THE PEREGRINE’S SAGA

And Other Stories of the Country Green

|

|

| First edition, Collins, 1923 |

Appendix: A Time-line concerning the writing of The Peregrine's Saga

First published by Collins, November 1923, illustrated by Warwick Reynolds

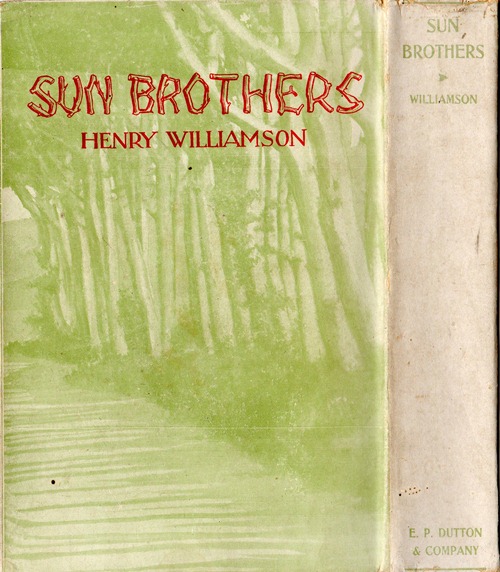

Dutton, USA, 1925 – entitled Sun Brothers

New revised edition illustrated by Charles F. Tunnicliffe, Putnam,1934

Reprinted many times subsequently

Dedication:

‘Inscribed to Esther Francis Stokes

for many deeds in amity’

(For an explanation about Esther Stokes see The Lone Swallows entry – and the later entry for The Sun in the Sands – AW’s biography Tarka and the Last Romantic, and Ted Stokes’ ‘The Owl Club’ in HWSJ 47, September 2011, pp. 76-84)

Sandwiched between Dandelion Days and The Dream of Fair Women, this collection of sixteen vivid short stories, or nature essays, includes tales of badger, raven, swallows, foxes, owls, humans, a mouse, a weed, and peregrine falcons. These stories portray nature with a stark realism, natural life as it really is (the aphorism ‘red in tooth and claw’ applies) but also with a tender, lyrical insight. Some of the stories involve humans in all their strength and weakness, nobility and wretchedness. In fact HW hardly differentiates between human and animal in these portraits of the natural scene.

As with The Lone Swallows, several of the stories had already appeared in magazines in this country and the USA. HW’s ‘Richard Jefferies Journal’ records within an entry for 8 April 1922 (the first for nearly a year):

I tried my hand at animal stories at Christmas – chiefly because Dakers pressed me to – with the result that I have placed

“Bloody Bill Brock” and “Zoë” with Pearson’s magazine.

Wade, the editor, took me to the Savage Club; he is a charming fellow.

“Li’l Jearge” with the royal Magazine

“Aliens” (a tale of Lewisham) with Cassell’s.

(Dakers was his agent Andrew Dakers, a man at all times supportive, tactful, gently chiding, guiding – and very good at his job. HW was very lucky that he found from the start such an empathetic person to take on his work.)

In the later Collected Nature Stories (Macdonald, 1970), a volume which contains an admixture of stories from these early volumes, HW wrote that he was able to write these stories after the departure of ‘Julian Warbeck’ (in real life named Frank Davis). The sojourn of this wild Swinburnian gentleman at Skirr Cottage no doubt also accounts for that long gap in the ‘Richard Jefferies Journal’! Julian Warbeck appears in both The Flax of Dream and A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight series of novels, and HW would have expected his readers to recognise that otherwise rather obscure 1970 reference to him.

With some peace now, I put aside Dandelion Days, and began to write a story, based on a walk during the winter of 1919/1920 to see a friend who lived near Dartmoor.

That story is ‘A Winter’s Tale’, but it is not in The Peregrine’s Saga and did not appear in print for many years, until Tales of Moorland and Estuary (1953).

One of the notable features about the production of this first edition is the number of blank pages, nearly always three of them, on one of which is printed the following title, between each story. A luxury not afforded by today’s costs of paper and printing! I have left these blank pages out in my pagination for the various stories.

The first edition was illustrated by Warwick Reynolds (1880–1926), who provided drawings for four of the first five stories. (They are reproduced below.) The illustrations are tipped in, and one wonders why more weren't provided, to give a better balance of illustrations throughout the book. The frontispiece, showing Chakchek, was also used on the dust wrapper. Reynolds had started his career as an illustrator for magazines and comics, and was particularly interested in drawing and painting animals; he had made a study of the animals in the Zoological Society's collection during 1895–1901. He illustrated numerous books on wildlife subjects. Reynolds married Mary Kincaid, daughter of a master printer, in 1906, and they settled in Glasgow, apart from a year he spent in Paris, where he studied at Julian's and produced pastel street scenes. He died in Glasgow on 15 December 1926.

Reynolds had come to HW’s attention when he illustrated the story 'Raskil the Wood Rogue' when it was first published in Pan Fiction in 1922, but whether it was HW or the publisher who suggested that Reynolds provide the drawings for The Peregrine’s Saga is not known.

The ambiance of the style reminds one of ancient tales – told by a seer: there is a distinct feeling of ‘Gather round ye people, I am the Storyteller’. (Storytellers in the earliest days of man had a position of great importance.)

The book opens with The Saga of Chakcheck the One-eyed (PS 1923, pp. 1-19), a peregrine falcon blinded in one eye, but gallantly managing to survive:

This tiercel, or male, peregrine falcon . . . head of the ancient and noble house of Chakchek, haughtiest falcons in the West Country.

