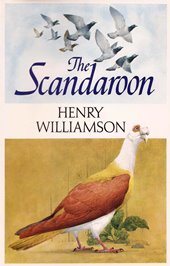

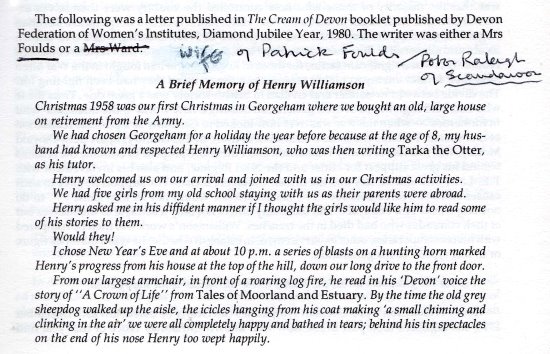

THE SCANDAROON

|

|

|

First trade edition, Macdonald, 1972 |

|

First published Macdonald, October 1972 (limited edition of 250 numbered signed copies, in slip-case) (£5.00)

First trade edition Macdonald, 20 October 1972 (£1.95) (Matthews, Henry Williamson: A Bibliography states 5,000 copies); dust wrapper and illustrations by Ken Lilly

Reprinted 1972 (2nd impression) (2,000 copies, apparently before actual publication)

Reprinted 1973 (3rd impression)

Saturday Review Press (New York), 1973 ($5.95)

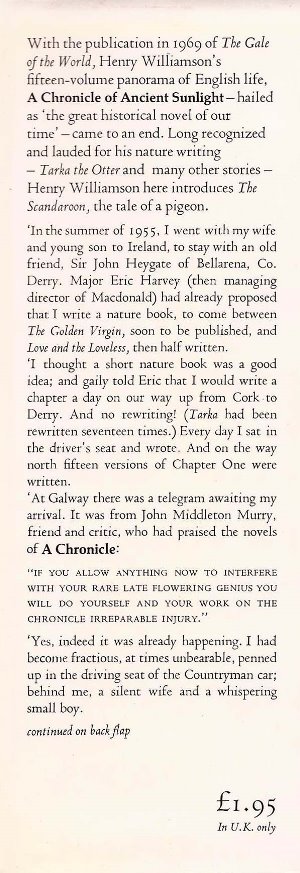

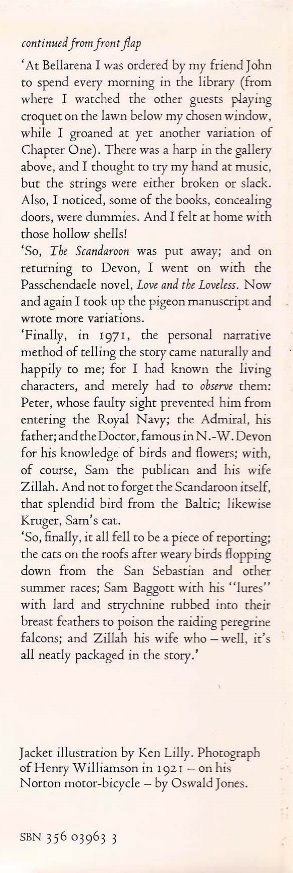

On the dust wrapper flaps HW gives a short explanatory 'Introduction' to the background of the book. This is unusual for two reasons: the flaps are customarily reserved for the publisher’s blurb and/or information about the author; and such an Introduction would customarily form a part of the book, rather than confined to the dust wrapper. It means too, of course, that this Introduction is missing from the limited edition.

The dust wrapper of the US edition reverts to the use of a blurb, which forms a useful résumé of the story itself.

HW’s Introduction:

|

|

*************************

A note on the artist:

According to an internet entry (where examples of his work can be found), Kenneth Norman Lilly (1929‒1996) was considered one of the finest British wildlife artists of his time. He was best known for his prolific work for the excellent and popular children's magazine Look and Learn, and also Treasure. There was an interesting parallel with HW’s life in that he was born in Bromley and lived in Devon. He seems to have been commissioned by Macdonald to produce the illustrations for The Scandaroon, a reflection on how times had changed: the author no longer had much influence in such matters. That there were some problems will be seen in the Background section below.

*************************

The book was dedicated to Sir John Heygate, the dedication forming a part of a fine double-page illustration:

Regular followers of HW's life and work will know that Sir John Heygate (1903‒1976, 4th Baronet) had been a familiar figure in HW's life since he first visited HW at Georgeham in 1928. The son of an Assistant Master at Eton, Heygate actually inherited his title and the Irish estate at Bellarena from his uncle, Sir Frederick Heygate (3rd Bt), who died in 1940. HW spent several summer holidays at Bellarena in the 1950s and '60s. Further details of Heygate's life and writing can be found in HWSJ 48, September 2012 (pp 57-60). He features as Piers Tofield in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight novels.

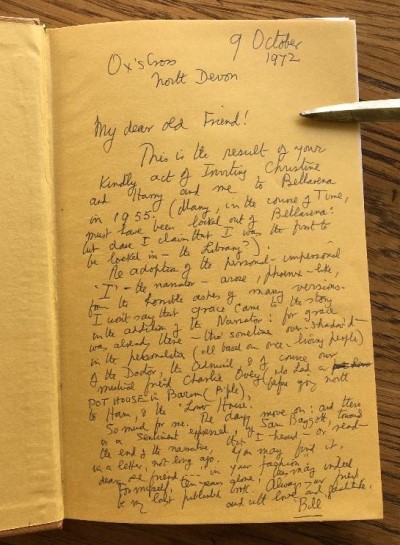

HW sent Heygate a copy of The Scandaroon on publication, inscribing it thus:

The inscription reads:

Ox’s Cross 9 October 1972

North Devon

My dear old Friend!

This is the result of your kindly act of inviting Christine and Harry and me to Bellarena in 1955 (Many, in the course of Time, must have been locked out of Bellarena: but I dare claim that I was the first to be locked in – the Library?).

The adoption of the personal-impersonal ‘I’ – the narrator – arose, phoenix-like, from the horrible ashes of many versions. I won’t say that grace came to the story in the addition of the Narrator: for grace was already there – tho' sometimes over-shadow’d – in the personalities (all based on once-living people) of the Doctor, the Admiral & of course our mutual friend Charlie Ovey (who had a POT HOUSE in Barum (B'ple), before going north to Ham, & the ‘Lower House’.

So much for me. The days move on: and there is a sentiment expressed, by Sam Baggott, towards the end of the narrative, that I heard – or read – in a letter, not long ago. You may find it, dear old friend . . . “in your fashion”. For myself, ten years alone, this may indeed be my last published book.

Always your friend and with love and gratitude,

Bill

*************************

There is nothing tangible in HW's archive to explain why he decided to write a book about racing pigeons. He tells us in his own Introductory blurb that the book had its genesis in the summer of 1955, while staying on holiday in Ireland with his friend Sir John Heygate. That is, in effect, exactly so, but as one might expect with HW, it was all a little more complicated than that.

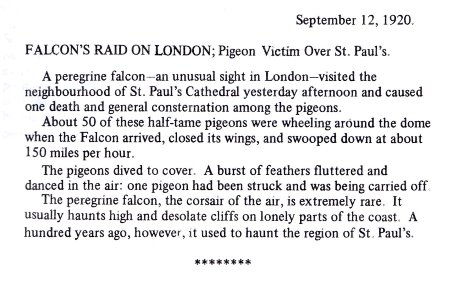

Indeed, it all goes back a lot earlier. The core of the story first appeared in written form in Goodbye West Country, published in 1937, ostensibly a diary for the year 1936 (but don't take that too literally!). The entry for 29 June is the kernel of this present tale, printed as an Appendix here. But also remember that HW had written about peregrines from his very early writing career. His book The Peregrine's Saga appeared in 1923, full of interesting peregrine 'derring-do'; while even earlier was his short item in The Weekly Dispatch, 12 September 1920:

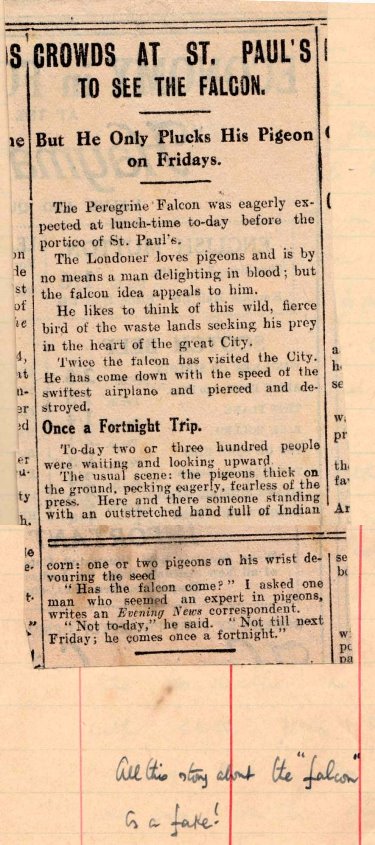

There are two other 'peregrine' cuttings pasted into his 1920s 'Richard Jefferies' Journal:

Although he states here that he had made these up, elsewhere he has denied that. Whichever is true – it shows a very early interest in peregrine falcons!

To return to 1955: there are large areas of blank pages in his diary for 1955, but what he has recorded is interesting. At the very front he had copied details of a letter he had just written to John Heygate: basically that John Middleton Murry was writing a critique essay on his (HW's) early Chronicle novels (the first four already published) for a new book – and continues with a résumé of what he was currently writing.

(At this time in his private life there was still a considerable problem arising from his wife Christine's admitted love affair with fellow teacher Alan Bowley and her continued involvement with their mutual friends in Appledore, which made HW very uneasy.)

On 5 January 1955 HW went to London to see Eric Harvey of Macdonald, his publishers, to discuss the terms of a new contract. He travelled up by train and his diary entry is worth recording. An early station the train stopped at was Filleigh, which he knew well from his Shallowford days.

The wan straying of steam when train stands in a station – blown or drifting vaguely, first one way, then hesitating, to return – and change again: just like my thoughts as we stood in the half darkness in Filleigh station: all those memories of Shallowford days.

(This too was possibly the genesis of the idea for A Clear Water Stream, which was published in June 1958.)

The next day he lunched with Eric Harvey at the Café Royal, a familiar old haunt, with Harvey described in HW's diary as:

now a Great Expenses Account moneymaker. . . .

Agreed with Harvey: 3 next novels, & one nature book, terms later. Meanwhile £300 on signing contract for Fox Under Cloak & £300 on Mss delivery.

(The fifth volume of the Chronicle, A Fox Under My Cloak, was duly published in October 1955).

A contract was signed by Eric Harvey for 'a nature book' on 28 March 1955, 'to be delivered within 15 months of date of Agreement', the advance to be: £600 payable in 12 monthly instalments of £50, commencing March 1955–Feb 1956, plus £400 on publication; and a royalty of 17½%. That was quite an extraordinary (and future problematical!) arrangement. (HW has written 'PIGEON BOOK' on the outside fold of this document, though possibly at a later date.)

The next entry is on 5 April. HW and Christine went to Oxford in his Aston Martin, where HW gave a talk to a Teachers' Conference; and on 7 April they continued on to London:

Called at a Wandsworth firm to see a new Austin A40 Countryman.

9 April: Bought Austin Countryman in morning, allowance £300 for Aston Martin. Rather sad to see last of the motorcar which had caused so much trouble. Motored back slowly in fine weather, and arrived about 11.30 pm.

