THE PHASIAN BIRD

|

|

| First edition, Faber, 1948 | |

Appendices:

I. HW's notes for the writing of The Phasian Bird

First published Faber & Faber, 5 November 1948 (10s 6d)

(At some later point, date unknown but probably after two years, the price was dropped to 5s.)

Little Brown and Company (Boston, US), An Atlantic Monthly Press Book, new edition, October 1950 ($4.00)

The edition had different preliminaries, while the text was considerably revised: see Appendix II for an explanation and analysis of the variations.

The Boydell Press (County Library Series), paperback reprint of UK first edition, 1984 (£4.95)

The Phasian Bird combines the story of life during the Second World War on a near-derelict farm on the Norfolk Coast (the 'Norfolk Farm') taken over by Wilbo, an artist, with that of a Reeves' pheasant – an exotic species of pheasant with a tail of up to six feet, or nearly two metres long – here named Chee-Kai, the name given to it by the Chinese (meaning 'Arrow Bird', but perhaps also reflecting its rather sweet call, so different from the harsh grating of the common pheasant). Wildlife on and around the farm is described in detail and skilfully interwoven with the human characters who live and work there: the farm labourers, local poachers and American soldiers billeted at a nearby camp. The book ends with the (symbolic) death of both Wilbo and Chee-Kai from senseless greed and ignorance of poachers and soldiers in a classic HW description of dramatic death at a time of prolonged severe and intense frost.

You will read here the story of life on the farm as the sun would have seen it, with all the minutiae of life, human and nature, spread out on the canvas: equal weight given to each stroke of the brush, for it is a great painting in words. The full scenery of life is portrayed, very muted, very understated, and so all the more powerful. HW draws on memory of the tiniest detail and events, and with his writer's skill embellishes each incident with understated drama. The structure and timing of events, the building up of tension, all superbly captures the unfolding of the plot.

Although The Phasian Bird is less known than his earlier important duo of nature books (Tarka the Otter and Salar the Salmon), it has the same power and artistry as they do, and surely completes an important trio of animal biographies: first, of an animal, then a fish, and now of a bird, The Phasian Bird. (With a little mental adjustment one can say: earth, water, air: the three elements.)

The genesis of this book is obvious. HW's life on the farm, with its struggle and trauma combined with that of the Second World War, needed a vehicle to act as allegory. He would have known that the keeper of a near-by shoot at Hindringham, three miles from Stiffkey, around the time that he himself took over the Norfolk Farm, had bought in a clutch of Reeves' pheasant eggs and managed to rear just one to maturity. The magnificent bird became an emblem, and the keeper would not allow it to be shot. But eventually, inevitably, during a noisy and lively 'battue' the bird took fright, rose higher and higher and disappeared – in the direction of Stiffkey. Although the Hindringham keeper looked for it everywhere in the area, it was never seen again. (It should be noted that HW himself did not actually have either a true bred or a hybrid Reeves' pheasant on the farm.)

Chee-kai, as a Reeves' pheasant, is a stranger, a 'furriner' (Norfolk for foreigner) in a hostile land, just as Wilbo is also an incomer – stranger – furriner – in a hostile land. As indeed HW himself was. At that time, living in virtually closed communities, Norfolk folk were renowned for their hostility to strangers. It is also wartime, with all its connotations, and the backdrop of war permeates the book like a fever that cannot be shaken off.

Apart from the obvious allegory as above, the Phasian Bird is also a fire-bird – a phoenix: its fate is to die, but it will rise again. Thus it is akin to The Gold Falcon – and Wilbo is, in spirit at least, akin to Manfred. This metaphor also applies to HW himself. He had come to the end of an era so, as Wilbo, he kills himself off – ready to rise and start again.

It becomes evident, as one absorbs all the facts that emerge in the following discourse, that HW had many problems when writing this book. Most of this was due to the fact that he had an enormous amount of material – in his mind and in actuality – and changed his mind several times on what to include and what discard. Hence, as will be seen, his request for so many copies of galley proofs at an amazingly early stage – from which he could make numerous versions.

It is also obvious that it is a book he had to write – to get the Norfolk Farm out of his system. His psyche was overfull with the sequel to The Story of a Norfolk Farm. Thwarted at publishing that sequel, he put everything into The Phasian Bird. Only when he was clear of that whole experience could he go about writing that long-delayed series – the dream of his adult life – A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight.

The book could not have been written by someone who had not experienced at first hand life on such a farm and the countryside. Neither could it have been written by a word-smith with a lesser skill. Indeed, such a book could only have been written by HW.

*************************

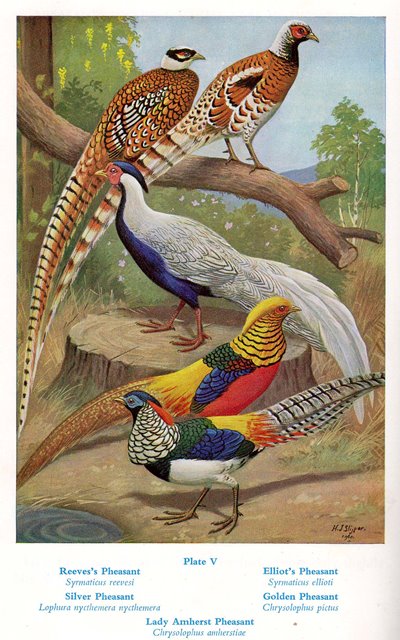

The Latin name 'phasian' for pheasant comes from the habitat around the River Phasis in Colchis in ancient Asia Minor – Kolkhis on the Black Sea – home of the Caucasian pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), which, with its several variations, is very common in this country, being bred for shooting together with the Chinese Ring-neck (Phasianus colchicus torquatus). One of the books that HW used for reference was W. B. Tegetmeier's Pheasants (1888), which contains a striking engraving of a Reeves' Pheasant. After completing the writing of The Phasian Bird he gave the book to his 12-year-old son Richard for Christmas.

A Reeves' Pheasant (Phasianus reevesii) is actually a true species and not a hybrid, but does interbreed with common pheasants, although any female hybrid birds are not fertile. It is much larger than an ordinary game pheasant and, although it prefers to skulk on the ground in cover, it is a very strong and high flyer. It is also a very aggressive bird. The original habitat of the Reeves species is the forested uplands of China, the bird being first introduced to this country in 1831 by a Mr Reeves. (By coincidence, I am personally acquainted with the species, for in the late 1960s/early 1970s I successfully bred them, together with other rare pheasant species, for Edward James, poet and patron of surrealism.)

|

|

Illustration by H. J. Slijper, taken from H. A. Gerrits, Pheasants (1961) |

The painting made by Mildred Eldridge for the cover is very exact, showing the tail spread as a brake as it either turns or prepares to land. Mildred Eldridge, RWS (1909‒1991) trained at the Royal College of Art under William Rothenstein and also in Rome, winning the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1934. In 1940 she married the distinguished Welsh poet and Anglican Priest, R. S. Thomas (1913‒2000). Interestingly, in the mid-1930s she was part of the celebrated group of four women that executed murals in what is now the Prendergast School (originally the West Kent Grammar School) on Hilly Fields, opposite HW's family home at 11 Eastern Road, Brockley. (The panel executed by another member of this group, Evelyn Dunbar, depicts Hilly Fields itself and includes two small boys searching in hedgerow for birds' nests – one of which surely represents young Harry (HW's boyhood name) and perhaps the other is his boyhood friend Terence Tetley: 'Desmond Neville' in the Chronicle.) In the late 1940s contact with Mildred Eldridge was made by Faber. She drew the sensitive and evocative illustrations for the new and heavily revised edition of The Star-born (Faber, 1948). Then when Faber also asked her to provide the cover for The Phasian Bird she painted the superb picture of a Reeves pheasant in full flight, capturing its wild strength. The final painting differs in detail from her draft for the cover, which is reproduced below – note her suggested pencilled positioning of the title and author: rather better, one feels, than the white 'labels' obscuring her painting on the dust wrapper:

The title page quotation, 'The letter killeth', is from Corinthians II, Ch.3, v. 5:

. . . our sufficiency is of God; who also hath made us ministers of the new testament; not of the letter, but of the spirit: for the letter killeth, but the spirit giveth life.

Although this seems a little obscure, that the Epistle to the Corinthians had particular significance for HW becomes noticeable within the later Chronicle novels, where he frequently evokes the well-known 'Charity' collect – equating it with 'clarity'. I think that perhaps, as so often, HW is playing with the reader – expecting them to know the source of the quotation; and so the emphasis should be on the phrase not quoted: 'the spirit giveth life'.

The book also has an acknowledgement: I have not fathomed this mystery out and any suggestions would be most welcome!

*************************

It is probably useful here to give a brief résumé of HW's life at this point, as the last literary 'biographical' contact was via The Story of a Norfolk Farm, which ends as the Second World War breaks out. The war years on the farm are not covered until Lucifer before Sunrise (vol. 14 of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, 1967). While East Anglian readers would have been following HW's progress through his various articles in the local newspaper, the Eastern Daily Press, his general readership would have been left in the dark.