The tale tells of the courtship of two peregrine falcons in fine detail. Daily they catch pigeons over Scarnell Court, home of Sir Godfrey Crawdelhook, a nasty character who determines to kill them. Having no success, he eventually tethers a pigeon laced with strychnine poison on his extensive lawn. The female falcon cannot resist the fluttering creature, catches it, eats it, and is poisoned to death. Sir Godfrey lays her in his conservatory. Chakchek, in trying to get to his mate, is imprisoned within it and is stunned with a whack from Sir Godfrey’s tennis racket (the scene is a pastiche of ancient jousting rites) and – not openly stated – blinded in his other eye with a knife. Crawdelhook cruelly lets him go. Blinded, it instinctively flies upwards until its strength gives out and it falls out of the sky on to ‘Santon Burrows’. As the house and its owner would possibly have been recognisable (Tony Evans, HWS expert on HW’s ‘West Country’ writings, ascribes it to Sir William Williams of Upcott House near Barnstaple), one feels HW was lucky not to have a lawsuit on his hands!

The story first appeared in Hutchinson's Magazine in April 1922. HW noted on 27 April: ‘Rec’d 500 dollars from U.S. for “Chakchek” (less commission).’

The next story is Bloody Bill Brock (PS 1923, pp. 23-38). First published in Pearson’s Magazine, HW noted a cheque for £18/18/- (18 guineas) received 21 February 1922; and further, on 15 December 1922, ‘World Fiction U.S.A., s.r. of Bill Brock - £14/15/- ‘. (s.r. is probably ‘serial rights’). This story was very popular and appeared in various magazines.

Li’l Jearge (PS 1923, pp. 4-57) (Retitled The Mouse in later editions) was first published in the Royal Magazine in February 1922. HW’s diary entry for 21 February notes: ‘£18/18/-‘. The story concerns ‘Uncle Joe’, ‘Granfer Jearge’ and ‘Ernie’, all based on real village people of that time. Granfer Jearge has been deemed ‘incapable’ and is to be put into ‘the Grubber’, the workhouse at Barnstaple. (That was a fate worse than death to anyone condemned to it.) As he feeds and talks to the rats and his pet mouse, ‘Li’l Jearge’, he begs the good lord that he will die that night. But next morning, he comes out without a word, and gets into the jingle cart with his precious ragged belongings. He then does not move or speak to any of those gathered to say goodbye. ‘Li’l Jearge’ climbs out of his pocket on to his shoulder, but gets knocked off and is killed on the road; its baby mice are killed as well. Still Granfer Jearge neither moves nor speaks. For Granfer Jearge has died at the moment of getting into the jingle. He is carried back into his cottage and laid out on the table. The rats come out at night, but at the sight of the old man quickly disappear back into their tunnel: ‘passing the brown mummy with its curled teeth and hairless tail crouched in still attitude on the ageless dust.’

The latter creature really was found in a wall cavity at some point, and HW preserved a photograph of it:

HW wrote on the back of this photo:

Note the tail of extraordinary length. This is the dead rat that suggested parts of “Li’l Jearge”. I think it must have been poisoned by arsenic ages ago, which has preserved the leather of its body. The teeth, as can be seen, have grown after death. This is of immense interest to natural science, & is the only case on record, I believe. The rat was found in an old condemned cottage wall in Appledore Village, North Devon. Henry Williamson.

The Bottle Birds (PS 1923, pp. 61-76) – in the 1934 edition this was retitled The Air Gipsies. These birds are long-tailed tits, with their ‘sisisee’ call. Their nest is bottle-shaped – a 9-inch long oval shape with a small entrance hole.

Every day a bearded man, passing down the hedge between the nettles and the green wheat, stopped in slow meditation and parted the branches . . .

(Note that at this time HW had grown a beard!) Sisisee and her mate patiently build their nest of lichens lined with feathers (there is reckoned to be 2000 feathers in a single nest), but they are watched by the Butcher Bird, or Red-backed Shrike, who waits for the most opportune moment to rob the nest and eat the young, spearing one on a thorn as a larder for later. Sisisee's mate later pairs off with Jea, who had shared their nest, while Sisisee and Jikky Jikky Oneleg eventually go on to make a new nest, and the following year successfully bring off a family.

Zoë (PS 1923, pp. 79-99) first appeared in Pearson’s Magazine under the title ‘The Man Who Did Not Hunt’. (Two pages of this were found in the archive and printed in facsimile in HWSJ 31, September 1995, pp.71-3, at which time the attribution was not known.) HW again noted £18/18/- paid. That original story was much revised for this book. Another tale involving the cruelty of Sir Godfrey Crawdelhook, ‘Zoë’ tells the story of Captain Horton-Wickham, badly injured in the First World War, and his love of otters. He rescues an infant after its mother has been wantonly killed by Sir Godfrey. He takes the cub to the local pub (The Foxhunter, its real name, which HW knew well), where it is fostered by an old cat, Teeter, and thrives. But inevitably there is an otter hunt and Zoë is killed, held by the Captain to whom she has run for shelter. The hunt followers watch aghast as there is a gun-shot: the Captain has killed himself. One of these followers is ‘Diana Shelley’ (the red-haired Lois Martin, the supposed dedicatee of The Lone Swallows) and at the end appear Mrs Ogilvie and her daughter Mary and Howard de Wychehalse, who are main characters in The Pathway (then not written, but very evidently already well thought out). HW gives an interesting twist at the end of his tale, but you will need to read it for yourself to discover what it is! The story is the forerunner of Tarka the Otter, and the basis for HW’s tale that he had rescued an otter cub. A tiny note in a much later diary (1941) reveals that Captain Horton-Wickham was a real man, and had indeed rescued an otter cub; that HW had been friends with him at that time, and had certainly shared in looking after the creature.