This seemingly random act must have been planned – in readiness for the forthcoming (although not mentioned beforehand) holiday in Ireland which, as will be seen, was supposed to be a camping affair. The temperamental Aston was no longer viable as a family car.

As stated, most pages in his 1955 diary are blank, but HW did record that he and Christine attended a car race meeting at Silverstone on 6 May:

Arrived in Countryman at midnight. Joined silent (?) queue of sleepers in dead motorcars by the roadside.

7 May: Silverstone Races . . . Enjoyable. Italian drivers, Ferrari, all withdrew; races rather tame thereby . . .

Then totally out of the blue, with no preamble or explanation:

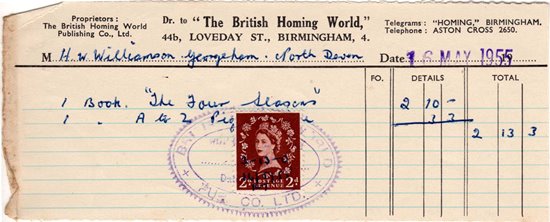

Sunday, 15 May: I sent to British Homing World, Birmingham to 2 books, one 50/-, other 3/3. P.O. £2.13.3d

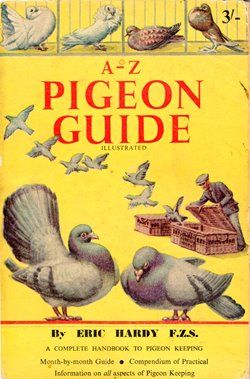

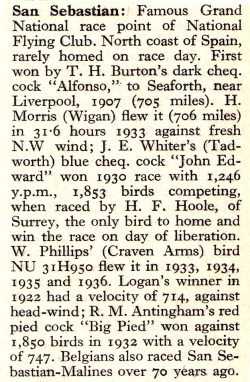

These two books were (front and back covers):

|

|

|

|

|

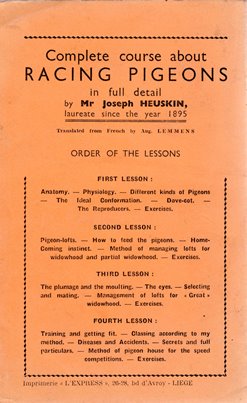

The volume costing 3s 3d, the A–Z Pigeon Guide, proved extremely useful; this is the entry for the San Sebastian race:

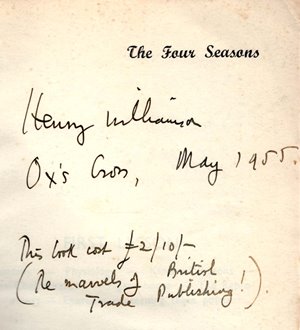

The other book, very expensive for what it was, proved of little value – being mainly full of its Belgian author's ego. HW wrote a sarcastic comment on its price in the front of it:

On 31 May HW and Christine with young five-year-old Harry (again with no previous reference in the diary) left for what was intended to be a camping holiday in Ireland. It did not go well: apart from anything else, HW's temperament was totally unsuited to such a venture!

|

|

Harry and HW in the Austin Countryman (back seat down, sleeping bags at the ready), taken at the Field prior to departure, with the Writing Hut in the background |

It was compounded from the outset by the fact that there was a rail strike in progress, which created chaos on the roads and affected shipping (as their fuel was delivered by rail!). The booked Fishguard/Dun Leoghaire crossing was cancelled, and so changed to one to Cork the following morning (involving extra expense): 'In bad temper, we carry too much clobber.'

And he admits he doesn't like camping – preferring his comfort! Arriving in Ireland, it is very wet and windy. Sunday, 5 June reveals they are moving north to Limerick to collect post at 'Post Restante'.

I brought details of the Pigeon book to write, & may start soon. What a holiday! [inevitably quarrelling with Christine.]

Adding to their problems, the windscreen suddenly cracked while they were waiting for a funeral to pass by. They stopped in a B&B – 'pleasant & safe-feeling' – while waiting for a replacement. This did not arrive until 11 June, causing much agitated irritation.

On Monday, 13 June they arrived at Galway – not collecting a telegram from Middleton Murry, as HW states in his dust wrapper Introduction, but a letter from Eric Harvey, explaining that Murry's essay on HW and his work has been turned down by Cape. With hindsight, this may just have been Cape getting one back on HW for the past problems they had had with him when they were his publisher. Murry's essay, 'The Novels of Henry Williamson', did eventually get published, being included in his Katherine Mansfield and Other Literary Studies (Constable, 1959) and later published as an e-book by the HWS. The comment that HW quotes as being from Murry had actually been made by him much earlier, when HW was proposing to start the Chronicle series with what was in effect his sequel to The Story of a Norfolk Farm.

The next day (Tuesday), now two weeks into this disastrous camping holiday, he heard from John Heygate, who invited him to Bellarena to escape the bad weather. (This may have been a telephone call.) By Thursday HW's diary proclaims his own Irish ancestry 'through Mother & her Irish father'. (I'm not quite sure how he justifies that!)

On the way to Bellarena HW stopped at the grave of W. B. Yeats, recording he did not like the great Irish poet because Yeats 'refused to allow that Wilfred Owen was a poet'. They arrived at Bellarena on Saturday evening to a warm welcome.

But HW's next diary entry, on Sunday 26 June, is long and rambling – over two pages.

I have been writing the pigeon book steadily but with difficulty – rather like quarrying hard rock with pick and bar . . . and now my peace of mind is disturbed.

A problem had arisen over Heygate, who apparently made a pass at Christine. (HW did not trust his wife since her recent love-affair.)

No atmosphere in which to struggle with a most difficult study of an almost unknown subject. . . .

The diary is then blank until:

12 July: I went down to Dublin to visit J.M. Murry & Mary M. staying with old friends [named as Lord Glenavy, Governor of the Bank of Ireland].

It is now that Murry, hearing about the proposed 'pigeon book', may well have reiterated his warning not to deviate from his writing of the Chronicle novels.

They returned to England on 20 July, recording that Heygate's wife Dora 'gave us wonderful sandwiches', enough for every meal until they actually got home! He concludes with: 'A wonderful visit' – the quarrel with John had clearly been put aside.

And, as HW relates in his Introduction, the 'pigeon book' was put away and he got on with writing the books comprising the Chronicle. However, it was not entirely abandoned, as can be seen; although the next mention of the book is in 1963. (Readers will know that meanwhile HW's personal life had been thrown into turmoil by the defection of Christine with John Fursdon.)

Several years later, in November 1963 (then living in Ilfracombe), HW undertook, in a state of great agitation and some despair, a walk on Dartmoor in a horrendous winter rain-storm. His purpose was to gain material for the climactic scene involving the Lynmouth flood, which occurs at the end of The Gale of the World – although he was still some way off writing that volume.

The day after this venture, he went up to his Field at Ox's Cross and with no reason or explanation:

I looked at Scandaroon, after some years, & found the framework professional & enough.

He then read it through to Kerstin Hegarty, his current companion.

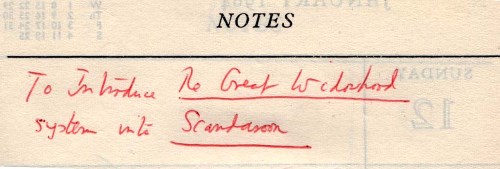

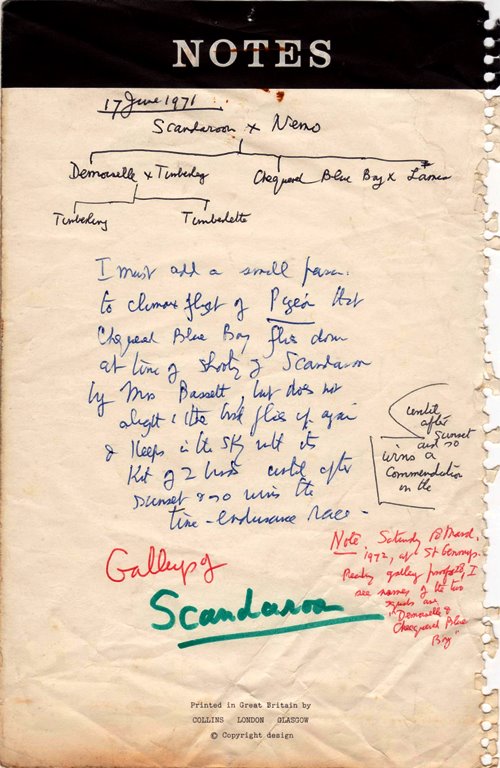

On a 'Notes' page at the front of his 1964 diary HW has written:

which he indeed did.

The next mention of the book is on 21 January 1969. The Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight is finished, and HW is in a state of emotional turmoil over the young woman known as MUS:

I have lost cohesion these days. Can't write.

Daily I say 'I'll reread Scandaroon, get to know what it's about, & end it!' And day after day it isn't looked at.

There is then the contretemps over the huge number of errors found in the proofs for The Gale of the World, which was finally published on 29 May 1969. It is obvious from the agitation of his diary entries that HW was absolutely drained emotionally at this time, due chiefly to having at last come to the end of the Chronicle series, but also longing for, and psychologically needing, female support: to some extent to look after him (cook, clean and wash etcetera), but also for companionship. After the departure of MUS there were a series of young girls, all of whom proving disastrous from his point of view.

On 10 June 1969 HW was in London:

I saw MacGibbon [his current publisher at Macdonald] in the morning . . . was keen to hear about the pigeon book. Would it be ready by 1971 for the autumn. Yes, I said . . .

22 June 1969: [in 'Notes' section] I revised last pp (done) of Pigeon. The pp were very fine – two betrothed pigeons. But how can the build-up be resolved – come to a proper climax?

Six months later, having spent Christmas with Pat and Vesta Chichester, on 29 December he wrote:

Went to Ox's Cross, made fire in Studio & Hut, determined to resume The Scandaroon. Failed.

The following day he went up to the Field again, and again failed to do any writing on the book.

30 December: I am on the down grade, unless I pull myself together.

But the New Year found him more optimistic. A note is pasted into the front of his diary:

4 January 1970: Today I force myself to resume The Scandaroon. And went to Ox's Cross & cut grass. Felt better. (Although his current love-anguish is over Anna Cash.)

5 January: . . . I've been collecting Notes for Scandaroon. I am now at start of Part Four – the last scene, of midsummer Day, & the pigeons v. falcons (or vice versa) . . .

11 January: I started more work on The Scandaroon . . . pieces taken from the first or Bellarena version of 1955.

18 January: I got on with building up past chapters of Pigeon this morning: & went for a walk around Morte Point in afternoon [with friends].

At this time HW was currently working on a proposed book on Haig, and over 24/25 January went to meet Dawyck Haig & others at Ashurst Kent. (See the page on ‘Reflections on the Death of a Field Marshal’.) He was also working on the BBC film The Vanishing Hedgerows, and finding both tasks difficult and extremely worrying. This work interrupted any work on the pigeon book, and after that burst of activity the next mention is not until the beginning of May.

But on 30 April there is a mention which bears out my 'Tolkien' thought for Sam Baggott's name (see later). He sent a copy of The Hobbit to Sue Lawrence (of whom he was very fond). HW did not personally like the book, but mentioning it on the phone to his son Robert he was told that the book was a world-wide children's cult classic. Changing Sam's surname to one with a hint of Tolkien would be typical of his thought processes.

HW also mentions here: 'I must go on with the Zig and Zag series – Scribbling Lark is long ago – written in 10 days of Xmas 1948-9.’ (This was after the problem with Christine's mother, who stopped their immediate marriage plans.) Indeed, there is a somewhat jumbled synopsis headed 'Zig & Zag' written into his appointment diary for the same date.