HW sold the Norfolk Farm at Michaelmas 1945, and (although HW and his wife had decided to part) he and the family moved into Bank House, Botesdale (near Diss on the Norfolk/Suffolk border), at the end of October 1945. HW took over what had once been the servants’ quarters, approached by their own 'back stairs'. Over that winter he worked on the sequel about life on the farm. This was sent off for typing on 17 July 1946. It is this typescript (much revised!) that eventually, after various complications, became the basis of Lucifer before Sunrise.

While at Botesdale HW met the famous racing driver St John (Jock) Horsfall, who lived nearby. He was currently preparing his 2-litre 'Ulster' Aston Martin for the Belgian Grand Prix, and tested the car on the road that passed through Botesdale, to the great delight of HW's ten-year-old son Richard, the other children being away at boarding school. He used the garage that was near Bank House. So – seeing an advertisement for a 1938 2-litre Aston Martin (DYY 264) for sale nearby by a Dr Vicenzi for £800, HW bought it. It was almost immediately out of action and in the local garage. (The subsequent 'French-farce' problems with this superb status-symbol car need their own story!)

Loetitia's brother, Robin Hibbert, and his wife Betty also took up residence at Bank House as Robin's war-time job ended. In due course they emigrated to Australia. Also resident as lodgers for a while were a Wing Commander Vivien Bridges (ex-Pathfinder in Bomber Command flying Mosquitoes, currently stationed at nearby Bury St Edmunds) and his wife.

In the summer of 1946 HW renewed contact with Malcolm Elwin, who had taken on the editorship of the West Country Magazine, and who asked for a contribution for the first number. HW now met Elwin's 16-year-old step-daughter Susan Connelly – and fell as precipitously in love with her as he had with Ann Edmonds ('Barleybright') in 1933. (Susan becomes 'Miranda' in The Gale of the World, the final volume of the Chronicle.)

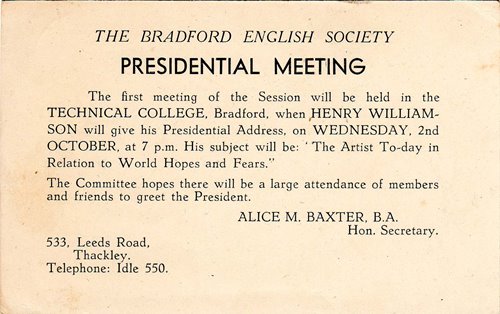

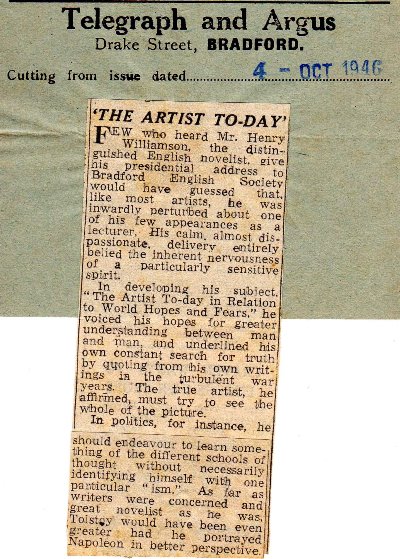

During 1946 HW visited the Sutcliffes (the couple who rescued him from what seems to have been a suicide attempt on Putsborough beach in 1945) at their home in Wakefield, Yorkshire, several times. On one of these he gave his 'Hamlet and Modern Life' lecture at nearby Bradford on 29 September 1946, at the invitation of a young John Braine (yet to make his name as a novelist: his first book, Room at the Top, was not published until 1957), while a few days later he gave his Presidential Address to the Bradford English Society on ‘The Artist To-day’, which was reported in the local press. Frustratingly, there is nothing in the Archive that sheds further light on his involvement with this society.

HW now instigated the previously agreed divorce proceedings, and so had to remove himself from the marital home at Botesdale. He arranged to lodge with his good friends Mike and Margery Mitchell (another couple rarely mentioned!) at their cottage in Georgeham. He arrived there on 11 October 1946. The day before leaving Botesdale he gave his Alvis Silver Eagle to Ann Edmonds, now an ex-ATA (Air Transport Auxiliary) pilot and glider expert, for her to use as a tow in her gliding business. HW had met her father by chance when recently in London on business – and contact had been renewed.

On his way down to Devon HW visited his father, dying in a nursing home after a prostate operation. HW was upset by his father's circumstances, but his sister Kathy was nominally in charge of things and brooked no interference. William Leopold died 31 October 1946. (There followed considerable family disagreement about his Will.)

On arrival in Devon, in bed recovering from the immediate events, HW wrote an optimistic note (within his current exercise notebook) summing up life at that moment.

This is followed by a plan of action regarding writing and eating: both to be regulated (and both soon broken)! And he noted:

By Christmas I shall have cleaned up The Journal of a Farmer and be on with the Pheasant Book.

This is the first actual mention of the book.

He was however temporarily distraught, as his love for Susan was thwarted. This is all recorded at agonised length in two exercise books. The problem (for HW) was that the Elwins (mainly Eve, Malcolm's wife and Susan's mother) had no intention that their young daughter should become involved with him. This family problem did not, however, stop Malcolm Elwin from providing huge support to HW over the writing and publication of the Chronicle in due course. Indeed, as reader for Macdonald he was responsible for the series being accepted.

The winter of 1946/7 was particularly severe, beginning in December but really setting in from mid-January, until a sudden thaw on 10 March caused widespread flooding. With the country still in the throes of war shortages, particularly of coal, and with rationing of food still in place, crops countrywide were frozen into the ground under several feet of snow, causing great additional hardship to both farmers and the whole population. This has bearing on HW's thoughts for the pheasant book, which opens and ends at a time of great frost. And although HW had experienced similar (but not quite so severe) conditions on the farm over at least two winters, he is also using the extraordinary ice-storm that occurred in an earlier year for his descriptions for the finale. (It must surely also have been a great personal relief that he was no longer a farmer.)

The decree nisi for the divorce was obtained on 14 July 1947. In late September Ann Thomas returned to work as HW's 'secretary', and once again her neat entries in the diary of work done reveal details of daily life.

On 10 October HW and Ann travelled to Botesdale and the next day went on up to North Norfolk to stay with his friends of the farm days, Major and Mrs Hollingsworth, known as Holly and Mossy, to whom he dedicated the American edition of The Phasian Bird (see Appendix II). As far as I can be sure, this is the very first mention of them in HW's archive. Although not stated, this visit must have concerned research for the pheasant book. Ann noted in the diary that while there HW 'Bought 4 Cox's apple trees for the field.'

They returned to Botesdale on Tuesday, 14 October, where they stayed a week, Ann recording merely for each day: 'At Botesdale'. HW must surely have been working on the book at this point.

On 21 October they drove (in the Ford, the Aston still being in dock) to Malvern, where Ann had her own cottage. The following day HW gave a lecture at St Michael's College, a choir school at Tenbury, which his young son Richard now attended, and where his friend Eddie Pine now taught. (Eddie, a Classicist, had earlier taught at Westminster Choir School, which John, another of HW's sons, had attended, until leaving for Paston's, the prestigious school in Norfolk.) The diary notes HW was paid £5-5-0 for the lecture! The following day HW and Ann travelled on down to Devon.

On 4 November the pair travelled to London where HW met with a film producer from Random Films about a proposed film of Tarka the Otter. HW was very involved on the work for that over a considerable period of time; but it came to nothing. While in London he also saw Arthur Calder-Marshall about a broadcast for later that month. They travelled on to Botesdale on 6 November, again no details. (One may deduce that HW's Writing Hut in the Field at Georgeham was not fit for living and working in during the winter months: the large Botesdale house with all the children away at school was far more suitable!)

On 14 November they travelled to London. HW met with an official from the C.O.I. (Central Office of Information) to discuss a commentary for a documentary film, and this involved further work, with visits to view the film etcetera. In due course this is revealed as a film on the previous winter's severe weather and its result on farming: 'Trial by Weather', for which the following February HW was paid £50. Sadly there is no copy of this script in the archive.

It was at this time that HW became aware of the poetry of James Farrar, the young pilot killed in action: poems were published in The Adelphi by John Middleton Murry, and he wrote to the poet's mother on 19 November 1947. (See the entry for The Unreturning Spring.)

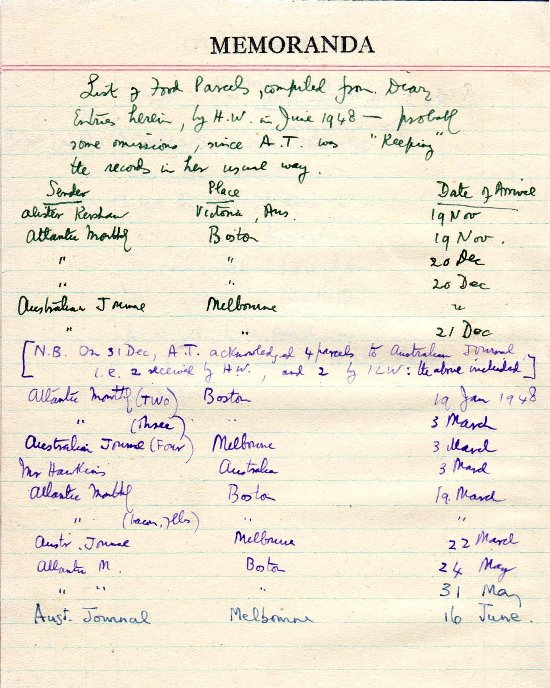

Also at this time the diary records several 'Food Parcels' received. This was an extraordinary arrangement with his US publishers, put in place because of government regulations on the movement of money, due to post-war constrictions. These food parcels were sent in lieu of royalty payments! They seem to have consisted of bags of rice, dried fruit, tins of fruit and similar goods. Ann also made a list of these in the 'Memoranda' section at the end of 1947 diary (probably for Income Tax returns!).