Raskil the Wood Rogue, dedicated ‘(for Edward)’ (PS 1923, pp. 103-117): in the 1934 ‘Tunnicliffe’ edition retitled The Wood Rogue. HW noted in his 1922 diary: 23 September, ‘From “Pan” [Pan Fiction] for “Raskil”, less 10%, £15/15/-‘, and on 21 November, ‘Rec’d from “World’s Fiction” USA s.r. for ‘Raskil’ £14/5/-‘ The dedicatee is Edward Graham Stokes (brother of Mary – ‘Annabelle’ of The Sun in the Sands) who, aged 11 at that time, was a devoted shadow of HW (see Edward Stokes, ‘The Owl Club’, HWSJ 47, September 2011, pp. 76-84) There are one or two charming little notes from him in the archive, one signed ‘Rdwurkr’ (see below). Edward became a commander in the Royal Navy, and author of two important books on ocean birds.

One might think that Raskil would be a weasel but in fact he is a rook of the great ‘Rookhurst Wood’ colony – and his father’s name is ‘Rdwurkr’ (hence Edward’s signature!). The story involves their adventures in life, one of which involves ‘Willie and Jack’ (Willie Maddison and his friend Jack Temperley from the early Flax of Dream volumes). Raskil was ‘dangerous to old Bob Lewis, the keeper to Squire Tetley’ (again both from Flax, and of course based on real people). Bob sets a trap and Raskil is caught and killed, and hung on ‘the gallows-tree of the failures, of the wood rogues . . .’. The story ends with philosophical acceptance of inevitable death.

All were merged into the earth which embraces with tranquillity the forms of those who, after toil and endeavour, are discarded by the spirit. Sun and wind and rain attend the inexplicable comings and goings of bud and leaf, of egg and bird, or babe and parent. After toil and endeavour there was equal rest for Rdwurkr and Raskil.

Redeye, dedicated ‘(for Garry)’ (PS 1923, pp. 121-150). This story opens with tribute to ‘Old Muggy Smith’ (John Smith, previously part of the ‘Tiger’s Teeth’ tale in The Lone Swallows): ‘the most honest man in the village, and one of the rare human beings in North Devon who refuses to repeat or listen to scandal.’ Redeye is a lurcher, owned by Tom Fitchey, which ‘by being brutal to the dog when it was young, Tom had made it brutal.’ (Note HW’s ‘education’ theme there.) Incidentally, ‘fitch’ is a country name for a weasel. In the middle of the story enters, exhausted after a day’s hunting, ‘Sub-Lieutenant Graham, R.N.’. This is Graham Stokes, born 1902, oldest son of Esther, older brother of Mary and Edward – the dedicatee ‘Garry’. Graham, at this time indeed away training for the Navy, later became a rear-admiral.

In this story Sub-Lt Graham has taken part in a fox hunt that day. We meet, as members of the Hunt, a lad named Edward, a beautiful girl called Diana, and a dark, slim, brown-eyed Mary (our Flax of Dream characters again) and various members of the Hunt whom are recognisable as real local people. The fox goes to earth, but when it eventually emerges it is realised it is not a fox, but Redeye. The pack of hounds gives chase, and the story follows this – until eventually Redeye seeks sanctuary at the Crow Inn, where his owner and young Sub-Lt Graham and others are drinking. Tom Fitchey slams the door against the pack of hounds but Redeye never moves and slowly keels over – his heart burst from his tremendous run.

Sirius, that great star-hound of the winter heavens, woke and yawned silver in his kennel of evening-blue space. Dusk came, and the mighty Dogstar broke the chain of day, and gave tongue in green music, and glared fire i’ th’ eye and bounded after Orion, and together they began the hunt of strange spirits over the horizon of time, where no mortal may follow.

This is a tremendous tale – written by a man who is now a master of the writing craft – and a very obvious forerunner of Tarka the Otter.

A Weed’s Tale (PS 1923, pp. 153-170): a seed falls to the ground from a twig carried by a rook. ‘An old man, a little boy, and a seed, these are the characters of the story.’ The old man is Uncle Joe (Joseph Rush, the retired railway porter); the seed is of Rumex sanguineous, or Bloody-veined dock, belonging to the sorrel family, common weeds of the countryside; the little boy is ‘Ernie, and he was four years old’ with ‘sensitive mouth, large brown eyes, and golden curls’ (HW’s small neighbour, the subject of ‘Ernie’ in The Lone Swallows.)

The seed takes root next to Uncle Joe’s boot-scraper: every year it tries to grow and make its own seed; every year Joe cuts it back, to no avail. Finally, he resorts to paraffin. We read of the hot year of drought (1921 summer), and the bolt of lightning and tremendous storm that ended it. A week later Joe was found ‘fully dressed but for his boots, dead in his bed’. The storm rain and lack of Joe’s attention allows the dock-weed a last chance, and although terribly stunted it seeds, and then also dies. But at harvest festival time the following year on Uncle Joe’s grave were found growing ‘a score of young plants of Rumex sanguineous.’