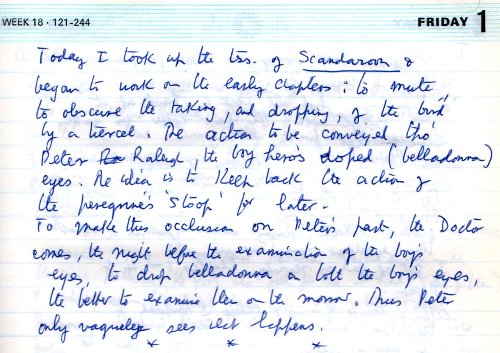

On the next day, 1 May 1970:

However all the other tasks take over, and there is again no mention until 5 November:

. . . At 12.30 pm I picked up the Tss of Scandaroon – almost complete save for a score of pages for Part 4 (the climax). 'rough Music'. And began to work on the synopsis of this final part. I wrote this entry at 2.15 pm, & even ½ hour's work has cleared my mental congestion or 'constipation'.

3 December 1970: [in London] Went to 35 Dover Street to see Cyrus Brooks my literary agent. He stressed the idea of a new contract for The Scandaroon.

That is, a new contract to replace the 1955 contract – over which he had presumably been paid the £600 in 12 monthly instalments of £50! On continuing on to Macdonald he learned that James MacGibbon, with whom he had previously dealt, had been sacked. But there are no details as to what else was discussed or arranged.

On 12 December he noted that work which continued on the 'Treatment' (for the David Cobham film The Vanishing Hedgerows), and which he found difficult to deal with and thoroughly disliked (he writes: 'Treatment' what a word!), 'has caused the ending of Scandaroon to be put off – aborted –'

And again, at the beginning of January 1971, he notes: 'No work done on Scandaroon.'

But what he did write was his essay ‘Reflections on the Death of a Field Marshal’. It is interesting to see just how much work HW was actually doing at this time, and easy to understand just how stressed he was. Despite all his problems, it was an extremely productive period.

With the essay finished, he returned to the pigeon book.

16 January 1971: Worked on final scenes of Scandaroon. The midsummer races – homers, and tipplers.

17 January: Wrote some more of Scandaroon. Little progress: all almost revision, or rather variation. . . . [continues with various items & ending] . . . MUST NOW WRITE Scandaroon. The races are on: homers from Bordeaux & tipplers in the height of the midsummer day sky.

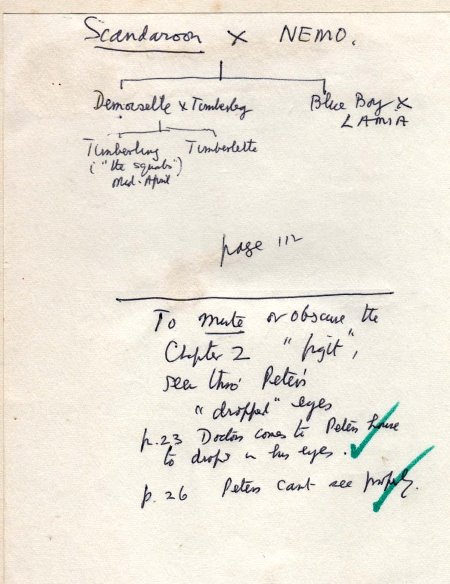

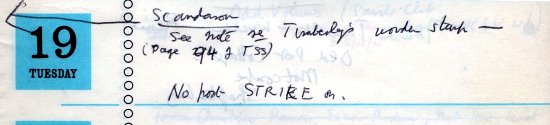

On 19 January he was still writing – the following notes are written in his Appointment Diary:

On 22 January (depressed as the mail strike continues and so he has no post – meaning, no letter from the currrent girlfriend – he recorded: 'Finished my botch-up of Scandaroon'; and the next day, 'Revised my botch of Scandaroon'; and then on 25 February: 'And continued on the VERY LAST revision of The Scandaroon.'

There was then evidently contact about the book with his agents and the publishers, which he did not record. On 26 February in the Appointments Diary is pasted a page of notes (as an aide mémoire) concerning a telephone call that HW made to Hester Green (of A. M. Heath, his agents), which covers several points, mainly that Macdonald have pointed out that all that remains of the advance for Scandaroon is the outstanding £400 on publication. (He had received £600 back in 1955 without producing the work.) HW is also worrying about a contract for the BBC film – noting he will be in London Tuesday next re film. He notes that:

I hope to bring Pigeon up with me on Tuesday. I've had it typed 5 times & the last typing by electric typewriter has about 20 pages to be retyped. Can you arrange this?

On Sunday, 28 February he made a note:

TAKE to London

1) New Forest Child

2) Revised copy of Reflections on F. Marshal

3) The Scandaroon

4) Receipt for £300 tax paid [for his accountant].

(For further information on item one, see the page for 'The New Forest Child'.)

On the following Tuesday he duly notes that he handed over the typescript of The Scandaroon to A. M. Heath. Mark Hamilton (his current contact there) told him he was concerned about Macdonald, who were very shaky, and suggested not giving them the book.

On 4 March he notes that he is worried that Scandaroon has not been handed over to Macdonald, as he has promised it and doesn't like to break his word. (And no doubt he remembered the problems of past broken contracts!) Attached to the original 1955 contract for the book is a letter from Mark Hamilton dated 17 March 1971. From this it is apparent that the typescript is now with Macdonald, who 'like it very much'. Hamilton writes:

Thank you very much for sending me the contract for this book. I have made a copy of it and here is the original for you to keep. I see they undertake to pay you a marvellous royalty on home sales, a straight 17½% which is probably better than we could do today.

After this HW was involved with filming for The Vanishing Hedgerows on his old farm in North Norfolk. On his return to London he met up with Susan Hodgart, now back as reader with Macdonald. They had luncheon together at his club. Her report on Scandaroon was not altogether favourable. She said it jerked about – not a steady narrative flow – and so HW invited her to Devon for the weekend to work on it. The next day he recorded feeling depressed:

Feel unable to be TOLD what to do over The Scandaroon revision.

Returning to Ilfracombe, he had a minor procedure at the local eye infirmary to unblock his tear ducts. Susan Hodgart duly arrived on Friday and Saturday they got to work.

Morning spent on Scandaroon. Susan is very good, and alert: she thinks and speaks too fast for me. I got confused and ground to a halt. Her notes were on 3 foolscap pp in close typing! The main criticism is that the story line wanders, breaks off and omits vital events. [Example given.]

I tried to think what to do, opposite Susan & sitting with her across the circular walnut veneered table but she spoke and I tried to grasp what to do – and where – and my mind faltered, went blank. However we cleared all to page 61, then decided to have lunch (casserole not bad) & go for a walk around Morte Hoe. . . . I felt exhausted while in the cottage.

Susan returned the next day, taking material with her to type up clean copies. She returned this work on 17 April. HW recorded in the Appointment Diary:

Susan Hodgart's astringent (better that than vague) analysis of Scandaroon arrived. Found it distressing; I back in the classroom as a small boy.

He found her notes difficult to absorb, but admitted that she had done her job thoroughly, although he found her typing difficult to read. The next day he tried to work on the book but found it 'impassible / impossible'. A week later: 'Pecked impotently at “Pigeon”. Ghastly mess. Susan Hodgart did a splendid job at fault finding but faults are too much for me.’

And the next day: 'No progress with Scandaroon. I am beaten, or feel it. Must try recover. Walked round the Morte. Felt better.’

He had to also deal with the galley proofs for ‘Reflections on the Death of a Field Marshal’. With that out of the way, in the first week of May 1971 he settled down and got on with the work, including a visit to London, where he worked in his room at his club, returning on 8 May.

10 May 1971: I am now nearing the ending of Scandaroon, & have to try to hold the detailed narrative, since a few minutes lapse of writing can bring oblivion of what I've just written – or re-re-re-re-re-written.

The following day – in both diaries:

I finished the Final version of Scandaroon after working from 11AM to 7.45PM in the garden room of 8 Britannia Row – very much relieved.

The following day he posted off pages 111 to end, for retyping.

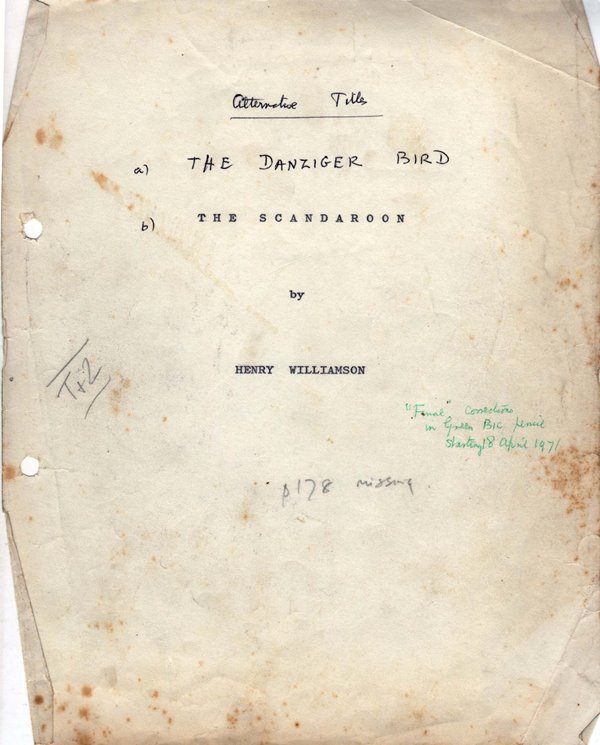

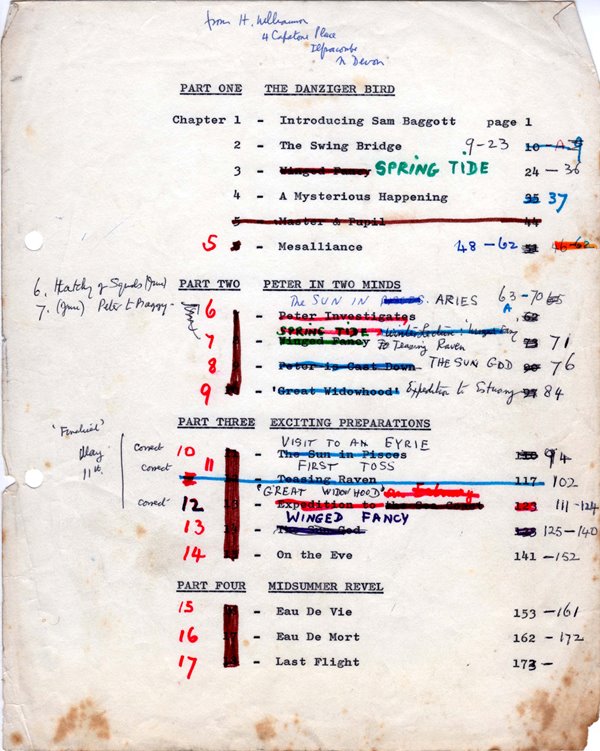

The typescript title page and revised contents:

In June 1971 he was involved with filming back on the Norfolk Farm for The Vanishing Hedgerows. On returning to London, he recorded on 16 June:

Worked in morning on FINAL draft of The Scandaroon in my bedsitter (Room 62) [he always had the same room!] at Nat. Lib. Club.