In the diary entry for Thursday, 20 November there is at last actual mention of the book itself:

HW wrote 700-800 words of “Phasian”.

And the following day:

HW working hard on “Phasian”.

He also prepared an article from his 'Lucifer' material, 'A Chronicle Writ in Darkness', for The Adelphi. He sent this to Atlantic Monthly too, but it doesn't appear to have been published.

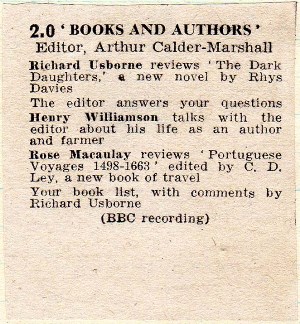

On 24 November HW was again in London to see someone from World Wide Pictures about the proposed Tarka film and also to record the programme with Arthur Calder-Marshall for 'Books and Authors', which was broadcast on Saturday, 29 November 1947.

On 17 December HW wrote to Sir Stephen Renshaw asking if in the '30s there were any signs of hybrid Reeves' pheasants at Merton and if they crow and flap their wings as ordinary pheasant (meaning that while a true Reeves does not exhibit this behaviour a hybrid might).

(Sir Stephen Renshaw was the father of Margot: they are respectively 'Lord Abeline' and 'Melissa' in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight.)

HW also dealt with the proofs of 'Some Pets on Our Farm', written for Tribute to Walter de la Mare, on his 75th Birthday' (Faber, 1948).

On 22 December HW and Ann left for Botesdale, spending a night at Newbury (home of Ann's mother) and another at Chertsey with Mary Hewitt (née Hibbert, a cousin of Loetitia and her bridesmaid, with whom HW kept in close touch), collecting HW's daughter Margaret (now 17¾) and arriving at Botesdale at 6 p.m. on Christmas Eve.

On 2 January 1948 Ann went back to Devon to collect Lucifer MS, returning the next day. HW contacted Lady Downe and on 11 January went again to stay with the Hollingsworths at Langham (on the North Norfolk coast); the following day AT noted:

HW borrowed Vol. III William Beebe's Monograph on Pheasants from Lady Downe.

This is William Beebe (1877‒1962), esteemed American naturalist, writer of 21 books and over 800 articles, who undertook a 'pheasant expedition' in 1910, visiting the Himalayas, Borneo, China and Japan. He was away for 17 months. The resulting book, A Monograph of the Pheasants, was published in four volumes between 1918 and 1922 (a delay in publication had occurred as, due to the complicated colour illustrations, the book was being printed in Germany when the First World War broke out). HW must have seen this rare volume at Lady Downe's on one of his pre-war visits. HW had known about William Beebe (not to be confused with 'BB', who was Denis Watkins Pitchford, a prolific and popular natural history writer) since 1925, when Constant Huntingdon (of Putnam's) gave him a copy of Beebe's Jungle Days (Putnam, US, 1925), which has a most beautiful cover and end-paper design by Isobel Cooper. The book relates stories of Beebe's time in the jungle of British Guiana.

The book is a fascinating collection of facts and often wry observations – but Beebe was not a 'writer' (when compared, for example, with W. H. Hudson, who was!).

A lot of business is recorded during January: mainly HW meeting his accountants and officials about his Income Tax at nearby Bury St Edmunds, which seems particularly complicated and worrying. This actually concerned the sale of the farm, and involved making returns for the whole of the time that he owned it. There is no mention of the book until 29 January when Ann went ‘To London, taking 3 typed copies Parts 1 & 2 Phasian Bird’. (HW had gone down the day before.)

Then on Friday, 30 January HW ‘took 2 copies of Parts I & II to Cyrus Brooks [his literary agent at A. M. Heath] & 1 copy to de la Mare (Faber's)’.

On 6 February HW again went to London: 'to see publisher about Phasian’.

13 February: Part III (pp 147-236) of PHASIAN BIRD sent to R de la Mare, Much Hadham [his home address]. Also by air to Bernice Baumgarten, Brandt & Brandt [New York: US agents] mentioning cable from Atlantic Monthly Press [some time back they had expressed interest in HW's new book].

14 February: Sent to Cyrus Brooks Part III Phasian with covering letter.

Interestingly, on this day Ann's diary note reveals that HW, in response to a letter from the publishers, agreed that Tarka should in future be published by Puffin, the children’s imprint of Penguin, instead of the Penguin imprint.

On 17 February AT wrote to Faber asking that 15 copies of the galleys of Phasian should be sent. That is unusually excessive – and of course never happened, although some extra copies were provided.

20 February: HW finished “The Phasian Bird”.

22 February: [Letter] To Dick [de la Mare] asking for £1000 advance -- £500 on publication.

25 February: Part IV (final) of PHASIAN BIRD sent by airmail to Brandt & Brandt, & to R. de la Mare, & Cyrus Brooks. (pp. 237-365)

HW and Ann left Botesdale for Devon on Monday, 1 March, staying the night with Ann's mother at her Starwell Farm address.

3 March: Long letter from Dick re Phasian.

This was answered on 7 March, as the diary notes:

To R de la Mare re altering Phasian in proof & agreeing to have £250 for “Fergaunt” deducted from advance of Phasian.

[Faber had paid an advance of £250 for a proposed book, 'Fergaunt the Fox', on 1 Jan 1936. The book never materialised.]

It is interesting to note here that on 13 March HW wrote to Benjamin Britten, the composer, at Aldeburgh about the proposed Tarka film, sending a copy of the book. There are no further details available – but presumably the suggestion would have been that Britten should write the score. Richard Williamson remembers that HW had attended a concert by Britten and Peter Pears at Bury St Edmunds while at Botesdale (the same night that young Richard had listened to a broadcast of The Dark Tower on the radio – music also by Benjamin Britten). There is a 1947 letter from Britten in the archive (now at Exeter University), which I had previously thought referred to The Phasian Bird, but which clearly now is to do with this Tarka proposal.

16 March: HW wrote to Malcolm Elwin asking if he would like to read and comment on “Phasian” and also to Mac Hastings.

(This is Macdonald Hastings, who in 1943 had attended a farm shoot, accompanied by a professional photographer, and which event filled several pages of Picture Post in its issue of 6 November 1943. This event is recorded in detail by John Gregory in the excellent article 'Journalism: The Public Face of the Norfolk Farm' Part II, HWSJ 40, September 2004, pp. 22–35.)

On 27 March HW wrote a long letter to Cyrus Brooks (his agent) of which a carbon copy exists in the archive. It is obviously in answer to one from Brooks, and contains much interesting material about HW's thoughts and ideas about his writing at this point.

7 April: 1st batch of Phasian proofs arrived.

(The next day also saw the arrival of the proofs of the new highly revised edition of The Star-born.)

A further batch of Phasian proofs arrived on 13 April.

17 April: Sent “Note on the Pheasant” to Strand Magazine. [The title of this article was revised to 'The Phasian Bird'. This article does not appear to have ever been published, but a typescript copy is in the archive.]

On 19 April a telegram arrived from Leslie Periton of Chenhalls (HW’s accountants) indicating:

Happy report offer accepted. Letter following.

It seems that his Income Tax problems with the Inland Revenue were now resolved. There is no comment, but on 24 April HW sent off instructions to sell stocks and shares he held:

to pay £2,250 due to Inland Revenue.

This (at that time) huge amount does seem excessive in view of earned income less justifiable expenses. HW had already noted that he had paid £300 on 18 February as 'provisional payment of Schedule D for 1947‒8': which sum seems a reasonable amount for that year's accounts. By deduction, it can only be that this large tax-due sum was connected to the sale of the Norfolk Farm, which would have been a complicated affair. HW had been having urgent meetings with his accountants and an Inland Revenue official at Bury St Edmunds while at Botesdale, and the fact that he had had to itemise 'Beneficiary' money received by both himself and ILW back in 1936 (used for the purchase of the farm) would bear this supposition out. Richard Williamson remembers that his father was very worried indeed about this at the time.

On 5 May 1948 Ann's note in the diary states: ‘HW acquired the Adelphi Magazine.’ There is a separate entry in 'A Life's Work' on The Adelphi.