Elegies Three – biographical vignettes of ‘Reynard’ (PS 1923, pp. 173-176) , a fox, death of; ‘Corp’ (PS 1923, pp. 177-8), a pig, runt of the litter, death of; ‘Nor’ (PS 1923, pp. 179-80), a field mouse, death of.

Aliens (PS 1923, pp. 183-99): HW’s 1922 diary notes: ‘Cassell’s for “Aliens” less commission £18/18/-‘. Set in his home area of Lewisham, south-east London, the story involves ‘a black rat, the last of its kind remaining in the south-east of London. For years it had lived by the banks of the Ravensbourne stream.’ We are told it is ‘The drama of Tattered Joe’ (a man with hair like an over-ripe banana skin and face a rotten squashed apple); ‘of Slimey, the last black rat’, ‘Splitail, the last fish [a large roach] . . . dead-and-alive, in the stream . . . an animated corpse’ and ‘a boy’. The boy’s name is Phillip, who has a cousin Willie who lives in the country (the Maddison cousins in The Flax of Dream and A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight). But we also have an officer on leave, by the name of Maddison, and we learn about food shortage during the war in Lewisham. Thus we have what is possibly a prequel to A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight!

The climax of the story is that the rat, creeping to get some rancid meat out of Joe’s pocket, is caught by an owl; but in the ensuing struggle between the two creatures, Joe awakes and kills both owl and rat. Then, shortly after, in the hard winter of 1917, Tattered Joe is found ‘lying frozen in the old heap of sedges and sticks, his heart pierced by the black frost of that tragic year.’

The Chronicle of Halbert and Znarr ‘(for Tubby)’ (PS 1923, pp. 201-228) (the identity of Tubby is unknown). Halbert (p. 201-215) is a London urchin who wanted to go into the countryside and get an armful of bluebells (thus harking back to ‘London Children and Wild Flowers’ of The Lone Swallows), and the tale tells of his adventures: starting with getting a lift in a racing car to Southend Pond, because the car nearly hits him and Halbert knows how to milk a situation! He dares himself to climb up and get a newly-hatched carrion crow nestling, but then puts ‘the blasted chicken’ in a thrush’s nest with two nestlings – but one of them is a cuckoo! The carrion crow nestling ousts both other birds (an unusual twist, as it is normally the cuckoo which is the villain of such situations). Halbert is given the chance to better himself by the owners of the racing car.

Znarr (pp. 216-228) is the tale of the carrion crow nestling that Halbert puts into the thrush’s nest. Znarr was the biggest and strongest and was able to grab all the food brought by the adult thrushes, and the thrush and cuckoo nestlings soon die. Znarr grows and, thrashing around, destroys the nest and is then caught again by none other than young Halbert, out with others (including the bully Winking Wooldridge) for another day in the country. He takes the terrified bird back with him, leaving it at the Elephant and Castle with his mother and crippled sister. Halbert goes off to his new job as ‘Albert’, pantry boy on probation to Sir John Lorayne (a character who appears in The Dream of Fair Women). Znarr blinds the eye of the bully, ‘Winking’ Wooldridge, and becomes an ‘outlaw’.

Halbert loses his position as ‘pantry boy (the butler reports he is ‘incorrigible’!) and returns to the Elephant and Castle to his old newspaper selling pitch. On his way home he sees Znarr flying away, never to be seen again. ‘Winking Wooldridge’, though now blind it one eye (we read that it had at least cured the ‘winking’ problem!) becomes a promising boxer known as ‘Lord Nelson’. He and Halbert become friends: ‘Halbert' and 'Oratio’ – an amusing ‘pun’, and a rare happy ending.

Bluemantle (PS 1923, pp. 231-38) is another tale about a pair of swallows set on the moorland behind the dunes (of Braunton Burrows) who mate and make their nest in a cattle shippen in the village where the female lays her eggs. But a small boy takes the eggs – and a further nest is ruined. Then the birds make their nest in a ruined cottage [possibly that which had belonged to Granfer Jearge] but it is late in the season – it is mid-September when the eggs hatch. The time comes for migration south, but the nestlings cannot yet fly: the parents, obeying their innate instinct, leave –

‘For life has its claim even as death has its toll . . .’

Unknown (PS 1923, pp. 241-51): ‘A Tale for the Fireside when Holding Hands’. A storm is presaged: striking similes are clouds as ‘swart impis’ (Zulu warriors) and lightning an ‘assegai’ (African spear). This is the storm that ended the long drought of the 1921 summer. The narrator (‘I’ equates to HW) shelters in a derelict cottage; his dog refuses to enter, but he throws it inside. The atmosphere is extremely mournful. Eventually, with difficulty, he gets a fire going and then falls asleep and seems to dream, seeing grey shadowy figures. The dog is terrified and jumps out through the window. He leaves and gets to the inn down in the hamlet. After two glasses of rum, the landlord tells him that the last tenant (of the ruined cottage) was near 100 years old and had lived there with six dogs. When he was found dead, the dogs were fiercely guarding their master and had had to be poisoned. He puzzles over this:

‘Of what importance was the world of matter regarded in the light of dream and imagination – of the soul?’

After talking to a white witch, who explains ghosts to him, he goes to Lydford Gorge (near Tavistock on the western side of Dartmoor, Devon) and ponders reincarnation.