17 June: Finished Scandaroon 6.15 – 8.15 & felt relief.

There is no further mention of the book until February 1972: HW was then supposedly writing the 'treatment' for the proposed 'otter film' – a project which was actually beyond him and, after causing him a great deal of anguish, was eventually written by others. (See the page for Tarka the Otter: the film.)

On 23 February he recorded:

I was disturbed by a letter from Susan Hodgart in reference to the (wretched) proposed illustrations for The Scandaroon.

He then sent his reply and her letter on to his agents, so the actual content is unknown. But there was obviously a problem. (HW's disapproval jumps off the page!)

10 March 1972: . . . At 3.30 pm I met the illustrator of Scandaroon with Susan Hodgart at Poland St. HQ of British Printing Corporation. Susan is still keen on the two colour washed drawings of a 'falcon' slanting down at a pigeon – said 'falcon' being of the hawk tribe, with delicate snatching legs & small eyes. He has never seen a falcon apparently & Susan's continual harkening after one or t'other of the misbegotten birds etc etc made me feel uneasy. However I was as 'gracious' as one could be . . . [and continues with worried thoughts].

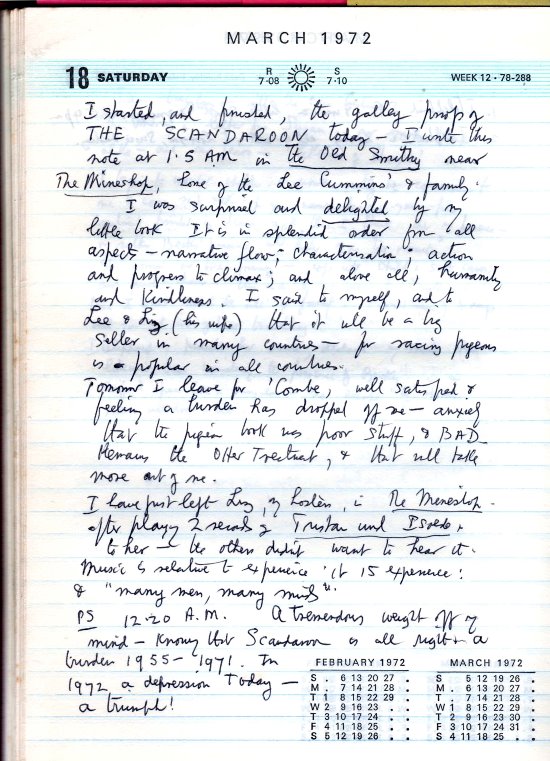

The galley proofs of the book arrived on 14 March when HW was actually in Mineshop, at the home of his typist Liz Cummins.

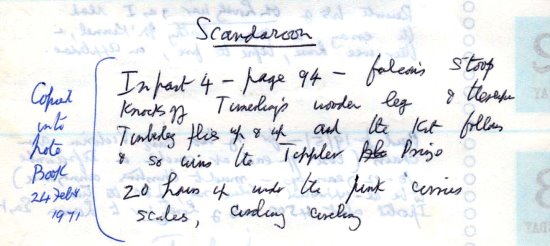

He made a further note for the galleys, which would have made a nice touch in the book, but this little piece of action was not, in the end, included:

On 9 May HW travelled to London and again met up with Susan Hodgart to see the proofs of bird illustrations for Scandaroon. 'Not bad: in fact, quite good – less a few details, such as the peregrine's stoop all wrong [actually underlined twice!] . . .'

He was in London again on the 22 May, noting that Susan Hodgart called in at the National Liberal Club with some redrawn illustrations for Scandaroon. 'They were good.'

On 14 June, again in London, this time for a run through of The Vanishing Hedgerows film, he went to Macdonald’s office in Poland Street and was given a '”jacket” for Scandaroon. I liked it, & was very pleasant.'

On 16 June he called in again for publicity photograph for the book to be taken.

Then on 15 September:

An unexpected visitor – last seen at Aspley Guise about 20 years ago, . . . Margery Boon, my childhood sweetheart – (Polly Pickering in the novels). She looked very young – hair dyed (she told me) light brown & her face was that of a young woman.

Margery was staying at a hotel in Ilfracombe, and they spent a very companionable time together over the next several days. 'We got on well together & she helped me at Ox's Cross.' It seems somehow apt that Margery should have reappeared at this point, making an alpha and omega circle.

On 18 September HW drove to Taunton (at the last minute Margery stayed in Ilfracombe), where he met up with Susan Hodgart arriving by train from London. They repaired to a hotel lounge where, surrounded by a conference of business men milling around, he signed 281 copies of limited edition sheet for The Scandaroon (i.e. 250 copies for the edition, plus 31 spares). This is the only reference to the limited edition to be found!

On 20 September he gave an interview to a Guardian reporter 'ready for Scandaroon publishing 20 October 1972' (see Critical reception for a copy of this). Margery was present, but the reporter did not grasp her significance and I suspect HW was quietly very amused. There was also an interview with Colin Wilson for Westward TV, but HW gave no details.

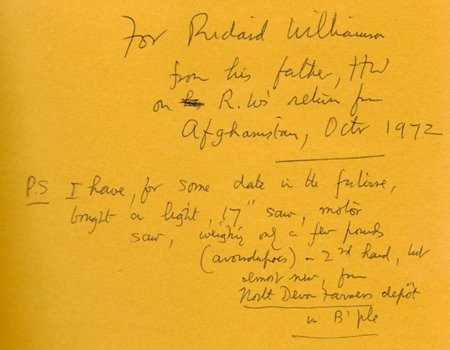

He noted sending off copies to several friends at this time, including one to us – the PS to the inscription is typical of HW!

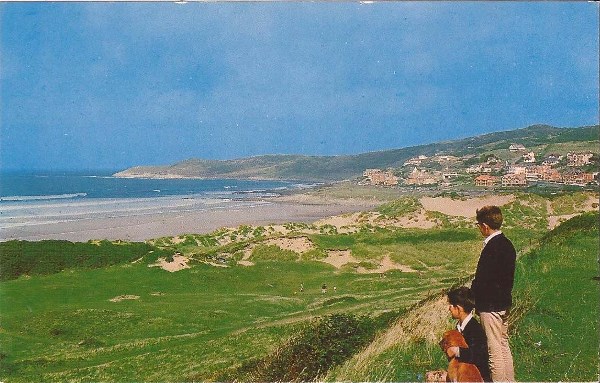

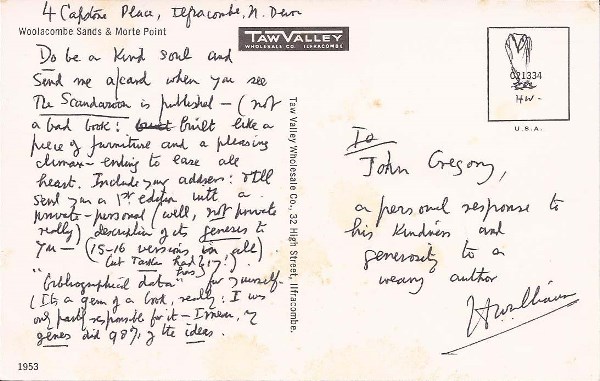

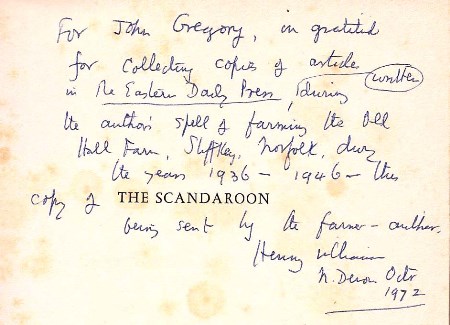

He also sent a copy to John Gregory, who earlier that year had met HW at Ilfracombe and discussed with him a project to print privately, in a small edition, a collection of HW’s articles written during the Second World War for the Eastern Daily Press. Although the project came to naught at this time (it was later resurrected as Green Fields and Pavements and published by the HWS in 1995), HW wrote to him on 25 May 1972 (note the owl instead of a stamp – the card was posted inside an envelope):

The text reads:

Do be a kind soul and send me a card when you see The Scandaroon is published — (not a bad book: built like a piece of furniture and a pleasing climax – ending to ease all heart. Include your address: & I’ll send you a 1st edition with a private-personal (well, not private really) description of its genesis to you — (15-16 versions in all, but Tarka has had 17!) "bibliographical data" for yourself. (It’s a gem of a book, really: I was only partly responsible for it – I mean my genes did 98% of the ideas.)

And in due course a copy of The Scandaroon did indeed arrrive, inscribed:

On 18 October he noted being sent copies of the Guardian item, 'quite thoroughly written'; and Smith's News, 'witty & factual'. However the actual publication of the book on 20 October is not mentioned, other than his disappointment over the review in the Daily Telegraph. He records feeling tired and despondent, and (as always when depressed) unwell. But the review coverage was really quite good.

There is no mention of the American edition in HW's personal papers. The actual date of publication is not known, but the contract was signed on 28 November 1972, and as it was merely a matter of reprinting the sheets it would have been early 1973. The book is slightly less tall than the UK edition, owing to a less generous lower margin on the printed page.

The Scandaroon was the last book that HW wrote. There is of course no sign that it had caused so much trouble in its writing. The story has a freshness of his early writing and opens a charmed window on a place and its people, giving us a view of a world that has long disappeared.

But how thrilled he would surely have been at the resurgence of the peregrine falcon in recent years. Now nearly every cathedral in Britain has its own nesting pair (Chichester, Norwich, Salisbury – to name just a few), including the church tower at Cromer and many high-rise buildings. Sightings in London and over St Paul's Cathedral are fairly commonly recorded by an enthusiastic London 'Peregrine Group', who regularly meet on roof tops around the city – no longer 'fake' news.

*************************

The tale is written in the first person singular as a reminiscence of 'time past' in 'Nry's' (HW's) life. As such it can be seen as autobiography. But of course, as usual in HW's stories, although the basic facts are biographical, there is also much that is fictional – or at least facts that are transmuted and locations that have been moved.

Set in the early 1920s, the story tells of Sam Baggott, landlord of the Black Horse Inn at Thurby in the town of Barum and his wife Zillah, who have a spiky cat named Kruger; the local Doctor, an amateur naturalist who spends most of his time looking for plants and birds; a young short-sighted lad, Peter Raleigh, motherless son of an Admiral living locally; and the involvement of all of them in different ways with the sport of pigeon racing, in particular with a somewhat odd-looking pigeon named Scandaroon – and of course, Nry.

*************************

It is probably useful to sort out the main basic real-life facts at this point – others will be found within the synopsis itself.

