, financing it totally myself and committed to selling them at cost, £45 was all I could run to – it was a large sum for an articled clerk earning £3 a week!

I sent a copy to Henry, as he had asked, together with a letter floating another idea, a collection of his Eastern Daily Press articles during the Second World War (which in 1995 were published by the Henry Williamson Society as Green Fields and Pavements), and he sent a postcard, acknowledging receipt of ‘the brave little book’:

These were indeed kind words – for although at only 7 numbered copies the booklet is one of the scarcest items of Williamsoniana around, it is also almost certainly the most unattractive, the cheap card wrapper the colour of cardboard. (And note the date on the postcard: ‘Hallowe’en 1914’, with the year corrected: this was anniversary of the night that the London Scottish – the London Highlanders in How Dear is Life – first went into action at Messines ridge in 1914: was Henry there in his mind even as he wrote this?)

The Henry Williamson Society reprinted Contributions to the Weekly Dispatch for a wider audience as their very first publication, in 1983. Now re-titled On the Road – for the core of the collection is Henry’s motoring column on light cars – the Society is very happy to make it available as an e-book.

John Gregory

2013

*************************