Have I been all the time, in a hundred different forms, each one evolving higher to the godhead of perfection, to discarnate, timeless omnexistence?

But he is calmed by the natural life around him.

Many such turbulent imponderables exist in HW’s ‘Richard Jefferies Journal’. His book The Star-born, set in Lydford Gorge – and actually written at this time (1922) – is his attempt to answer these metaphysical questions.

The Meal (PS 1923, pp. 255-60) tells the tale of two men who imprison a fox in its earth. They cannot then agree whether it is actually there or not, as no tell-tale signs appear even after two or three days. So they shoot a rabbit and leave it inside. It is not eaten, so they unblock the earth – and as they disappear on their way home, a starving thirsty fox emerges and gets a drink from rank pool and then eats the rabbit. This shows the cleverness and cunning of the fox, and is a sort of ‘Brer Fox’ story in reverse.

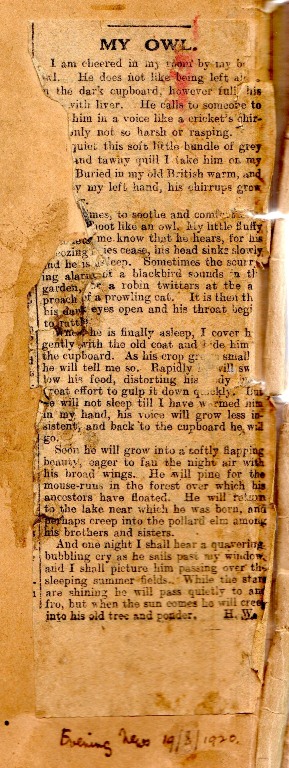

A London Owl (PS 1923, pp. 263-73). This is an expanded story of a very early (almost the first) published item, ‘My Owl’, which appeared in the Evening News, 19 August 1920, and is pasted on to the front cover of HW’s ‘Richard Jefferies Journal’. It is based on a true event in HW’s life.

(There is an illustration of the front cover to HW's 'Richard Jefferies Journal' after the Critical reception section.)

The narrator ‘I’ is writing about ‘the last meeting of Jim Holloman and Dolly in the spinney I was remembering from boyhood’, and watching for the owl’s nightly visit. This is HW writing the climactic scene of his first book The Beautiful Years, while still living in his parent’s home in Eastern Road, Lewisham, south-east London.

In those days, worn mentally with the terrible war and the terrible peace, I did not think I would live much longer.

(‘In those days’: that was 1920, and at the time he was writing this piece it was no later than early 1922! So much has he changed and achieved in that short period.)

In the story, he is told by a man whose garden is nearby that the owls’ nest is in a tree which is about to be felled because it is dangerous, and he is invited to save the two owlets: one survives, and we read of its upbringing. Eventually grown enough to fly, he frees the bird, but it is captured by the rag-and-bone man. He finds it, buys it back – sets it free, and after a few hours it flies off. In HW's earliest photograph album there is a tiny photo (one inch square) of that surviving owlet sitting on a tree stump, which enlarges remarkably well:

The Saga of Mousing Keekee (PS 1923, pp. 277-301) opens:

Far away over the western sea a star flickered, like a gold falcon flying in the dark. Perhaps it was the god of all hawks . . . The star hung over Lundy Island . . . the flickering fold of its flashes seemed to be tremble and beat like the wings of a faithful guardian watching in the night.

It must surely send a shock through all HW readers to make a connection there with his book The Gold Falcon, the story of his 1930/31 adventures in America, published in 1933 – ten years in the future.

This is the tale of the orphan nestlings (Wizzle and his sister) of Chakchek the peregrine and his mate, who were killed by the particularly unpleasant Sir Godfrey Crawdelhook. Mousing Keekee is a kestrel who has lost her own brood of chicks. She discovers the peregrine chicks on a cliff ledge desperately calling for food from the parents who can never return, and catches a rabbit, brings it to them, and continues to feed them, though not to brood them. This work is so demanding that she begins to deteriorate.

But Keekee never failed. She was female. She worked for little ones.

However Keekee is attacked, and her leg badly injured by Swagdagger the stoat (later himself killed by Kronk the raven). She is now very weak, and unable to hunt. Now the mood twists and we have Tiger (fisherman and blacksmith – as in the ‘Tiger’s Teeth’ story in The Lone Swallows) and a younger man, Howard, out getting ‘lanners’ – young peregrines – off the cliff face. (There is a character called Howard de Wychehalse in The Pathway, admirer of Mary Ogilvie.) Despite his fears Howard manages to get onto the ledge where the peregrine chicks are, where he smokes a pipe to calm himself before taking the tiercel, leaving behind the falcon. During this time Keekee stands off, helpless, just watching. As Howard makes the rather perilous journey back up the cliff, the buzzard, Mewliboy, wails ‘finish, finish’.

These are the words HW used at the end of his Schoolboy’s Nature Diary notes: ‘And Finish, Finish, Finish, the hope and illusion of youth, for ever, and for ever, and for ever’, which must have been in his mind as he wrote that. Although those poignant words were not known until they appeared in my HW biography Henry Williamson: Tarka and the Last Romantic (1995), and would therefore have had no significance to readers then, the use of them here obviously had great meaning for HW himself.

Then high in the west, a faint point of light, he saw the star of all the falcons. It became brighter, and beat sharp wings as it hovered, protecting, in the evening sky. . . .