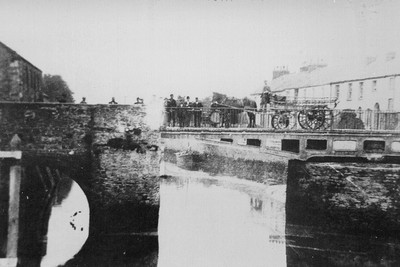

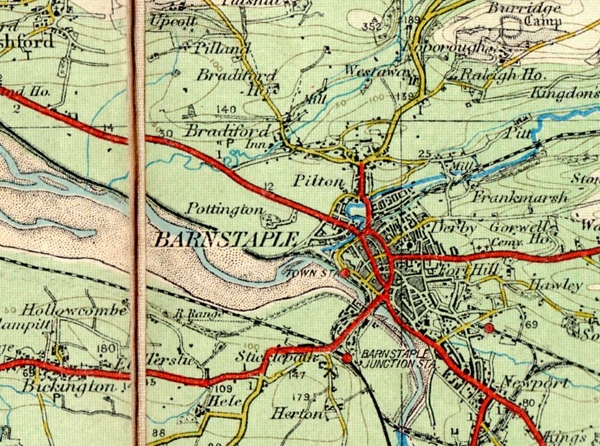

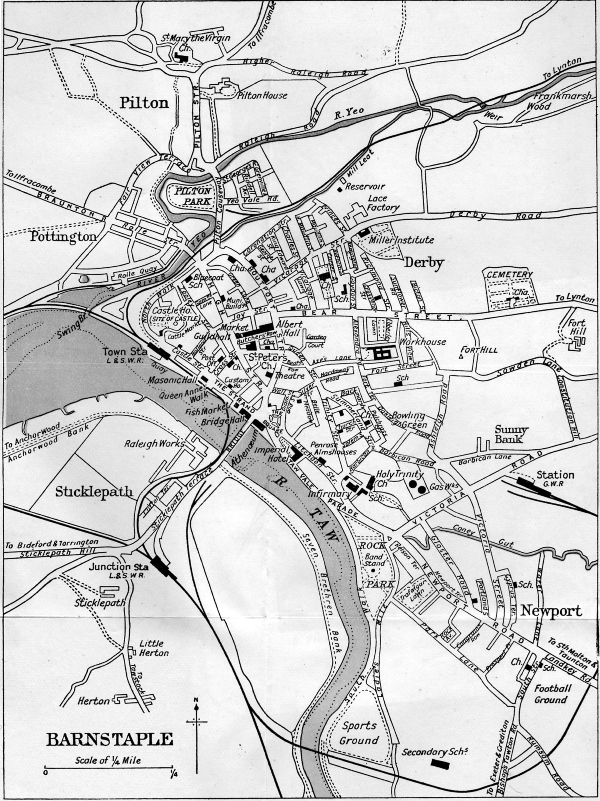

'Barum' is an old, and certainly still a local, name for Barnstaple, situated on the banks of the River Taw in Devon – in HW's 'Country of the Two Rivers' (Taw and Torridge). In the story 'Thurby' is a district of the town – and is actually an area known as Derby (pronounced ‘Durby’). The details in The Scandaroon of life in Derby at that time are all pretty accurate. The Swing Bridge was a crucial crossing of the mouth of the River Yeo where it enters the north bank of the River Taw on the west side of Barnstaple. Although no longer a 'swing bridge', the current bridge today is part of the route of the Tarka Trail.

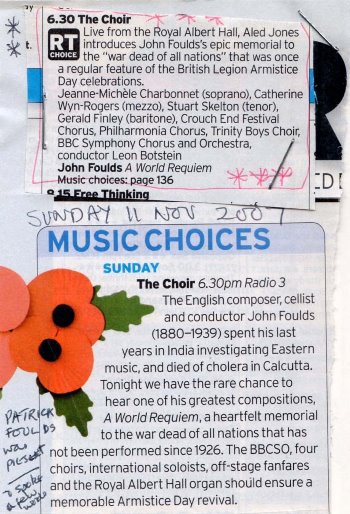

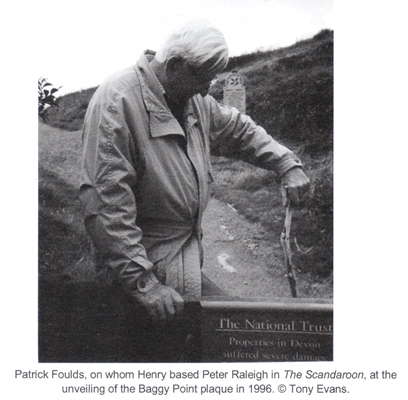

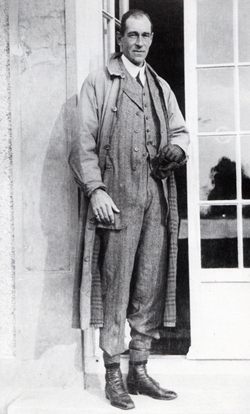

The young boy, Peter Raleigh, is the central pivot around which the story revolves. He briefly becomes the pupil, at the request of his father, the Admiral, of the author – Nry. This seemingly unlikely situation does indeed reflect real life. In the summer of 1924 HW became tutor to two young children, Patrick Foulds, then eight years old (so born in 1916), and his younger sister. Their father, John Foulds (1886–1939) was actually a composer, cellist and conductor – indeed a famous composer: his A World Requiem, an epic memorial to the war dead of all nations, was played at the annual Remembrance Day services for several years after the end of the First World War, but was not played again between 1926 and 2007, when it was broadcast on the radio in the evening of 11 November. Patrick, then over 90 years old, was present at the performance and spoke a few words which made very moving listening.

|

| John Foulds |

In 1924, the composer had to spend some time abroad in Switzerland and left the children in the care of Miss Johnson in Georgeham, the lady known for following a vegetarian regime and running what amounted to a naturist set-up. (It is interesting that this tiny rural hamlet attracted such a wide variety of eccentric personalities in that era!) HW was asked if he would tutor the boy during his father's absence. 'Tutor' is rather a loose term for HW's interpretation of his duties! He gave the boy books to read (notably Richard Jefferies’ Bevis), and took him out and about for nature rambles – but also indulged in more wild pranks such as shooting at chimney pots and using other cartridges as targets. Eventually John Foulds got to hear of this behaviour and ended the arrangement. (I think young Patrick was then sent to school in Switzerland – so near his father. His sister doesn't get mentioned!)

The only note of this pupil in HW's personal papers appears in a letter from HW's cousin, dated 24 October 1923, where she writes: 'I am glad you have two pupils. . .', but the actual name of the pupil was not known until a small item of reminiscence of Georgeham days was reprinted in HWSJ 21, March 1990.

Lois Lamplugh (who had known HW in his early Georgeham years and wrote A Shadowed Man, an exploration of his life and work) realised that it was from the wife of HW's one time pupil (see Lois Lamplugh, 'The Real Peter Raleigh', HWSJ 22, September 1990). Tony Evans (local historian and HW expert) then met Patrick Foulds in 1996, when he was erecting the plaque to HW at the entrance to Baggy Point, and has been able to add further details to the background (see particularly HWSJ 51, September 2015, pp. 21–2). Patrick attended the unveiling of the Baggy Plaque by Lady Arran, and so members of the HWS were able to meet the hero of HW's last book.

Major Patrick Foulds, RA, and his wife came back to live in Georgeham on his retirement from the army in 1958, having made a holiday visit the previous year. Contact was made with HW, and apparently he made frequent visits to their home at Incledon House, situated at the bottom of the hill that leads out of Georgeham to HW's Field at Ox's Cross. So, although there is no mention of them in his personal papers, one can see how their earlier relationship rose to the surface in HW's mind, and became a part of his tale. And as Lois Lamplugh states: '”Peter Raleigh” after those many years remembered the Henry Williamson of Skirr Cottage days with respect and affection.'

Sam Baggott and his wife Zillah – and their 'inn' – are based on Charlie Ovey and his wife, whom HW knew very well, and their pub (and HW’s local) the ‘Lower House' – properly The King's Arms – in Georgeham, which has featured in various of HW's earlier books. Charlie had been a professional boxer and of course the owner of the fox-terrier named 'Mad Mullah', who also featured in early stories. HW has merely transposed them to a fictional 'Black Horse Inn' in Barnstaple. I feel the name 'Baggott' (changed at some point from the original 'Bassett') has a most Tolkien-like feel about it. Tolkien's 3-volume The Lord of the Rings was published between 1954-5, and The Hobbit much earlier (the heroes Bilbo and Frodo share the surname of Baggins; 'Baggott' has a very similar ring to it), and during the course of writing The Scandaroon HW certainly had a copy of that earlier book, as he notes sending it to his current girl-friend.

|

|

Charlie & Mrs Ovey |

'The Doctor' in The Scandaroon is none other than HW's own doctor and friend Dr Elliston Wright (1879–1966), whose practice and home was actually in Braunton (a few miles west of Barnstaple on north side of the estuary). He started to practice there in 1906. Dr Wright was indeed an expert amateur naturalist and particularly studied the plants and insects of the famous Braunton Burrows, writing a well-known short book, Braunton: A Few Nature Notes, on the subject. In The Scandaroon his name is 'Dr Burrows' – HW's fictional names for real people are often linked in some way to the original subjects, and many readers have enjoyed trying to penetrate the disguises.

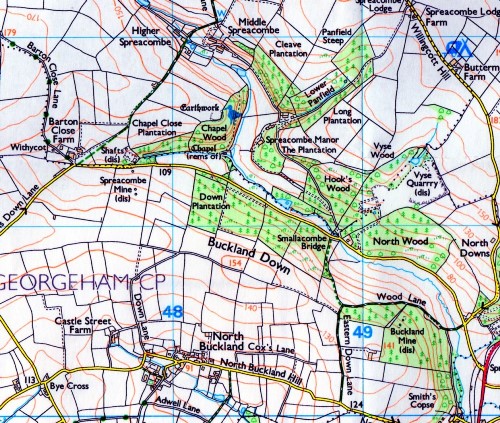

The following maps of Barnstaple show the topography of the area as it was at that time.

*************************

Returning to the actual story, the list of Contents makes a useful reference point to the structure of the book.

The story opens by looking back to when the Doctor first took the teller of the tale ('Nry') to the Black Horse Inn, situated at the back of the Town Mills, near Frobisher Quay of the sea-port of Barum. So the time is the early 1920s. At this point we are told little about the doctor other than that he had begun to practice in the town, somewhat vaguely, 'about the time when Great Britain acquired a chief interest in the Suez Canal'.

(The Suez Canal had been opened in 1869 – in 1888 it became a neutral zone with Britain the guarantor of its status. Then in 1956 there was the brief 'Suez War', and so was in the news when HW first began to formulate this book – giving this otherwise seemingly spurious piece of information a hidden connection in HW's mind! HW’s son Richard, then in the RAF, was sent overseas on active service to Cyprus, the centre of British operations for the conflict.)

We read here of the boys from the poor quarter of the town where the lace factory was situated. (Barnstaple had a substantial lace factory – see map.) These lads earning valuable pennies by acting as 'bird-runners' in the pigeon racing season: that is, running with the ring taken from the birds' legs to the headquarters of the Race Committee to have the time of return confirmed.

We are given a detailed description of the bar in the Black Horse Inn, including a strange-looking stuffed bird in a glass cage on the counter together with a 'stuffed cat with staring yellow eyes and torn ears'. Many grubby postcards are pinned up, and also a wedding photo of a tipsy bridegroom holding an umbrella over his bride. This is the proprietor Sam Baggott and his wife Zillah. Some customers tease Sam about the strange stuffed bird – a 'poog'n' (pigeon) to his intense annoyance. But he tells Nry 'That bird be the Scandoon,' and the snarling cat:

'That one be Kruger, see? I shot that one once, Nry. He belonged to me by rights, and was after the Scandoon, what I gived to Zillah. Then Zillah she shoots the Scandoon, see?'

Well, well, what could one make of that?

What one could make of it is the essence of the story which follows.

The second chapter is entitled 'The Swing Bridge'. This edifice is a focal point within the tale: the story quite literally 'swings' around it, giving a very clever architectural structure overall. We are told its history – or rather its context: here the Swing Bridge carries the main road westwards out of the sea-port town (it also carried the railway from Barnstaple to Ilfracombe, via Braunton) – while grain and timber ships from the Baltic can sail up the estuary on high spring tides, to the sawyers’ pits on one bank and the flour mills on the other. Sadly that bridge was demolished when the railway closed, but there is a 'new' bridge which is today part of the Tarka Trail.