The entry for 9 May notes that HW had agreed to loan part of the Phasian Bird MS and a first edition of The Beautiful Years to Suffolk County Library for an exhibition: a second entry for 13 June shows this to be for 'Festival of Music & Arts' at Aldeburgh for 5‒13 June. (Aldeburgh being the home of Benjamin Britten.)

12 May: Corrected proofs of “Phasian” sent reg. for £100 to Faber.

On 18 May HW wrote to Charles Tunnicliffe (the artist who had illustrated Tarka the Otter and others of HW’s books) asking if he would do the jacket for Phasian. A few days later there was a reply turning it down, as unfortunately he was too busy.

At some point previously HW and AT had travelled to Botesdale, for the diary notes that they now left there on 21 May.

26 May: 1st batch Phasian proofs arrived.

Arriving at the same time were the proofs of HW's article for the current Adelphi magazine – 'Birth of the Phasian Bird', an article obviously designed to interest readers in the forthcoming book, although that is not given any mention. These were corrected and returned to 'Hogan', sub-editor of The Adelphi.

HW now wrote to R. A. Richardson (artist/ornithologist of Cley, Norfolk, whom HW had met during the Norfolk Farm era, and who had befriended young Richard, encouraging his interest in ornithology) about the possibility of illustrating The Phasian Bird. In due course (4 June) RAR replied saying he would like to have a try at it – but there is no further mention of this project at all. Probably by the time HW informed Faber they had already dealt with this, as shown below. However, Richard Richardson would later provide charming drawings for a series of articles that HW wrote for the Daily Express in the late 1960s/early '70s, which are reproduced in Days of Wonder (ed. John Gregory, HWS, 1987; e-book 2013).

28 May: 2nd batch of Phasian proofs arrived.

And the Star-born proofs which had arrived the day before, had already been corrected and were now sent back. This all meant very intensive work for HW.

29 May: Further batch of Phasian proofs.

That these were all dealt with and returned is evinced by entries for 12, 14, & 16 June, when fresh galley proofs of Phasian arrive.

Over 18‒20 June HW went to Swindon for the Richard Jefferies Centenary Celebrations (see the 'Life's Work' entry for Richard Jefferies).

The diary notes on 28 June the receipt of a letter from Richard de la Mare, informing HW that he is getting 'the Star-born illustrator to do the jacket'. One senses Dick was getting a little impatient with the situation! As HW had dealt with the proofs of the new edition of The Star-born he must surely by then have seen Mildred Eldridge's illustrations for that book – but there is no comment whatsoever. They are very sensitive and have a strange beauty, fully complementing the spirit of the book.

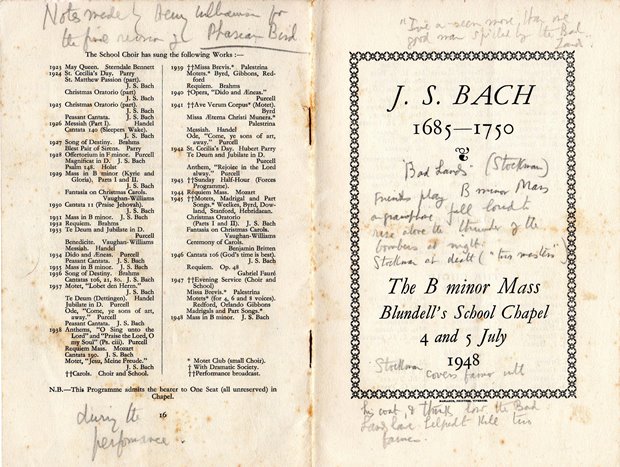

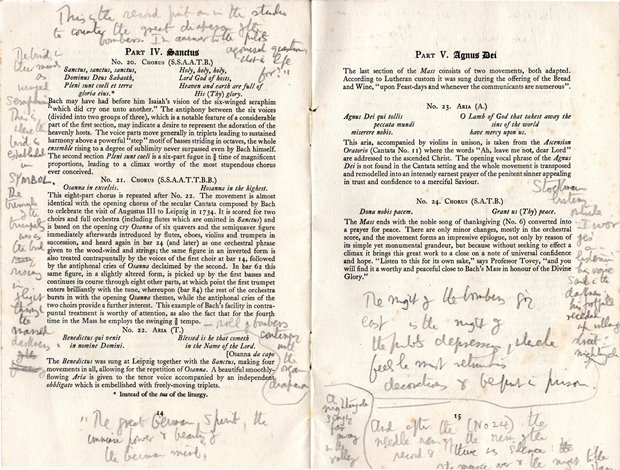

On 4 July HW attended a concert at Blundell's School, Tiverton, of J. S. Bach’s Mass in B Minor, where his son Robert was singing in the chorus (Richard was still at St Michael's, Tenbury). He made notes in his programme for a revision of The Phasian Bird – to include this work as a record put on by Wilbo:

Note that at this point that the book is now at an advanced stage of production! Richard de la Mare, as became clear much later, was evidently getting rather annoyed with the problem of HW continually changing things within this book: costs must have escalated enormously.

9 July: Finally corrected galleys of Phasian Bird posted to R. de la Mare at Much Hadham, insured £400.

14 July: Letter from R. de la Mare re libel in Phasian possible.

On 15 July there appears the last entry in Ann Thomas's handwriting. (She returned to her home in Malvern, ostensibly to run the business side of The Adelphi.) The diary is from then on more or less blank, except for a couple or so business memos.

It was at this time – the actual date is unknown, 'summer' is the only reference given later – that young Christine Duffield and her brother turned up at the Field while walking around North Devon. Christine was either already teaching at a school in nearby Bideford, or started there that September. HW fell in love (precipitously as always), and they were soon living together as man and wife with marriage planned for January 1949. In the event, it was postponed until April.

This was a severe blow for Ann Thomas, who had presumed, understandably, that with HW's divorce, he would marry her. Nonetheless, she now undertook the considerable work needed for the production of The Adelphi from her home in Malvern. Somewhere HW notes that he bought The Adelphi in order to provide work for Ann so that she could be independent. I feel that can hardly be true: it just turned out that way in the new circumstances.

The contract for The Phasian Bird was not signed until 20 August 1948 – by which time the work was, of course, already in proof and possibly already at print: a very unusual proceeding. The royalty was 20% (other than exceptions) with a total advance (as agreed earlier) of £1000. But as explained, HW had already received £250 for the non-existent 'Fergaunt the Fox' book, so £250 of this payment was already nullified. Again oddly, alterations to accommodate this were not made until the signing of the contract.

HW's diary notes (the only entry at this time) on 1 September:

Paid in Bank for Phasian advance £500

The only other brief entries reveal that on 3 November he travelled to London (on Adelphi business).

5 November: The Phasian Bird published.

[HW gave] Party to 8 critics and fellow authors at Savoy. Dinner & dance.

The previous day he had:

Sent off 12 copies of Phasian Bird to various authors for publicity. £5.--.--.

On 11 November he received the remaining £250 advance on publication.

*************************

The book is divided into four parts with a total of 29 chapters, but there are no headings and no further quotations, so that there is no interruption to the flow. We are told in the blurb that the opening is set in the winter of 1937, and so therefore set at the time that HW spent his first (very difficult) winter on the farm. Regular HW readers would have The Story of a Norfolk Farm well to the fore of their consciousness. (And I would remind you that a map of the farm and its fields can be found within the 'Life's Work' entry for that book.)

The story opens with a description of the Carr:

At the western end of the meadow there was a wood called the Carr.

Note that, as in the opening sentence of Tarka the Otter, this is (as so-called by T. E. Lawrence) a 'feminine' sentence – that is, 'passive'. The word 'carr' may possibly be a local Norfolk word: it usually designates willow and other trees growing in a wet area. It is probable that HW's handwriting was misread here, as he changed the text to 'eastern' at some point – though it ends up 'western'!

Further reminiscence of Tarka is the slow and considered opening tone, as HW paints for us a scene of time past, then the present: and we meet a main feature of the book, the ivy-clad pine tree:

There was an ivy-clad pine tree growing at the northern end of the Carr. . . .

The wind, that ever seeks song, drew from the pine tree with every wandering air a sibilance, or a humming, or a roar. . . .

At the time of the winter solstice there began to move over the western hemisphere the long thrust of Siberian air which drove down every winter from the Pole. . . .

We are told the farmer is in debt and the farm is in a ruinous state. Life was very hard.

There were over two million men without work in Britain.

This is before the welfare state: if frozen weather meant no work on the farm, then the men lost that day's pay – six shillings.

We read of the plowman plodding behind two horses. Life is not easy, but work has its own rhythm.

Snow sets in (HW's variations on a cold theme as the book progresses are superb):

Again the wind was drifting as the spirit of ice over water and land, the snow streaming a spectral smoke with the moving airs.

We meet the creatures who live by the little river: a hungry heron, a young playful otter, and 'a dark bird with mincing steps' (a moorcock); and, with 'a sound as of hounds baying from on high', the wild geese. Then a 'fall' of short-eared owls from Scandinavia, one with a gold-crest wren on its back (echoing an old legend), together with a further fall of woodcock. (A 'fall' is a flock of birds arriving exhausted from crossing the sea in bad weather, and literally falling into bushes along the shore-line – where they are easily killed by those hunting prey, including man.)