The night passed, and steadfastly the star hovered, flickering gold wings in the west. Its wings were poised to heaven, then slowly drawn down and folded round its gold, immortal body. It was very far away. The waves broke on the rocks, rushing in white foam, lapsing, and rushing again. The star was gone.

Keekee is dead, brooding for the first time, the fledgling peregrines:

They were happy, they were flying, they were with the star.

Again these images are reiterated in the later novel The Gold Falcon.

*************************

I think one can say that it is in this book, his fourth, that we can recognise that HW came into his own as a writer. It is very noticeable that the overwhelming content of nearly all the stories end with death. Somehow, though, death is not the end, or at least not in itself. There is a philosophical acceptance of death as the end of life’s cycle, and the merest hint that all life becomes transformed into ‘other’ – a spirit that joins that ancient sunlight that was such an important feature of HW’s belief, and an aspect explored in his book The Star-born, which though published in 1933 was actually written in 1922 – the same period as these stories.

This concentration on death has to have been, even if HW did not realise it himself, a cathartic cleansing of his mind and spirit of the horror of the meaningless violent deaths that he had experienced in the recent Great War. It makes these early short-story volumes of great importance, not just for their intrinsic content or for their part in HW’s development as a writer, but as a metaphor for, and perhaps one could say as a memorial to, the dead of the war.

*************************

As with The Lone Swallows, further editions of The Peregrine’s Saga became complicated and some explanation is necessary (see Matthews’ Henry Williamson: A Bibliography for full details).

In 1925 the book became the second of HW’s titles to be published by Dutton in the USA under the title of Sun Brothers, a lovely title choice (there is no subtitle, perhaps because the subtitle given The Peregrine’s Saga in the UK – ‘And Other Stories of the Country Green’ – had been used by Dutton for their edition of The Lone Swallows). The cover is a pastoral scene in rather muted shades of green. The stories are the same, but ‘Li’l Jearge’ and ‘Red-eye’ are moved to the front. As with their edition of The Lone Swallows, each story opens with a dropped capital letter (this time not enclosed or attributed), which is decorated with sketch of the creature within that story. Unusual words are given a very short footnote explanation for their American readers.

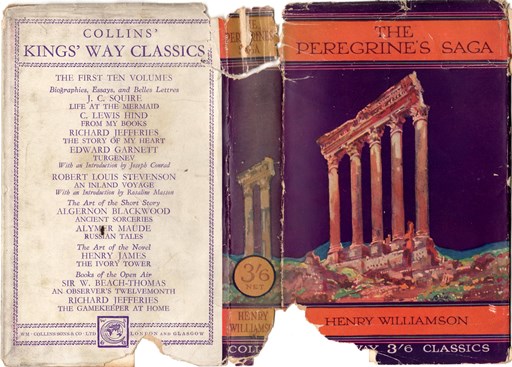

Collins published reprints in 1927 (Kings’ Way Classics) and 1929 (Pocket Novels), but they objected to the revisions that HW wanted. One must remember that this involved ‘hard type’ setting, and alterations were very costly. All publishers must have found HW’s continuous revisions quite a nightmare to deal with! He had anyway decided that he had outgrown Collins, and was actually negotiating with Putnam over future titles. That this was all somewhat acrimonious is shown by letters in the business files. HW often upset publishers by constant interference in the business negotiations.

In February 1934, Putnam (by then having published Tarka the Otter and enjoyed its success) published a new edition to match a uniform set, including the new illustrated Tarka, of the ‘nature’ books: all of which were illustrated by Charles F. Tunnicliffe. There were, of course, new revisions. Now subtitled ‘and Other Wild Tales’, there were also some story title changes: ‘Li’l Jearge’ is sadly demoted to ‘The Mouse’, but ‘The Bottle Birds’ to the better ‘The Air Gipsies’. Some stories were incorporated from The Old Stag (Putnam, 1926 – the first book by HW that Putnam had published) and there are now five peregrine stories altogether (two from the original edition, two from The Old Stag, and one which had previously been printed in both Harper’s and The Windsor magazines, but retitled here). There were several reprints of this edition, particularly in the late 1940s, a turbulent period in HW’s life and a lean period in his writing, and so a useful source of income.

These stories were given a fresh airing in the two collected compendiums published by Macdonald: the actual ‘Peregrine Saga’ stories into The Henry Williamson Animal Saga (1960) and the others in Collected Nature Stories (1970). Then in 1982 Macdonald published a paperback edition of The Peregrine’s Saga in their Futura series. Taken from the text in Collected Nature Stories, this rather unfortunately does not contain any ‘peregrine's saga’ stories. One wonders what new readers made of that! The blurb of this edition calls HW: ‘The last great visionary of his generation, a man much loved, much misunderstood, and a writer by turns neglected and famous. . . .’

*************************

As with The Lone Swallows, there is very little evidence of reviews of the first edition in the archive, but a small number of extracts are quoted on the front inside flap of the American edition (see illustration below). Retitled Sun Brothers, it was the second of HW’s books to be published in the US, in 1925, coming after The Dream of Fair Women (vol. III of The Flax of Dream), and this is reflected in the reviews. HW is still a ‘new boy’. Again the review source, written in green ink on thick dark brown (scrapbook) paper, has rendered some illegible.