The local men of Thurby (out of work after service on the Western Front) gather on this bridge, hoping to get work when the boats come up with the spring tides when the bridge was swung open to let them through. Nry always stops to see this event:

For it was the year in which I had come to live in my thatched cottage in a neighbouring village, after the Great War, and everything I saw was new, and indeed romantic.

The men – out of work, hungry and fearful – are rather resentful of the salmon they see coming up the river, as it is illegal for them to catch the fish. They are also owners of racing pigeons – and again resent the law that stops them killing the 'hawks' which fly over and pick off any bird they can: these 'hawks' are peregrine falcons, protected by law. We read also of the many other hazards these racing pigeons have to endure. The doctor is President of the Thurby Homing Society and Nry learns much about the pigeons and the local customs as they go on walks together.

We also learn the history of the pigeon that Sam calls 'Scandoon' – really the Scandaroon. A boat from the Baltic, a three-masted barque with a Danziger cook had come into the port. (Danzig, on the north coast of Poland, is a port that was controlled by Prussia until 1919, when the League of Nations gave it back its freedom. Today it is known as Gdansk.) The men witness the sudden appearance of a bird chased by the ship’s cook, which escapes up on to the Swing Bridge, where it is rather neatly caught by Sam Baggott – although later it manages to escape again. The men discuss the strange appearance of this bird – one like it had never been seen before in Thurby.

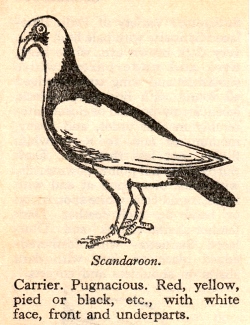

Not only was it much larger than an ordinary pigeon, but its long face and beak together made a curve like a paring hook. . . . the wings were reddish brown, the back and tail yellow, while its face was as white as a clown's. Long legs added to the odd appearance.

They call it the 'Danziger bird', after the ship and its crew. The bird is frequently seen on the roof-ridge of the Town Mills. Nry, 'sitting astride my racing Norton motor-cycle', sees it as he visits the Doctor for a check-up to get his signature for the continuance of his Army Pension. (An interesting detail – HW had a small Army Disability Pension for several years after the end of the First World War, and obviously would have needed a doctor's signature for validation.)

Sam plans to get the bird to use as a decoy to lace with poison to catch the peregrine falcon terrorising his racing pigeons. He tells the doctor the bird is a pest and needs putting down – but the Doctor knows his real reason and warns him he could get into serious trouble if he uses it to poison a peregrine. Sam moans about its peculiar looks and the Doctor tells him it is probably:

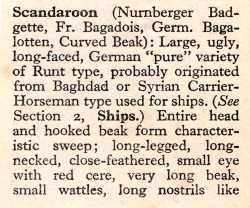

'a variant or sport of a German breed, the Nurnberger Badgette, called Scandaroon.'

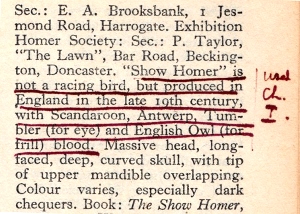

In May 1955, as has been mentioned in the Background section above, HW bought two reference books on racing pigeons. The entry for 'Scandaroon' in The A–Z Pigeon Guide provides the necessary information:

And under the entry for 'Homer', HW has noted:

Sam's cat Kruger climbs up on the roof and tries to catch this odd pigeon. It flies down and lands on a wall next to Sam's pigeon loft, and Kruger catches it there. Zillah comes out and rescues the bird and, knowing Sam's intentions, hides it in the woodshed in an old parrot cage under a sack.

Chapter 3, 'Spring Tide', opens with weather and farming details with lyrical description:

The pale green surging waters of the Two Rivers running fast and clear over rock and skillet bed . . . Sunlight and cloud-shadows race over the sandbanks left by the ebb-tide, where whimbrel and heron wade. . . .

It is now the season for pigeon owners in Thurby to exercise their old birds and to train the new entries.

The Doctor drives Nry 'in his open-bodied Mercedes-Benz' (Lois Lamplugh, in her book Georgeham (1995), states that Dr Wright usually rode a motor-cycle!) to a manor house in a valley seven miles north of town. We are not told where this is, but various clues appear to establish it as in Spreacombe (the modern spelling; variously Spraecombe and Spreycombe) – the tiny hamlet just below HW's Field at Ox's Cross – where there are old iron workings in the woods and a manor house. HW had first explored the area on that memorable holiday in May 1914 – imagining then that the workings were a silver mine!

|

| Spreacome Manor |

Here lives Admiral Sir George Raleigh, retired, with his son, an only child (the real-life John Foulds and his son Patrick). HW's use of the name 'Raleigh' is interesting. The immediate assumption is a connection with the famous naval name of Sir Walter Raleigh (born around 1552). Indeed in a convoluted way there is: when an ancestor of the locally well-known and prolific Chichester family first came to Devon he had married a 'Raleigh heiress'; and the Hibbert family (HW's first wife's family) are severally intermarried with the Chichesters. Further, 'Raleigh House' was actually a place in Barnstaple, situated just north of the Derby district (where the hospital now stands), and there is still a Raleigh Road today – so the name would have been very familiar to HW.

In the story here the Admiral has read the author's first book The Beautiful Years, and says it gave him an insight into his own motherless boy. (The novel tells the story of Willie Maddison whose mother has died in childbirth.) The Admiral asks the author if he would consider acting as temporary part-time tutor to his son if his eyesight problem means he cannot go away to the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth.

The Doctor examines Peter. He draws a sketch map of the area on which he marks the site of six different peregrine falcon eyries, one at Hartland Point, two on Lundy, another above Baggy Hole; then up the coast to Morte Point and then round to the north coast at Wooda Bay and finally on Foreland Rock just beyond Lynmouth (all places very familiar to HW readers) – all the time checking what Peter can see. The Doctor continues to talk about peregrines to the boy and so we learn a great deal of peregrine lore.

‘Peregrine falcons are lords of the air, Peter. . . . The male bird is called a tiercel [because] the hen – called the falcon – is one third larger than her mate.’

He has established that Peter has no problem seeing things close to him, and needs to give a further test to establish his long sight: to which end he puts drops of belladonna into Peter's eyes, telling the boy to come to his surgery the following morning.

The boy, eyesight blurred by the effect of the belladonna, duly makes his way on his pony 'beside the road above the estuary’, and comes to the Swing Bridge, where a ketch is berthed. The men gathered there give the familiar cry of 'Hawk up!', but Peter cannot really see what is happening, and asks if the bird which flew over him was a peregrine falcon.

'Noomye!' replied a voice. 'That be the Scandoon, midear.'

But Peter does not understand what a 'Scandoon' is, and is upset that he cannot see for himself.

The disturbance has been caused by a tiercel, recognisable to local ornithologists and the pigeon fanciers as it was partly albino, which is harrying the local pigeons, and in particular Sam Baggott's 'kit' (pack of racing pigeons), but catches the single bird – the Scandaroon. Then it drops it and starts flying erratically about the sky. Sam Baggott, excitedly watching, tells Zillah they won't have any more trouble now: 'Not from Scandoon, nor neither from th'awk!'

Meanwhile Peter has made his way to the Doctor's surgery, but Nry is already there, having his quarterly Army pension check-up. He is told that due to his outdoor life his lungs are improving. There is a commotion on the lawn outside as a pigeon falls there. The doctor picks it up and examines it – it has a ripped crop and two strips of liver tied to its breast (which the Doctor realises are laced with strychnine poison but says, 'Not a word to anyone about this').

Peter comes in and watches while the Doctor stitches the pigeon's wound, very carefully disposing of everything that has been in contact with the bird. Nry departs; the Doctor tests Peter's eyes and says he will soon be able to see clearly with help of 'gig-lamps' – by which Peter understands that a naval career is no longer possible.

The next morning Peter and his father arrive at the author's cottage (in Georgeham – a clue that the Admiral lives nearby). The Admiral explains that due to his poor eyesight Peter will now need a 'bear-leader' (a term for an itinerant, or travelling, tutor). Asked if he rides, Nry describes an amusing incident from his army training when he had to go over a jump facing backwards on the horse! (HW had received training in horsemanship at Belton Park in 1916.) But Nry asks if Peter can ride on his Brooklands Road Special 400cc Norton motor-cycle, promising to drive carefully.

Stimulated by thought of this new occupation, Nry writes 'an entire chapter of Dandelion Days' (HW's second novel) and then collects Peter on the motor-bike and they visit the Doctor. The Scandaroon is recovering and the doctor examines its eyes, explaining the various points that make a pigeon's eye so special. (All such details are contained in the A–Z Pigeon Guide that HW had bought.) When Peter asks about the name 'Scandaroon', the Doctor explains its origin – as coming from a port in the Levant once called Scandaroon, and that Dutch sailors in the early eighteenth century used to release birds to send news of their arrival at Scandaroon. (The A–Z Pigeon Guide relates this as connected with Aleppo, Syria. On my old school atlas there is marked on the coast 'Iskenderun', the nearest port to Aleppo: presumably this was anglicised as 'Scandaroon’.)

The Doctor gives the bird to Peter, together with a hen bird from his own kit – a very dark bird called 'Black Mammy'.

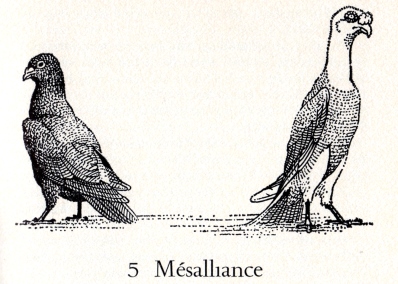

The next chapter opens with a description of Peter's home – and is headed by a Lilly drawing of the two somewhat mismatched pigeons.

Lessons consist mainly of fun games designed to stimulate the boy's imagination. The passage here is very reminiscent of Chekov's speech for Irina, 'All living things'. We also learn that HW enjoyed this period:

Despite our different ages, we were akin to one another: for all my boyhood love of country things, especially the wild birds, had returned: feelings thought to be dead during the war. I was back again in the poetry of wild life. No grown man ever had for friend so responsive a boy as Peter.

We learn Peter already has a tame raven, Kronk. He prepares a home for the new birds under the old family coach. However, when the birds arrive they do not seem very happy. A wild rock-dove appears on the scene and displays to the caged pair. There is also a peregrine in the air above. The Admiral tells Peter to let his birds out, and they go off into the trees, to Peter's acute anxiety.

Later, the pigeons all return – their behaviour showing that the Scandaroon is not male as had been thought, but that both Peter's birds are hens and reacting to the male wild rock dove. Later, while they watch the birds, a sparrowhawk swoops Black Mammy off the stable roof, 'feathers drifting down where the bird had been'.

Nry takes the upset boy off to see the Doctor. Peter tells him he knows where the sparrowhawk's nest is, but didn't want the keeper (who would have destroyed the birds) to know. Nry's own thoughts are given in a revealing explanatory sentence:

Many loyalties conflict; but – as when writing a novel of characters in conflict – it had seemed to me, ever since the Christmas Truce of 1914 in Flanders, that a writer must hold the balance between opposing ideas, and the actions springing from conflicting loyalties.

The Doctor tells them his own ideas about pigeon behaviour. The points he makes can all be found in the A–Z Pigeon Guide: HW used his source to full advantage!