All are familiar from HW's recent and past writing, but painted afresh: one is greeting old friends.

A shoot is held – cocks only: as is the tradition at the end of the season. The hens are to be let live to breed, but someone does shoot a hen and gets shouted at for his disrespect. Some of the members of the shooting syndicate will play a bigger (and nefarious) role in due course. We read of the brindled lurcher, Bingo, who follows the shoot, and the tale of the hen pheasant, whose leg has been shot, then nearly pecked to death by Gallinule (the moorcock), but who escapes, watched by Harra the Denchman, the grey hooded crow, a feature of the Norfolk coast in winter (fleeing Scandinavian cold: 'Dench' is old word for 'Danish'). And so we come back to the ruined farmer and the appalling state of farming 'towards the end of the fourth decade of the twentieth century.'

The cold spell does not last long and the plowman (HW always used the ancient spelling), helped by a young lad, can get on with his hard work, followed by screaming gulls. The now one-legged pheasant has learned how to cope, as prepared by:

two thousand years of northern living since the Romans had brought to Britain the coloured birds of the swamps of Phasis, a river in Colchis. . .

(Tegetmeier states that the earliest record was in a 1059 manuscript, and that Roman invaders probably imported it together 'with other imperial luxuries'.)

Dusk falls and the men go home, leaving the field to the wildlife. Morning brings work. HW describes here how things were: how the slackness of boss and men were the very cause of the farming depression. 'We wun't be in no muddle' was the battle cry of the Norfolkman (and heard so often on the Norfolk Farm! Note the double negative, a feature of the Norfolk dialect.) We meet the men, the teamsman and his father, the stockman.

Then Harra the Denchman returns across the sea to his northern forests, while:

the vernal impulse came from the sun, lord of all physical living.

All living creatures obey the impulse of spring: kingfisher, ring-dove, woodpecker, skylark, lapwings – whose nests in the ploughed land were so vulnerable to 'the iron of hoof, or shoe, or tool', as Smiler and Blossom pass pulling the harrow (readers will recognise the horses’ names), but whose eggs are moved out of harm's way by a friendly human hand.

This is a deliberate description of farming in the old slow country way, a way that had existed really for hundreds of years. Its innate difficulties were exacerbated by the mental attitude of those who worked the land.

A cock pheasant (an ordinary 'game' pheasant) takes centre stage, with a magnificent description of his colour in full breeding plumage. One of his harem of hens is the one-legged pheasant. She lays ten eggs in her nest in a nettle patch at the foot of the (the) pine tree. Then one morning, before she starts to sit, a man carefully approaches and replaces four of her eggs with four from his pocket.

It is not made clear here, deliberately – but I think it is worth clarifying at this point that the man is actually the farmer who is facing ruin. The hen pheasant lays three more eggs herself, and then starts to brood. (Birds do not start brooding until all eggs are laid, usually one a day – so that they hatch at the same time.)

HW describes how the growth inside the egg reflects the millennia of life since 'the cooling vapours of creation'. His own creative powers are working at their most intense.

Eleven eggs hatch, and in due course the hen pheasant moves them out into the meadow of the Carr. Hesitantly they make it. HW's 'Rest, my little ones, rest; all is not self, all is not fear' has an almost Biblical ring to it. But of course one knows that any such family is in constant danger. Her peace is disturbed by an otter, and that leads in turn to a stray tom-cat. The cat comes into conflict with the hen pheasant, who out-stares it (cats do not like this!), and she leads her chicks to safety.

Now a cuckoo comes on stage: stalking meadow-pipits for her own egg-laying, and frightening the hen pheasant as it passes over her with its own weird bubbling witch-like cackle (the female's noise). (One would have thought that there were enough reed and sedge buntings in that area for cuckoo parasitation, but that's how HW wanted to portray this scene!) The noise the hen pheasant makes attracts the attention of the murderous moorcocks, one of which is Gallinule. They kill a chick, and their noise attracts the cat back, which then kills the hen pheasant.

The Stockman, on his way to inspect the bullocks grazing on this meadow, finds the cat running towards him chased by an otter. On seeing him they stop dead – and flee. 'Thar's a rum 'un!' exclaims the Stockman, and continues on his way, unknowingly passing a pair of partridge, Pertris and Pertrisel, 'whose chicks, scarcely larger than bumblebees, had hatched that morning'.

(Throughout the book the word 'stockman' is printed with a lower case initial letter only: he is never named as such, and as he is just about the main character, here I intend to give him a capital 'S' to signify his importance. The wretched Flockmaster does get a capital letter!)

The scene returns to the confrontation between cat and otter and its aftermath: the moorfowl return and with stabbing beaks eat the dead pheasant. (Possibly for most readers this is their first knowledge of the rapacious habits of this seemingly charming bird!)

Re-enter the partridges, shepherding their chicks with great care with a lovely (and loving) description of the male's plumage, and

Unlike the gaudy Asiatic . . . with his harem of dun hens left to fend for their families, the cock partridge was loyal, meticulous, and brave in care and defence of his mate and young.

(This is totally correct: pheasants are not good parents – partridges are excellent.)

Only a single pheasant chick has survived the moorfowl attack and now, failing fast, cheeps very feebly, falling into a cavity made by 'a cloven [bullock] hoof '. The partridges settle for the night – beside that cloven hoof print – and the dying pheasant chick creeps into the warmth of the male Pertris, who, although slightly surprised, also settles for the night.

At dawn the next morning life on the meadow stirs again – with a lyrical description of a natural Eden (think Delius' dawn music):

Light flooded over the rim of the ocean, the sun rose and cast thin green shadows amidst the gold-spiked grasses . . .

Pertris is again puzzled to find an unfamiliar chick beneath him but as it cheeps he accepts it: the hen partridge ignores it.

The scene shifts subtly to farm work, with intricate detail involved in hoeing sugar-beet: then it is time to mow the hay field with noisy machinery. The partridge family become trapped in the decreasing middle. The farmer, weary and useless but of true country heart, stops the cutting to save the bird. A chick moves and the farmer picks it up. The cutting resumes. Pertrisel is still in there with her own chicks. Despite the men's care, inevitably she is killed – only one chick survives.

By 9 p.m. the work is finished. The farmer takes the chick out of his pocket and examines it, showing the Stockman. He recognises the markings on the bird as 'pheasant', and then that it is actually unusual: it is from the eggs that he had put in the nest of the Carr pheasant. He tells the Stockman:

‘The Chinese call the bird Chee-kai which means “arrow-bird”.’

He puts it on the ground near the dead partridge, thinking it will find its way back to its parent, although puzzled that he had not seen a hen pheasant anywhere. When all is quiet Pertris emerges, at first calling for his mate, later roosting and brooding the two remaining chicks.

As Part Two opens we read that the farmer's desperate financial plight overcomes him. Hounded by his bank manager and creditors, he takes his gun and, going off to the blackthorn brake in the Carr area, shoots himself. (This was not uncommon in those days of desperate farmers. Indeed HW was almost brought to this state several times, when the work and the debt overwhelmed him.) The noise of the report startles Pertris and the two chicks. The nearby bullocks have their own problem: they are bedevilled by warble-fly. To get relief one pushes into the blackthorn brake, where it senses a strange smell, and sight ‒ the farmer's body. The bullocks push down into the dyke to drink for relief: one is a fearful 'under-bullock'. Warble flies attack again and the small herd stampedes out of the area, leaving the 'under-bullock' stuck in the dyke. (Readers will remember that a similar bullock features in The Story of a Norfolk Farm, where it eventually dies.)

The Stockman arrives to count the bullocks, finding the disarray and wonders what to do. He notices the partridge and two chicks and that one is odd-looking, and he realises with pleasure that it is the chick the master had shown him: master will be pleased. But as he trudges off to find the bullocks he comes across the sad scene of his master's dead body.

He covers the shattered head with corn stalks and continues on his way to collect up the strayed bullocks. When this is done he goes to the hay field, where the men are working to cock the hay, and informs his son (the teamsman). They decide to get the constable and a tumbril to move the body – and a rope to get the bullock out of the dyke. They wonder what will happen to the farm and themselves: but know work on the farm will have to continue for the time being.

Chapter 9 opens with Chee-kai and Pertris and the remaining partridge chick centre stage. They encounter a rat, and Pertris bravely harries it. It starts to scream – but not because of Pertris, but a greater enemy: a weasel, a creature 'created with more sun-fury than most animals', is on its trail and, having mesmerised it, soon dispatches it for its blood. Pertris reacts noisily, launching himself into flight and commanding the two chicks to follow him. They are seen by the Stockman.

So things continue: the farm is overseen by the dead farmer's creditors from the bank. The situation regarding debt and farm process is summarised. All will be resolved on Old Michaelmas Day (11 October – in all the farm writings HW bides by this older date rather than today's 29 September.)

A stranger (HW has the Stockman call him a 'foreigner' – the Norfolk word is 'furriner') walks round the farm fields. He sees the partridge trio and realises one of the birds is unusual. He carefully gets out his 'Zeiss monocular glass'. (Regular readers will know that HW retrieved a Zeiss monocular from the Western Front in the First World War – so we know who this 'furriner' really is!) Although he has studied birds for many years he has never seen one like this. He retreats carefully so as not to cause disturbance, and goes off to find the Stockman.