Herald, Boston, 24 June 1925:

Henry Williamson’s “Sun Brothers” is a rare book for nature lovers. They will welcome its author to the small and famous company of the men who have loved wild places and wild things so deeply they could write about them in words that enchant and live. Mr. Williamson will be remembered for his first book “A Dream of Fair Women” . . . This new volume, a collection of 16 sketches . . . In every one of the chronicles there is a drama and into each one the human element enters and is closely interwound with the fate of bird, or beast, or plant. Pathos, tragedy, humor now and then . . . extensive and accurate knowledge of nature and her ways.

Lancet, Salem, Oregon, September 1925:

“Sun Brothers” by Henry Williamson, author of “The Dream of Fair Women” . . . Most beautiful human-interest and animal-life story of the year. The author has capitalized loving-kindness and the humbler-heaven on earth in the form of literature from the viewpoint of life in North Devon, England. We enter into the life of the poor, their loves and affection for the simpler and littler creatures, both tame and wild, their sorrows and their tragedies . . . The denizens of the humbler cottages, the wayside loafer in the pothouses, the slinking poacher, the hanger-on at the fox-hunt are all given sympathetic interest . . . It is a jewel of a book.

Tribune, New York, 14 June 1925, headed ‘Beasts and Men’:

Many people remember Mr. Williamson’s first book . . . His new book . . . only mildly sentimental, at times too obviously ironical, but which for the most part read like authentic tales.

He uses in his framework, as well as in each incident, the hopelessly cruel plan of nature dominated by the instinct for self-preservation and he describes it with the savage detachment of one who has been tortured into passivity, who must accept these tragedies if he desires to live. . . . He sees clearly that man is controlled by the same ruthless and relentless forces that control the animals.

Argonaut (A.W.), San Francisco, 30 May 1925:

Mr. Henry Williamson’s “Sun Brothers” are Devon wood folk, badgers, otters, weasels, and even a bird or two. These “little brothers”, in the Franciscan phrase, are unromantically termed “vermin” by their enemies . . . These stories are beautifully written in a style admirable suited to the theme . . . considered solely as short stories they are excellent. Not one savours of the pot-boiler variety. If “Sun Brothers” meets with the success it deserves, it will be a “best-seller”.

Journal of Commerce, Chicago, 17 June 1925:

And finally, in order to make this week’s list of books perfectly democratic there is a collection of animal stories by Henry Williamson called “Sun Brothers” that is as beautiful and as sympathetic a thing as has ever been done in its way . . . It deserves unstinted praise and enthusiasm.

Eagle (Marion Leland), 5 December 1925 (7-inch column), headed ‘BROTHERS OF SOL’:

“Sun Brothers”. Is the title of this volume ironic like so much in the 18 terse tales grouped under it? [‘Elegies’ is sub-split into 3 separate titles in the U.S. edition giving an extra number of stories] Or is it a happy suggestion of a common heritage?

Without bitterness of word but with all the concentrated force of life’s dramatic ironies, Henry Williamson prods the quick in these vignettes of some of earth’s hunting and hunted . . . He writes with the stern candour revealing the glare of midday sun. [VERY percipient] . . .

This quivering sensitive young author, reaching to the unanswerable enigmas of death and pain . . . Mr Williamson uses a sharp scalpel and does not hesitate to scrape the bone to the marrow. However, like a proper artist, he lets in . . . the joy of living. With the lyric lucidity of his diction and his vision they balance the shadows in his chiaroscouros. . . .

[Unknown source] (Marion Storm), New York, 27 June 1925 (10½-inch column):

This is the most catholic book of life, a chronicle of weeds and falcons, of swallows, street urchins, ghosts, foxes and old men. Mr. Williamson’s spirit is a harp upon which faint winds strike deep chords . . . He has a power of sadness which is rarely encountered in literature. It is beyond sentiment, severely mournful as an autumn afternoon, achieving heights of tragedy through simple accuracy . . . The style . . . is poetical without deserting the meet realm of prose.

One or two reviewers point out, as being irritating, HW’s habit of transposing words within a sentence, so making them awkward.

New York Evening Post (H.B.), 27 May 1925 (16-inch column):

[introductory paragraph] . . . Mr Williamson draws his Devonshire peasants and his London street children with equal skill and truth. His stories are tragic without exception; nature smiles but seldom for those who look beneath her mask of beauty . . . Mr Williamson’s animals are not falsified . . . he makes them very real and very appealing and highly individualised . . . His title is fully significant; he thinks of bird and beast as brothers under the sun and tells of their joys and sorrows as tenderly but at the same time as accurately as anyone could ask.

Mr Williamson writes extraordinarily well. His style is lucid, instinct with beauty, often highly poetical, with no sacrifice of strength not the slightest feeling of a straining after effect. His is a sensitive spirit able to express itself sensitively. . . .

Here’s a book to satisfy lovers of good writing who also know and love woods and fields and the denizens thereof . . . Mr Williamson is a person worth watching.

Chicago W. Post (W.G.), 26 June 1925 (10-inch column):

Stories of falcons [etcetera] . . . there will be . . . a feeling of having met reality in natural life, a reality and beauty common in the writing of W. H. Hudson. Back of the simplicity and hardiness in Williamson’s stories can be sensed the intangible relationships in the animal world. At times it is almost mystical . . . There is in the writing of all the pieces a restraint, an abstaining from sentimentalism . . .

The Bookman, in the UK,in its traditional lavishly illustrated bumper Christmas issue for 1923, carried both a Collins' advertisement for the book, and a sympathetic and positive review:

It is obvious that these stories merit an attention possibly not engendered in recent years. They have their own intrinsic value, but they also have great importance in underpinning the tower of HW’s total oeuvre. They form the all-important corner-stone. Unfortunately some of their import is lost in the later editions, when the mix of stories changes, so diffusing the clarity of essence which stands out so very clearly here.