Later that day Sam Baggott arrives at the Doctor's surgery, nursing a black eye where he has been hit by Zillah wielding a broom. The Doctor warns him about baiting peregrines with poison-laced pigeons. It is illegal and he will get into trouble with the law.

The story now shifts gear into Part Two: 'The Sun in Aries' (echoing the use in an earlier book of 'The Sun in Taurus').

Scandaroon and the rock dove (the A–Z Pigeon Guide explains its origin as wild ancestor of the domestic pigeon) settle down together. The Admiral decides that Peter needs a proper tutor and also that the birds need a proper loft. He doesn't want them to ruin the Jacobean coach, a precious family relic. This is to be the old cock-loft. The Doctor offers to help together with the new tutor, Mr Herbert, an ex-officer now down from Balliol. (The A–Z Pigeon Guide also has a section on how to make a pigeon loft!) Peter witnesses the love between the two birds and calls the rock dove 'Amo'. Nry writes an article for the Daily Express about the Scandaroon:

Here before me is a bird of a thousand Persian autumns, of leaves turning red as they strive to gather more of solar life before the fall, of the snow's pure whiteness on the feathers slimming the body.

And hopes he hasn't been guilty of the sin of 'anthropomorphism', quoting Hamlet's words: 'I know a hawk from a handsaw', with his own slightly convoluted explanation of the phrase. (My own understanding is that 'handsaw' was originally 'harnser' – the Danish word for a heron – which makes total sense.)

Scandaroon lays an egg and then another – Amo in attentive support. Peter thinks the birds can think, but his father refutes this, stating it is actually instinct. Peter draws on the other household pets for evidence – a spaniel which is tied up to her kennel and Kronk the raven, who steals the dog's bones and places them just beyond the dog's reach. The Admiral knocks that one back also. Peter thinks that the pigeons listen to the noises in the egg because they want the egg to hatch (as he longs for that to happen). Again the Admiral disagrees.

Peter has to leave for a lesson with his tutor. The next morning an egg has hatched. Kronk flies up to tease buzzards, but then utters a warning: 'tearing down the sky . . . fell the tiny dark barb of the albino tiercel . . . Kronk knew his tactics. He twirled over on his back, in what Mr Herbert called an Immelman turn, and held up his beak . . .' The peregrine was outwitted and went on its way.

HW writes a lyrical passage about the hatching of the eggs. Peter is thrilled to see the two tiny squabs.

And daily the sun rose like a great blazing dandelion over Exmoor, to scatter its petals, when crimson and gold, about the western sky as it went down below the rim of the ocean.

Time passes, the squabs grow. Nry, Peter and Mr Herbert go for walks in the afternoons.

Nearly a century before, Percy Bysshe Shelley, a young poet from Lynmouth, had walked the same way, to the honour of an England of the future, hearing larks in the sky, and the gentle lisp of wandering airs in the old year's heath bells, and sighing across the faded yellow discs of carline thistles.

Nothing in the world is single;

All things, by a law divine,

In one another's being mingle.

Why not I with thine?

Shelley was one of HW's mentors. The thought in those lines was echoed by another of his mentors, Francis Thompson (the phrase 'All things linkèd are' is from The Mistress of Vision). Both Shelley and Francis Thompson feature largely in the last volume of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, The Gale of the World, which had recently been published. There is some very subtle cross-referencing involved here. HW expects the discerning reader to have appreciated the overall ethos of thought.

The sun moves from Aries into Taurus (nothing so common as saying it is April or May!). Peter and Mr Herbert set off on horseback to visit the estuary of the Two Rivers, hoping to see the salmon fishermen at work. They go via the little road winding beside the estuary bank, with what is Braunton Marsh on their right – through the toll-gate (the toll charge was 6d – or 5p in ‘new’ money, quite a lot at that time), and at last reach 'the lighthouse standing on the north shore of the estuary' (this lighthouse will be very familiar to HW readers).

There is great excitement among the fishermen. Sam Baggott is there with his boat (Zillah helping) – and his final tally is 82 salmon. Peter sets himself to guard the fish, laid out in rows, from the swooping gulls, not an easy task. Sam presents him with a grilse for the Admiral. It is eaten for supper – 'luke-warm with cucumber slices in mayonnaise'. The Admiral tells Nry in confidence that he has taken in two of his farms under a bailiff from whom Peter will learn farming. (The lad is still only eight years old! But no doubt HW was thinking of his own farm that had been given up at the end of the Second World War.)

The story returns to the pigeons and the habits of Scandaroon and Amo, who now have a new clutch of eggs. Mr Herbert explains to Peter that the Latin name of Columba caligo for the rock dove means ‘bird of darkness’ – of the caves (as opposed to the tree habitat of wood pigeons).

Peter tentatively asks his tutor if he can study topography, as an excuse for going to the estuary to actually help Sam Baggott. Mr Herbert thinks this a good idea. He also wants to study in particular the very unusual Saxon Great Field

‘which lies north of the estuary, the only Communal Field of its kind left in England, the Doctor tells me.’

So they set off to the Great Field, a flat area of rich alluvial soil divided into many splatts or sections, and containing as many acres as there are days in the year.

And so HW draws into his story this remarkable area, which again has featured in earlier books.

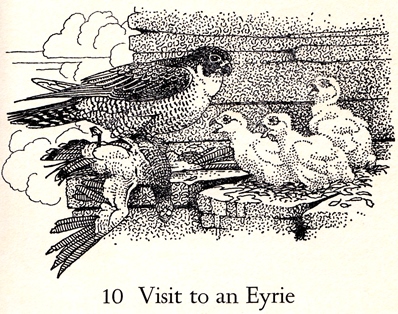

Part Three, 'Exciting Preparations', opens with 'Visit to an Eyrie'.

Nry and Peter set off on an expedition to visit Baggy Point, in particular to see the peregrine eyrie situated above Baggy Hole. The description of their route is the best evidence for placing Peter's home at Spraecombe Manor. First they pass old iron ore mining shafts – once smelted by Peter's eccentric grandfather. To the author 'it was almost a holy place'. These are relics of iron ore mining to be found in Spraecombe Woods (now a nature reserve). HW first visited these woods and discovered the 'silver' mines (as he thought then) in May 1914: that idyllic holiday just before the start of the Great War, which was to sustain him during its horrors. It was indeed for him almost a holy place.

The two walkers then climb uphill to the skyline:

On the crest was a plantation of beech and fir, standing where four lanes met – ancient tracks worn down by sled and hoof, and coursed by rains. It was my ambition, one day, to own both field and plantation.

That site is of course the Field at Ox's Cross, set on the hilltop above Spraecombe. Remember this story is set in the early 1920s: it was not until HW won the Hawthornden Prize in 1928 for Tarka the Otter that he was able to use his prize money to achieve this ambition, and where he built his Writing Hut.

Our way led down-hill again, to a village with its grey church standing above thatched cottages and elm trees.

This is Georgeham, and the church with its elm trees (later cut down) towering over HW's first home, Skirr Cottage, and where HW was eventually laid to rest in the churchyard.

They continue on their way, at first via the lane and then across country. The passage is a most lovely evocation of the area as it was then – and really still is. Here is a small extract:

Beyond the hamlet the lane rose and then sank again. Westward lay the sea, with Lundy high and clear above the line of ocean. The eastern sun lit the distant towering cliffs on a far horizon; a white lighthouse was discernible, with the farm house once used by pirates raiding ships sailing between Cornwall and the south-east of Ireland. [This is Hartland Point Lighthouse.]

Now we were over a stile and upon the first rough grazing of a headland divided by stone-banks enclosing oat and barley fields; and, far below the breaking-off of the land, lay broad yellow sands and a calm sea azure with reflected sky to the horizon – nearer, the North Atlantic was marbled lightly by currents wandering irregularly upon its surface like tracks of great invisible snails. Here was the morning of the world!

They arrive at Baggy Point:

And so we came to where the headland broadened and the furze and bramble diminished, leaving the sward ending abruptly at the precipice. . . . We walked down a path half-way around the Hole, and sat down with a view of the cave. The 310-foot cliffs were a conglomerate of iron, shale, and sandstone wind-worn and fretted into ledges where gulls were nesting.

Peter can see well with his new glasses but also has binoculars in order to examine the peregrine nest itself:

while I focus'd a little grey Zeiss monocular I had removed from a captured German gun on the Vimy Ridge in 1917.

Still, even in this last book, there is a thread of references to that war of over fifty years before, whose effect never left him.

They can see the nest, which contains three eyasses (young peregrines). Nry shouts to disturb the parent birds, which rise up, and they can see that the tiercel is not the white albino bird. There is a detailed and superb description of the birds and Peter's excited reaction:

'Their eyes have so intense a stare'. . . . ‘What a flier! . . . It's like skating!'

The falcon brings back a pigeon, dropping it from on high, and:

out shot the tiercel, to dive below the dead bird, curve up and catch it while on his back a few feet above the sea.

Peter is uneasy in case it is the Scandaroon. But on their return home, Scandaroon is happily sitting on the stable roof watching over the young squabs. Peter names them 'Demoiselle' and 'Chequered Blue Boy'. In due course the Doctor suggests it is time to start training: to 'toss' the birds up for them to find their way home. (This is recognised practice – fully described in the indispensable A–Z Pigeon Guide.) So Peter and the Admiral set off in the dog-cart, taking the 'turn-pike road' for an area of high ground known as Codden Beacon with Scandaroon and both squabs (against the Doctor's advice to take only one) in a wicker basket at their feet.

It seems rather an odd place to have chosen: quite a journey in a dog-cart. To get to Codden Hill one has to go through Barnstaple and take the Exeter road – which is indeed the old Barnstaple to Exeter Turnpike Road, established in 1829. Codden Hill is situated immediately to the east of Bishop's Tawton (where the Hall is another main Raleigh/Chichester/Hibbert stronghold).

Watching a kestrel above them, the Admiral is full of wise remarks about how Galsworthy and Turgenev would have described them – but 'Peter scarcely heard what his father was saying'! At the beacon they meet up with the Doctor on horseback. The two adults exchange further similar formal remarks.

The kestrel is mobbed by smaller birds (swallows) then another bird appears:

smaller and swifter than the kestrel, dived at one of the swallows, which flicked away under the stoop, while uttering ringing cries of alarm.

It is a merlin. The doctor reassures Peter that it won't bother his fledglings, saying the only danger is from the albino tiercel. Peter is not reassured! The Doctor says he needs to toss the young birds up – rain is coming. The birds are seen to head for home. But as the humans return so a heavy fog descends over the marshes. Peter is worried that the birds will get lost. And indeed they are not there when they get home. Peter is upset: the Admiral thinks it will teach him a lesson. The next day the birds still do not return and Peter sadly writes into his exercise book – his 'Loft Log':

Lost, believed killed in flight, Scandaroon, Demoiselle and Chequered Blue Boy.

(I would suggest that HW was here remembering his own exercise notebooks in which he kept a detailed 'Nature Diary' during his last year at school – published as 'A Boy's Nature Diary' in The Lone Swallows – and which also records details of that momentous May 1914 holiday in Georgeham.)

The next chapter is headed 'Great Widowhood'. This is actually a formal pigeon term for a process mainly used, or certainly originating from, the Belgian Pigeon Racing fraternity and is fully described in the A–Z Pigeon Guide. It is a process whereby the pigeon to be raced is separated from its mate and then teased with a brief sighting, to make it eager to return to its home – that is, it will fly faster – to copulate.