They discuss the strange bird, and then the stranger says that he plans to buy the farm, although everyone he knows says that farming is finished.

The scene returns to the partridge trio as a thunder storm approaches (with a page of superb description). A torrent ensues, and despite all his efforts Pertris is swept away:

the chicks were lost to him.

Thinking this a good time to observe the farm, the stranger goes round again. He comes to the storm spate and sees the small bird he had previously noted now woefully dirty and wet. He picks it up and places it inside his shirt to dry and warm it. He sees the male partridge, very bedraggled, and looking around finds the other chick, rescuing that also. Sitting down he thinks things over:

What a queer beginning . . . he wondered how would it all end.

(This echoes the 'In my end is my beginning', the words embroidered by Mary Queen of Scots, and used later by T. S. Eliot in 'East Coker' of his Four Quartets; a phrase that HW reiterates more than once in his later writing.)

The stranger returns the two chicks to the male partridge: they are seen together by the Stockman the next day.

The farm workers get in the harvest, where there is as much thistle seed as barley. Readers will remember the struggle HW had with thistles during his early time on the Norfolk Farm.

On 1 October pheasant shooting opens. The syndicate has bought the 10 days up to Old Michaelmas Day – the day the farm will be officially sold. They intended to get every bird they can. The shoot and its guns are described in HW's usual superb style: penetratingly exact. The partridges are in danger, but after a scare they escape to quieter ground and stay there until this burst of shooting stops on the sale day, when all becomes quiet.

Chee-kai comes to full maturity in a comparison with normal game pheasants. There is no shooting, the new farmer is too busy relaying the roads with chalk. Cottages are being renovated: the locals of course don't 'hold' with such new-fangled ideas (just as HW found on the Norfolk Farm). The new farmer knows he has taken on more than he knows how to cope with.

Nature continues its age-long course:

Glittering low in the south-eastern sky the great constellation of Orion shook its gemmeous fires upon the air, while from under silver-edged clouds came the trumpetings of geese which had flown down from far Spitzbergen.

The new farmer 'was determined to have no compromise with the old, lest it confound the new . . .' So it was 'all go', as Norfolk folk describe hard work. The time for threshing arrives. Readers will know this scene from The Story of a Norfolk Farm, but here, as part of a novel, it comes to life in a fresh way. A chance remark gives the farmer a nick-name: 'Wilbo', and so he becomes known. The men have seen him in the barn at night apparently drawing something on paper pinned to a board by the light of a hurricane lamp. (It is interesting that HW makes Wilbo an artist: he evidently saw himself as a painter, as indeed he was – of words.)

Snow arrives: the partridge trio crouch in shelter, Perdix the young partridge always perching on Chee-kai's back.

Gyr the white falcon swept in from the sea, cutting sharp-winged down the blizzard, swinging up to hang watching, cutting short circles . . . [hanging] sharp in the grey streaming wind, flickering as he watched, as he rose upon the gusts without falter . . .

Beautiful bird – wonderful sight: but

There was a screaming hiss, a craking cry from Pertris who seemed to burst upwards in feathers, another as talons struck the young partridge . . .

Perdix has been lifted off Chee-kai's back and killed in an instant.

Momentarily stunned, Chee-kai then rises in instinctive terror-stricken flight to escape the killer falcon. He lands in

the dark green needles of a pine tree, enclosed in ivy . . .

He has found sanctuary in the pine tree which is described at the very beginning of the book: the tree at the end of the Carr, under which Chee-kai had emerged from the replacement egg.

A new spring arrives: a pheasant filled with testosterone hormones attacks Chee-kai, only to meet a stronger opponent. At that moment however, Chee-kai hears the call of a partridge, his partridge: Pertris. The call is also heard by a young hen partridge. Both hasten towards the call. Pertris has a new mate; but also nearby stayed:

a bird of shimmering plumage like to gold on its back and deepest black on its lower chest and belly, carrying behind it an immensely long sweep of tail, of feathers grey and buff barred in chestnut and cinnamon – a bird matchless, and therefore solitary . . .

A new tractor arrives: the Stockman's 'Blast, I what you call like that patent' is another echo from the Norfolk Farm. But he is worried that it means Wilbo will get rid of the horses – his livelihood.

A corncrake arrives and also a quail: 'crake, crake, crake' joining 'wet-my-lips – wet-my-lips' (sadly, sounds rarely heard today).

The teamsman and his father (the Stockman – readers will have realised they are based on Bob and Jimmy Sutton of the Norfolk Farm) discuss Wilbo's strange methods on the farm, which the village folk find daft. Wilbo is cutting the rushes and reeds and then piling them up, then shifting mud up out of the grupps (dykes), and has made a concrete bridge where wood has always been good enough. The men are puzzled and worried. Enter the Flockmaster (nickname of the rag-and-bone man), who adds his half-penn'orth to the ruminations for his own purposes.

The Stockman has heard the previous night in the pub (the 'Norfolk Hero', named after Nelson, born nearby) that a gang plan to sweep-net the upland fields of the farm for partridges. He has his own plan. He waits in the local pub (the 'Horn and Corn') and the reader is treated to an amusing account of the rather drunken and stupid behaviour of this gang, first in the pub and then in the fields. But the Stockman has 'sown' the area with thorn branches, and all the gang catch is a net full of thorns, torn to shreds, and themselves distressingly scratched! (The Stockman's ploy is typical of crafty Norfolk behaviour.) Pertris and family, and the 'long-tail', are safe.

Plowing with the 'hydraulic' tractor: gulls following. The tractor driver is not named, but it is Wilbo. Going home that night he sees the partridge covey

accompanied by the brilliant pheasant which his mind was beginning to regard as a symbol of resurgence and beauty.

Next day, plowing is interrupted by a gull caught in the turned furrow (again, as in The Story of a Norfolk Farm). While releasing it the farmer realises a shoot is in progress on the neighbouring farm: and that his partridges and Chee-kai, who had been habitually feeding there, were likely to get trapped by the (deliberately) clever strategy of the beaters. HW gives a detailed description of the stand and the movement of birds towards inevitable death. But

the pheasant with the long tail flying faster than the covey of partridges [as discussed by the guns afterwards] . . . which had appeared to lead the covey away from the line of guns at the second stand. It had flown on to the land of the newcomer whose presence in the neighbourhood was something of a mystery, and had not been seen again.

The shooting season is over and things are quiet again. Wilbo buys some Rhode Island Red pullets (a breed of chicken) and we read their tale. But a jackdaw is after their eggs, and so the Stockman shoots it: Wilbo is worried that he had hit Chee-kai, who alarmed at the noise had flown off and landed back in the lone pine tree of Carr wood. He now lives a solitary life.

The seasons turn: the corn harvest on the farm was good – the best barley in the district. The Stockman is pleased for his master, but the Flockmaster praises him in a crafty insinuating manner. Poison is being dripped into ears.

There is a heavy fall of snow. Chee-kai stays ensconced in snow-cover at the top of the pine. Wilbo, who has been concerned as he had not seen the bird for some time and fearing that the bird had been shot, now looks through his monocular and sees the bird's plumage showing at the top of the pine.

He is being watched by the poacher, who decides this behaviour proves that he is a spy:

For now that war had come, the new farmer was the subject of much talk and suspicious regard in the locality.

Soldiers also are patrolling the marshes with orders to watch and arrest anyone signalling out to sea. (It is now February 1940.)

The frost hardens but all is well on the farm: the red-polled heifers were warm and content in their own yard by the stacks. One day, as the farmer watches them, he sees:

a cinnamon-coloured cockerel, with a smoke-grey mantle of feathers on its back . . . with tail feathers sprouted in a flaunting curve of smoke-grey and light brown . . .

This bird has been born wild. The farmer's wife comes to feed the turkeys, who follow her

with long striding steps, like animated old and tattered umbrellas . . .

The wild cockerel challenges them with his call, and the farmer discovers he has a hen pheasant as companion and possible mate. The description of this encounter 'with the umbelliferant cohort' is delightful.

The cacophony of this encounter stirs Chee-kai. He comes down from the pine tree and makes his way, avoiding a weasel, to feed with the partridges, the wild cockerel and his hen pheasant. Harmony among friends – disparate though they may be – is the message.

That night the poacher shoots a pheasant on Wilbo's land and gets away. Then follows a scene of the otter playing on the ice in the dyke.

Chee-kai roosting in the top of the tree heard the fluting wader-bird-like whistle of the otter on its way home, and settled more securely into his warm eyrie of snow.

We move into May, the pheasants are nesting. Rather sinister black smuts fall from the sky. They have come from burning oil tanks across the sea. Five men in city coats and hats appear and ask for the farmer by name. They spread out and surround Wilbo – and arrest him. Telling his wife calmly that he has to go away, he leaves instructions for the immediate work of cutting and carrying the precious hay crop. He asks if he might take his painting gear with him (just as HW had been allowed to take paper and pens with him when he was briefly arrested). This arbitrary arrest is made under Defence Regulation 18B, although this is never actually stated.