*************************

The cover of Henry Williamson's 'Richard Jefferies' Journal:

*************************

The dust wrapper of the first edition, Collins, 1923:

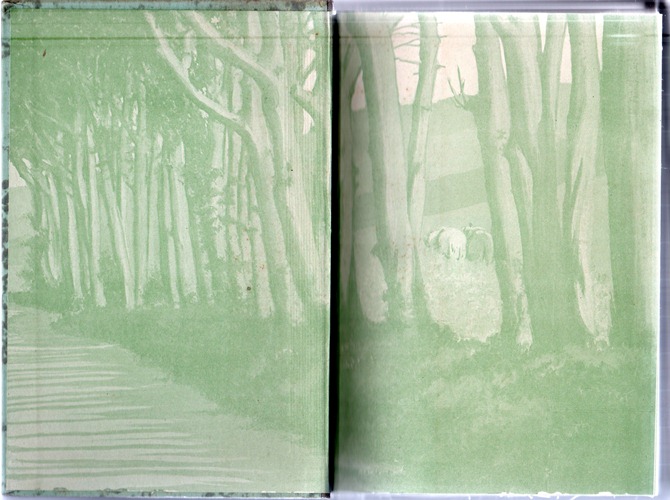

The dust wrapper and end papers of the first US edition, Dutton, 1925:

The dustwrapper of the Collins 'Kings' Way Classics' edition [1928] (note the error in the listings – 'Henry T. Williamson'!):

Collins also offered their 'Kings' Way Classics' in another style of dust wrapper:

The spine and front of the Collins 'Pocket Novels' edition [1929], with HW's facsimile signature imprinted on the front:

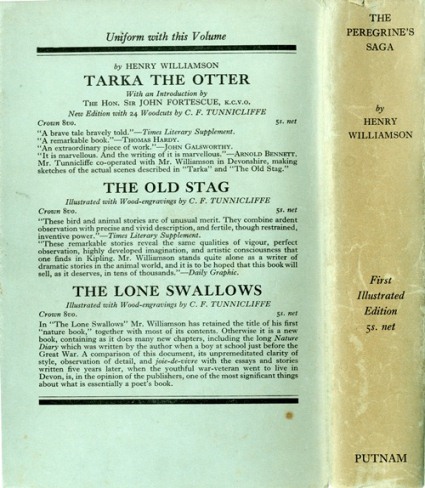

The dust wrapper of the scarce first illustrated edition, Putnam, February 1934, published at five shillings:

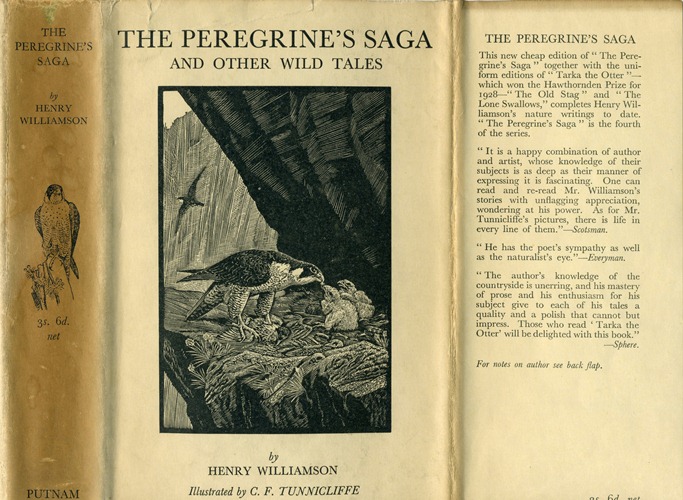

The dust wrapper of the more common illustrated cheaper edition, 1934, published at 3s 6d (often wrongly described and sold as the first illustrated edition):

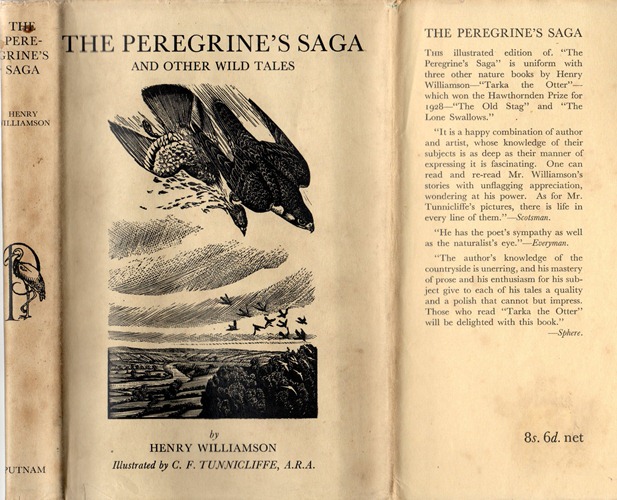

The dust wrapper of the later, 1945 post-war edition – a slimmer volume (it was printed on cheaper, thinner war economy paper), now priced at 8s 6d:

Macdonald's Futura paperback edition, 1982, £1.50; although it features an attractive wraparound cover painting (the artist is unidentified and there is no acknowledgement), it is unfortunately conspicuous for its lack of stories about peregrines!:

************************

Back to 'A Life's Work' Back to 'The Lone Swallows' Forward to 'The Old Stag'