But the chapter opens with the return of Demoiselle on the second night in company with a strange pigeon. Peter entices them into his bedroom. The new bird has a broken leg. Peter takes this pair off to the Doctor, who tells him that Scandaroon and Chequered Blue Boy are also safe – they have escaped from the albino tiercel and returned to Sam Baggott's loft. He puts a splint on the new pigeon, which gets named 'Timber Leg'.

Sam Baggott gives the wandering pair back to Peter, offering any help he can give in the future. Peter takes them home and all is well. He feeds them on ground-up split peas and beans given him by Sam. A new bird arrives: Peter names it 'Lamia' (from Keats's poem on the legend of a witch transformed into a beautiful maiden to entice men), admitting that it was Mr Herbert who suggested the name.

The Doctor suggests that Timber Leg may have been a casualty from the San Sebastian race that had been flown on the day Peter had tossed his own young birds. Again described in the A–Z Pigeon Guide, this race – the 'Grand National' of pigeon racing – was flown from the north coast of Spain every year. The adults sententiously discuss the race and the 'Great Widowhood' method. Peter finds this all rather upsetting. His father dismisses this, quoting 'Nature red in tooth and claw' and other saws.

The Admiral asks our author – using his actual name 'Williamson' – for his opinion. Nry side-steps the question, but his thoughts here are of the brutal training needed to harden recruits for battle in the Great War: that 'war' motif is surfacing again.

The Admiral leaves, and after an interim passage about sundews and their peculiar habit, the Doctor then gives a more scientific opinion about the homing skills of pigeons – using magnetic lines of force. They discuss difference between 'homers' (distance racing birds) and 'tipplers' (for height and time stamina).

Peter decides he would like to race his pigeons, but can't as he is not a member of the Homing Society. The Doctor say he can join for a shilling, but to officially race he would have to have a loft within the town boundary. However, there is nothing to stop him training his birds. He decides on 'tipplers' as:

tipplers were not tortured like poor homers. Tipplers flew up and up and round and round in the height of the sky just for the joy of flying high above all the world.

The next day he asks Sam Baggott is he might rent an 'apartment' in the Black Horse loft, to train his tipplers for the 'Midsummer Revel'. (HW may be making here a hidden connection to the famous annual Barnstaple Fair, although that was held in September.) Sam agrees very readily, for he has thus, cleverly, got the Scandaroon back into his own keeping.

Ken Lilley's illustration for the next chapter heading annoyed HW, who thought it wrong for the chapter's content:

Irritated, but obviously powerless to intervene, he wrote in the margin at the top of the next page:

After dinner the Doctor prepares to give a talk with magic lantern slides. He begins with a slide of his obviously eccentric grandfather, who had been a rector in a parish in north Devon. The talk is in effect a history of the introduction of pigeon fancying. There are several references to a book by 'old Girton', the standard reference book on the subject. This somewhat heavy-handed lecture continues with interruptions from a tipsy Sam Baggott.

The Doctor then gives details of the complicated construction of a feather (again with recourse to A–Z Pigeon Guide) and then moves on to migration. The Admiral interrupts with a question: 'I take it you believe in evolution, sir?' The Doctor does – but the Admiral doesn't. The Doctor politely invites him to give a talk the following year.

The next chapter, 'On the Eve', opens with Mrs Baggott arriving at the Doctor's surgery to ask for advice on how to get divorced from Sam, who is wasting all their money on betting and drink, the latter being brandy obtained from smugglers. This bothers the Doctor, who gets his own supply of drink via Sam and the same source!

The Doctor goes to see Sam ostensibly to remonstrate with him about his behaviour – but actually to get a supply of brandy and wine! Sam states his wife had been drinking the brandy also, which is how the quarrel started – and escalated when she picked up the gun and threatened to shoot him.

The doctor notices a jar of poison behind Sam, and again warns him about such illegal practices. Sam says he has abandoned the calves liver laced with strychnine method, as it made the bird too heavy – he is going to smear the pigeon with lard mixed with rat poison instead.

The Doctor offers to buy Scandaroon for a sovereign (a lot of money to Sam), but Sam craftily says the bird belongs to Zillah, who 'dotes on thaccy bird'. Meanwhile he is preparing, as is all of Thurby, for their all-important annual race, also flown from San Sebastian. This is to take place on Midsummer Day, the day also chosen by Thurby Homing Society for the high-flying 'Tippler's Revel'.

Peter is optimistically confident. The Thurby homing pigeons are well on their way in their panniers across the channel and on to San Sebastian, escorted by two members. He is entering his two young tipplers unofficially for the Tipplers Revel, and is sure that the partnership of himself with the Doctor and Sam Baggott will ensure that all will be well.

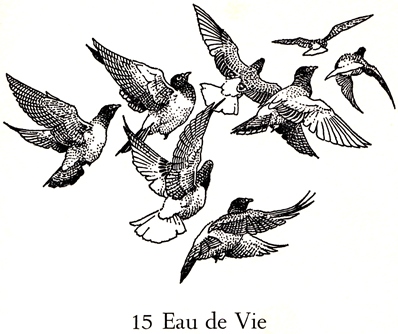

That evening the Doctor has given a dinner-party generously oiled with the liquor bought from Sam. One of the guests refers to the brandy as 'eau de vie'. This becomes the title of the next chapter as we move into Part Four: 'Midsummer Revel'.

Peter dresses and goes outside,

looking up at the sky where, remotely still and high, pale pink cirrus clouds looked like the shed breast feathers of a heavenly bird. The light of the morning star on the horizon was so beautiful, the morning so fresh! Larks were already singing high in the sky. . . .

(The morning star was very important to HW, and features in various books with varying connotations.)

He reads his notes about the rules regarding the return of the 'Homers'. Then he leaves for Sam Baggott's loft and the release of the Tipplers. When he arrives he sees Kruger standing alert on top of the wall – Zillah has attributed his long legs and staring yellow eyes to his royal breeding in Siam! The cat is harrying Timber Leg. Peter frightens it off and Sam comes out. Zillah wants to hang out her washing: Sam remonstrates as it will frighten the birds.

An umpire 'timekeeper' arrives to time the release of the birds: first Sam's birds fly out, then Peter's four young Tipplers – Demoiselle and Timber Leg, Chequered Blue Boy and Lamia. He waits for Scandaroon but the bird does not appear. Scandaroon has been shut away in the old parrot cage.

Sam goes back to bed, taking a bottle of his illicit brandy for company. As he drinks he remembers his old mates of the Cardiff docks days – killed in accidents – and his own two sons who had joined the Navy and both killed on the armoured cruiser Black Prince in June 1916 at the Battle of Jutland.

He sleeps and then goes to get more brandy, but Zillah has taken it (and given it to the Doctor). However he still has a secret hiding place in an old dressmaker's dummy – a humorous scene here to lighten the atmosphere: Shakespeare fashion. He thinks it is still morning, but Zillah tells him it is past closing time. Then from outside the 'rough noise' of '’awk over!' is heard.

The Doctor and Peter continue to look and discuss the situation. Then the Doctor, using his Zeiss binoculars, spies the albino tiercel over Codden Hill. This bird is the real menace.

Meanwhile Sam is holding the Scandaroon and spreading the poisoned lard on to its breast feathers. Outside, the local men are making 'rough music', banging tins and shouting to drive the gathering falcons away from the exhausted Homers now returning from the San Sebastian race.

Zillah suspects Sam of being up to no good, and peers through the window of the wood-shed to see what he is doing. She goes back to the house, and returns ‘this time with a double-barrelled gun. It was pointed at him. Sam knew it was loaded.’

The crowd on the Swing Bridge see the albino tiercel stoop on a pigeon –

both went down behind the red brick building of the Town Mills. There came the report of a gun: and then a scream: and, a little later, a second report.

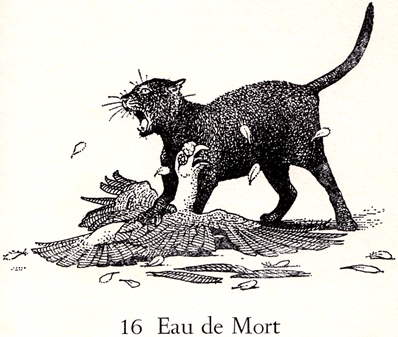

When Zillah had appeared, Sam had let Scandaroon go, in order to placate her. The bird had flown on to the wall and Zillah had pulled the trigger and shot it, hysterically screaming. Sam keeps calm, and Zillah throws down the gun. Kruger meanwhile has got to the poison-laced dead Scandaroon. Sam picks the gun up and shoots the cat, now writhing in death throes from the strychnine spread on Scandaroon.

Zillah grabs the gun and rushes out into the street, hiding it under her skirt when she meets a policeman coming to investigate. He takes the gun off her, and they return to Sam. Sam and Zillah make up:

'Yippee!' cried Sam, kissing his old darling, while tears fell from both their eyes.

The messenger boys, bearing the near-sacred aluminium leg-rings of identification to the Homing Society headquarters, ran never so swiftly as on that afternoon . . . bird after bird arriving safely home.

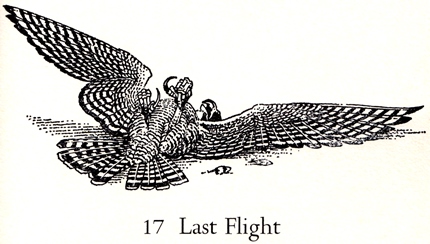

In due course the albino tiercel is shown to have an eye defect and eventually dies after catching another poisoned pigeon – its death being witnessed by the Doctor in the sandhills near the estuary of the Two Rivers.

Zillah and Sam lived on, with the two dead creatures mounted in glass cases on the bar of the Black Horse Inn, as described in the opening paragraph of the book. Nry frequently comes in for a pint and Sam relives with him the tale of the Scandaroon. Time passes. Mrs Baggott dies and is laid to rest in the churchyard (in reality, Georgeham churchyard). Sam, sad and longing for death, wants Nry to put the story of Scandaroon into a book but:

'Wait till I be gone, Nry, before writin' on Scandoon.'

And time has passed with the celandine, the daffodil, and the swallow, coming and going as the measure of our years.

A passage on the fate of peregrines follows.

The peregrine came almost to extinction during the Second World War. . . .

They were ordered to be destroyed, so they wouldn't harass and kill the homer pigeons being used to take messages from downed airmen at a time when radio silence was imperative, lest signals alert U-boats. There remained only one lone falcon in the West Country – and her behaviour was very savage, killing everything she came across.

Search and destroy may have been the order of her deprived nature, suggested Commander Peter Raleigh, DSC, RNVR, who commanded an armed motorboat in the English Channel during the war. . . .

That is one last hidden twist in HW's tale. 'Search and destroy' was of course the purpose of armed motorboats in the Second World War used for hunting down the equivalent German E-boats and other enemy shipping. We know that the real-life 'Peter' was never in the Navy (he became a major in the Royal Artillery), but by the time HW actually came to write this book he did know somebody who had indeed been the commander of an armed motorboat: none other than the naturalist Peter Scott, founder of the World Wildlife Fund. Peter Raleigh, here at the end, is Peter Scott.

HW ends his tale by telling us that the Black Horse is no longer, nor the Town Mills, and Thurby (Derby) is a welter of new building. That was 1972: today it is almost unrecognisable. But this small bit of the history of Barnstaple is preserved for ever in HW's tale of The Scandaroon.

*************************

Go to Critical reception

Go to Book covers

*************************

The core of The Scandaroon first appeared in written form in Goodbye West Country, published in 1937, ostensibly a diary for the year 1936 (but don't take that too literally!). The entry for 29 June is the kernel of this present tale, as HW acknowledges in his annotation:

*************************