Life among the wild creatures and on the farm continues. The farmer's wife feeds the turkeys, and their six-year-old son with his own little painted bucket excitedly scatters barley and currants for his father's favourite bird. His mother remembers that she has to give instructions to the men about the hay, and leaves him alone, and, slightly frightened, he wanders off, leaving the gate to the turkey pen open.

The boy wanders along, dropping now two grains, now three, now a currant (he liked currants but would not eat one from the pail, as they were for the 'faysan' bird). He sees the wild cockerel followed by the partridge family and the hen pheasant with her (and the cockerel's) hybrid chicks. The turkeys having escaped, they now attack the chicks – defended by the cockerel although he is outnumbered. But the Phasian Bird – described here as a 'golden bird' (and perhaps why some critics of the book referred to the bird as a 'Golden Pheasant' – a totally different species) rushes in and overcomes the two stag turkeys, who clear off.

The boy is thrilled to have seen the 'faysan' bird. However, they return home to find several men searching the premises and removing items, including paintings, from the barn studio – which might be disguised maps useful to the enemy!

Part Four (the final part) opens with a lyrical description of night under the moon, with the song of nightingales and reel of grasshopper warblers, sedge and reed warblers. Summer passes, the harvest is gathered in. The ominous rumblings of bombs are heard, and searchlights disturb the night sky. Troops pillage the countryside.

A paragraph opens: 'Yellow and black and brown, the leaves streamed . . .'. There is a very similar passage in Tarka the Otter, but translated here to fit the Norfolk scene: the natural decay of life. This is followed by a scene of unnatural decay of the countryside caused by the war work: the pillage of the natural world by avaricious man and his war-machines.

Chee-kai is an obvious target, but as his natural impulse is to hide in cover he is surviving. Many other birds that have graced this story have succumbed (including the turkeys): shot by the very crafty poacher with a .410 shotgun, who is supplying a local collector of rare birds. Chee-kai has the price of £20 on his head. We learn also of the Flockmaster's nefarious profiteering on the black market.

The price for Chee-kai is increased to £30 if in good condition. The poacher and the Flockmaster collude on how to achieve this. The Flockmaster secretly buys a game-cock from a man in a nearby inn. While they clinch this deal, someone comes in with the news that: 'Wilbo's back.'

Here in the book, Wilbo has been in prison for 'years'. (I would remind readers that HW was never actually imprisoned, and spent only two days – three nights, a weekend – in a police cell in Wells, and was released without charge.) The life of the farmer's wife in this interim is described, which follows the thread of Loetitia's life during the war years, together with life on the farm without Wilbo to supervise. Only the Stockman has remained faithful.

On his return Wilbo is morosely solitary. One day his son comes to him in great excitement with news, but Wilbo shouts at him, and he runs to his mother. They try again, and Wilbo, realising they love him, embraces his son.

There is a rumour that the farm (now very run down) is to be taken over by the 'War Agricultural' (W.A.E.C. – War Agricultural Executive Committee) – and it does so. The Stockman gives in his notice. The pages describing this process make sober reading. This, of course, did not actually happen on the Norfolk Farm, and the whole chapter is deleted from the American edition of the book. It is a totally convincing scenario here, and no doubt did happen on many farms.

The result is that Wilbo becomes even more depressed, shutting himself away in his studio and doing nothing, becoming:

as one turning slowly to stone under the unending stalactite drip of tears upon the core of human consciousness.

His comfortable room, with all its treasures, full of their own meaning and memory, are as nothing.

And on the chimney piece, curled with damp, were reproductions of Albrecht Dürer – grasses in natural colour, of a hare cut in wood . . . still unsurpassed throughout the world for their clarity and truth.

The bombs had brought all to the dust.

The allegory is plain to see: war has destroyed the good things – the beautiful things of the spirit – of both England and of Germany. HW did indeed have copies of those two examples of Dürer's superb work and they were displayed in his Writing Hut throughout his life.

A new chapter opens with a memorable paragraph: HW at his best.

As of a great organ with all the low range stops out ('diapason' is a term for the harmonies of this), the bombers roar high across the farm on their way to Germany. The effect of these words is as shocking as Paul Nash's Totes Meer painting. HW's image merges into that of hooded crows, including Harra the Denchman, leaving in March. They are seen – hopeful sign of nearby land – by one of four surviving American airmen floating in a dinghy from a ditched Fortress.

The farmer's son is now 10 years old: 'he loved the land and all things natural upon it', and knew where every bird's nest was on the farm premises. (The lad is based on HW's son Richard, youngest of the family during the farm years.) Despite his father's reluctance the family set off for a walk round the farm. The neglect of the once-new roads, gates, posts, hedges – and thistles again – everywhere is depressing. (We learn here that Wilbo had been a scout pilot in the RFC in the First World War – HW's wishful thinking, perhaps!).

At the barley field they find a gang of men spraying 'a yellow mist of liquid' over the corn and weeds alike . . . the sprayed liquid withered all life that it covered.’ This was a dangerous chemical that needed protective clothing and great care in its use. No precautions are being taken. The next day they return to see how much damage has been done. It is a depressing sight. This carelessness was very common at that time: one of which HW was only too well aware.

They sit down and recover equanimity lying on the grass in the sun, surrounded by wild flowers and bees. They hear a partridge call. It is Pertris – but the other birds are dead in the sprayed barley field.

Wilbo's wife, alarmed at her husband's increasing violence about the effect of the war, sends for the doctor, who knows that what the man needs is a psychiatrist. He notices the paintings hung on the barn wall have been turned inwards to face the wall and asks to see them. He had heard about the pheasant with 'the extraordinarily long brown-barred tail' (the subject of many of the paintings).

‘My dear fellow, there is genius in the hand and mind that painted those pictures . . . You must paint, do nothing but paint!’

To help Wilbo, the doctor decides to introduce the American airman-poet recently washed up on the Point of Terns (Blakeney Point – a famous bird reserve on the North Norfolk coast near Stiffkey), but knows he must do this carefully. (This is the man in the dinghy who saw the hooded crows.) On leaving the doctor sees Wilbo's young son out bird-watching, and offers to take him across to the Point to see the terns.

Wilbo stands leaning on the wall of his studio barn in warm sunlight and wills himself back to a balance of life:

feeling that the purpose of human life was to bear its part in the eternal struggle between light and darkness, as it had been waged in the soul of every poet and visionary since the creation of mind.

This expresses the essence of HW's personal ethos: the eternal struggle of good and evil – 'light and darkness', with its roots in Platonic thought: his 'Lucifer' concept.

While Wilbo is thinking, his son arrives with a tall uniformed (8th USAAF) young man with blue eyes and fair hair. Wilbo takes to him immediately. The young lad is shouting:

‘Dad! Dad! We have found the Phasian bird!’

Chee-kai had found sanctuary in the Willow Plot on the Home Meadow . . .

The meadows were not ravaged by poachers, nor by Italian prisoners of war – 'Co-operators' –, soldiers, nor locals, for various reasons, not least that they were inhabited by a fearsome bull, 'Townshend Toussaint the Tenth'. Chee-kai, with the innate craftiness of his species inherent in his nature, kept hidden and unmolested, accompanied by faithful Pertris. Lying in the meadow kingcups (the large golden marsh marigold), he had been discovered by the young boy and the airman. The author's words here extol the healing process of innocence on a troubled mind.

Thus began a friendship between two men which was to continue until death, and even beyond the chiaroscuro of terrestrial living.

There is a happy simple picnic tea when the family and new-found friend sit and watch Chee-kai feeding nearby along with Pertris. (The real-life identity of the airman is not really known: I had thought it was based on George Mackie, who visited the farm and became a family friend (see HWSJ 32, September 1996, 'Brief Encounter', pp 18-23), and also 'Crasher', the airman that Edward Seago lived with, who was killed in action, but as HW came across the poetry of James Farrar at this time – a young airman who was killed while attacking a German V1 rocket – perhaps it is more likely to be him. Mainly he represents that generation of brave airmen who were killed in action.

That sweet lull is momentary. The sensitive pilot-poet has to return to his task of flying (and it is this next phrase that suggests the man is based on Farrar): he

had yet to come to the full vision of the poet; but he glimpsed it that night . . .

In a superb passage we read how day became night – and Wilbo puts on a record.

This is the passage inserted at a late stage, written or envisaged while HW attended the concert at Blundell's School on 4 July 1948. One cannot imagine the book without this spiritually uplifting interlude, yet it so nearly never existed.

Summer comes to its zenith and the corn is ready to harvest. The lyricism of the Bach passage continues with descriptions of high summer, and the stars and sky at night – but always the bombers are passing overhead.

The two men and the boy watch the harvest being soullessly gathered in by the Italian prisoners-of-war. The young pilot is to return to duty: he asks if he may copy the painting of Chee-kai in flight on to his new 'ship'.

The scene turns now to the villains: the chief 'Wide Boy', who with the other 'Boys' are:

genuinely inspired by a devotion to the profit motive . . .

They are doing well out of the war by cheating over air-field work. These men are actually those of the shooting syndicate that jumped in 'to make a killing' when the farm was for sale at the beginning of the story.

The 'Chairman of the Trading Company' (one is reminded here of Richard de la Mare's warning note about libel!) is visiting the Flockmaster to buy whisky with which to enliven his planned poker game with the 'Boys'. As they get round to discussing their business, the 'Wide Boy' chief mentions that he has heard the farm might be for sale, and that he thinks of buying it. He plans to do this in an underhand (illegal) manner in order to cheat the Tax authorities, and enlists the Flockmaster's help. '”There's a hundred in it for you.”' The Flockmaster thinks he'll be made for life, for together with his other illicit earnings he will have enough to buy himself a smallholding. The plan is that he'll approach Wilbo and fix a price which will not be declared – thus both parties benefitting.

So putting on his best clothes, he goes off to call on Wilbo, who is unusually affable. Wilbo decides to paint him and sets to, although the Flockmaster is a little suspicious about his motive. However, both are pleased with the result. But while Wilbo goes to get some beer, the Flockmaster, noticing the paintings of Chee-kai on the wall, questions the lad about the bird, asking if he has seen it lately. The boy doesn't answer: answer enough. The Flockmaster leaves without mentioning the actual reason for his visit!

The wily Flockmaster then gets up early in order to have a look-about and sees:

a pale movement by the edge of the Willow Plot, and knew what it was.

The Flockmaster has penned in his shed the fighting gamecock that he had bought, which he names Jago, and for which he has a secret plan 'in the autumn'. He has nurtured the black and red bird and kept it in prime condition, and has a pair of long sharp polished steel spurs to bind onto the bird's legs ready for combat.

At Michaelmas large plowing machines turn the fields to the envy of lesser farmers. (This is of course work done through the 'War Agricultural’.) The Flockmaster, skulking around the fields, spies quarry and releases his dangerous combative bird towards the feeding cock pheasants. Jago attacks a pheasant and, after a spirited fight, kills it with his steel spurs. The Flockmaster gathers up both birds and continues cheerfully upon his way,

as the steely sky was being riveted by the first squadrons of the 8th Air Force . . .

One [bomber] had upon it an unusual device: a pheasant with white, black, yellow and russet-brown feathers upon its head and body . . .

the captain of which had been invited to spend Christmas Day in the farmhouse, to listen to

the music of Bach, of Delius, of Wagner, of Elgar, of Beethoven, and relax, relax, relax . . .

Chee-kai is still safe in the Willow Carr.

The doctor has suggested that the isolated and depressed Wilbo should join the shooting syndicate with his neighbour Harcourt, (as HW actually did with neighbouring farmer Charles Case). There is an interesting passage on the financial and social benefits of shooting, but Wilbo fears that if he opens up his farm to shooting then Chee-kai will be at risk. He feels he should submit to the world of man but:

Beauty never could prevail, nor truth, nor rarity, only the commonplace . . .

The thought is taken from the poem by Keats:

Beauty is Truth, truth beauty – that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

('Ode on a Grecian Urn')

Wilbo ponders on the strange (as in awe-inspiring) relationship between the wondrous 'Arrow Bird' and the common grey (English) partridge, 'true spirit of the soil of England'.

As the bombers, including that of the young American poet, pass overhead, Wilbo is trying to express his passionate emotions in paint (as HW was trying to express them in words in this book):

Rather amusingly Mr Reeves is denigrated alongside Earl Grey and his famous tea!

He ponders whether to sell the farm, as has been hinted at to his wife by the Flockmaster. Feeling a failure he cycles off to watch Harcourt's shoot on a cold frosty December day. He wishes he could be part of the scene, as it begins to snow.

The bombers return, recorded by the radar, and by watchers of the Observer Corps as they cross the coast, in a detailed and harrowing passage. A pilot badly injured in a severely shot-up plane comes in over the Point of Terns. The crew bail out, but the plane crashes beyond the High Wood in an explosion of fire.

(There is echo here of the death of Manfred in The Gold Falcon, drowning in the Atlantic with a similar experience of a golden bird spirit: there, a falcon.)

Wilbo, cycling home with difficulty in a sudden blizzard, hears the crash. He shelters next to a straw stack and watches as the vicious wind destroys it, straw by straw, 'until the entire stack seemed to be rising in wild disintegration'.

This crescendo of death by fire and destruction by blizzard ends with a vivid description of the transmuted landscape.

Chee-kai roosts in safety in the ivy-mantled pine, pecking at snow and pine needles for sustenance. HW's description of the landscape and the night sky is very powerful, and needs to be read and absorbed for full effect. Chee-kai, too, sees with startled terror the doomed plane, as if some legendary bird apparition, as it hurtles over his head to its violent explosion, making the earth rumble:

. . . as it was rumbling over the south-eastern sea, where in the Ardennes a great battle was raging.

Wilbo's wife and son are excitedly preparing for Christmas, the boy looking forward to the presence of his friend the 'Fort' pilot. The parlour is decorated and food prepared (quite a feast for war-time!). Wilbo was putting the final touches to a painting of the Phasian bird flying up to the sun. The telephone rings and the news it tells (of the pilot-poet's death – he was of course the pilot of the crashed plane) destroys all anticipation.

The Stockman celebrates Christmas quietly in his own way, then goes to the Horn and Corn. He is anxious as he has heard a rumour, and when he sees the American sedan car (symbol of decadence) of the chief 'Wide Boy' parked in the yard he is on the alert. The Stockman knows that his previous master (the farmer who committed suicide) had purchased four Phasian bird eggs (a life's dream) from a game farm and placed them under a hen pheasant, and that Chee-kai hatched from one of these eggs.

As he passes the Flockmaster's flint barn, he hears loud voices. The Flockmaster is entertaining four of the (Wide) 'Boys' gang and some American soldiers with illicit whisky alongside their own American cigarettes. The boys have come for duck shooting on the marshes, but delay for this conviviality. The poacher envies and fingers the machine guns of the Americans, wondering how he can get hold of one. As things progress, the Flockmaster shows off his fighting gamecock Jago, boasting of his prowess and saying how quickly it will overcome the 'goldy longtail'.

The great ambition of the Americans is 'To get me a Kraut'. To which the Flockmaster rejoins:

‘Thar's a Jarman livin' in this place . . . A Jarman, they say he is, Wilbo.'

The moneylender, pretending to calm things but really stirring them up, states that Wilbo is not a German, but that he is a fifth columnist. Having planted this thought, he abruptly changes the subject. (He does not intend to have any future problem laid at his door.)

Meanwhile Wilbo and his son have gone out into the snow, the one with skis, the boy with a new sledge. On his way down the village street he sees the Stockman, who hesitates over telling Wilbo what he heard, but Wilbo, seeing the American car approaching, hurries on his way. Seeing Wilbo going away from the farm, the duck-shooters change their minds: pheasants on the farm will be easier game. They convince themselves they are doing the world a good deed by providing food – which ‘the ——— that owns the land’ won't allow, thereby helping Hitler.

Wilbo is also seen by the American soldiers, and the Flockmaster tells them who he is: and together with the poacher they decide to go after pheasants (the pheasant) with Jago the gamecock.

All have presumed that Wilbo is making for the common hills where all the village people go to sledge, but Wilbo actually turns left in the village on to the southern hill road that takes them to the higher fields of the farm.

The soldier and poacher gang make their way carefully through the farm land: they hear geese going over, and then the call of a partridge: 'per-tris, per-tris'. HW builds the tension with great care and precision. The reader can feel the silent tension and hear the birds:

Per-tris, per-tris is answered by a frail rather sweet cry – the voice of Chee-kai.

The steel-spurred Jago is let loose, is faced by Pertris, and dispatches the brave little bird. Chee-kai rushes in and the two circle, feint, and lock. Chee-kai leaps up high and Jago lunging too late with both stilettos, misses and falls back. Chee-kai comes down above the gamecock attacking and piercing Jago's neck and main vein, and so kills him.

Wilbo, skiing down the slope and rounding a corner, comes abruptly upon the scene he has been dreading. He stops and starts to shout. Chee-kai rises like 'a golden rocket' and flies over him: the American soldiers firing at the bird with their machine guns. The Stockman, following their footsteps, hears the noise of the machine guns with awful dread, and galvanised into action, starts to run.

HW switches here to the 'Wide Boys', all pleased with themselves, especially the Moneylender with his Purdey (expensive at £200) gun. They have a hare and are on the look-out for pheasants. They too hear the noise of the machine guns and then see a magnificent bird flying high:

They watched it flying with amazement, the tail now compact and in a straight line like the shaft of an arrow behind the barb of whirring wings.

They would have shot it but it was out of range and not coming their way anyway; but they see it suddenly falter and fall lower, still continuing towards the Carr. It has been shot by the fourth man in the High Wood (the poacher).

The Stockman, running towards the scene, saw neither the soldiers creeping away, nor the Flockmaster hiding behind a tree, nor the poacher running off. Arriving at the scene he sees first brass shells lying about, then the dead partridge and fighting cock:

Then he saw the body of a man lying in the snow halfway up the slope.