THE ACKYMALS

|

|

| The Windsor Press, 1929 |

'The Ackymals' (The London Mercury, Jan. 1927)

The Windsor Press, San Francisco, Autumn* 1929 ($7.50)

Limited edition of 225 'boxed' copies (i.e. within a cardboard slip-case)

(* a letter from The Windsor Press dated 19 August 1929 states 'We expect to have the book completed within the next two months . . .' - thus making publication mid October.)

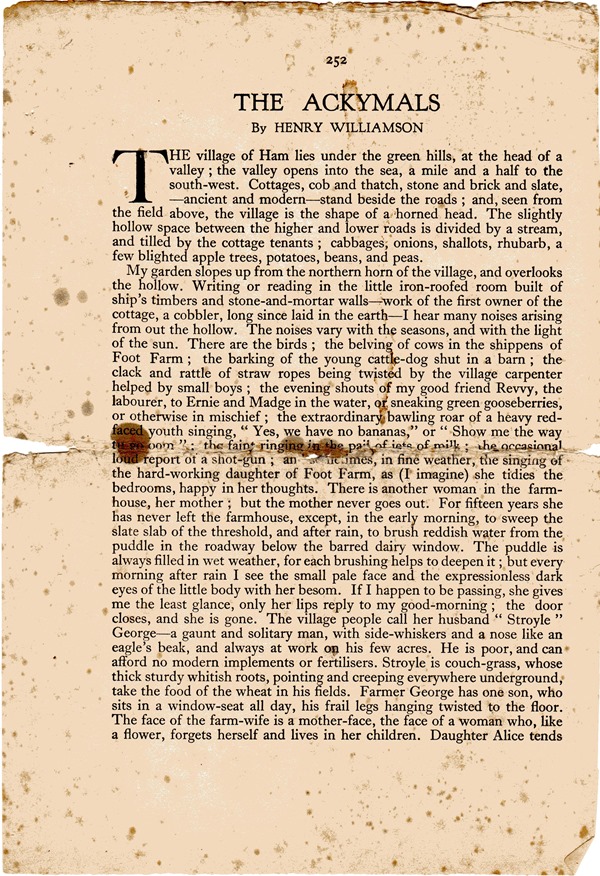

The Ackymals first appeared in The London Mercury, January 1927. This prestigious literary journal was instigated in 1919 and edited by Jack (John) Squire (he was knighted in 1933), who was so influential in awarding the Hawthornden Prize to Tarka the Otter and HW. Clearly written in 1926, The Ackymals should therefore be considered as part of the early short stories – and again it has death as a chief concern.

The story is a vignette of village life, based as much on the scenes surrounding the tragic death of a baby as on that of the central story of the shooting of ‘ackymals’ by John Kift, who wrongly, but doggedly, maintains that they eat his precious peas.

The term ‘ackymals’ (a Devonshire dialect word), also referred to here as ‘tomtits’, was explained by HW in a letter (dated February 1928) printed in The London Mercury with reference to various ‘strange’ terms used in Tarka the Otter, as meaning ‘both blue and the great titmouse’. In The Ackymals all four of the common British tits are included: great, blue, coal and marsh; and once the reader has got over the oddity of the title, it is obvious that the writer is talking about these small birds.

The entire story, as printed in The London Mercury, appears later in this page for those who have not read it before – there are some small differences in the Windsor Press edition – but this summary may be found useful. 'The Ackymals' opens by setting the scene with a short (but wholly encapsulating) description of ‘My village’ (very obviously to us, this is Georgeham in North Devon) and then ‘my’ garden and ‘my’ writing room, an ‘iron-roofed gable room’: immediately showing that this is Vale House, into which HW had moved in the late summer of 1925, rather than the original Skirr Cottage which was (and still is) thatched.

|

| Hw, Loetitia and their first-born, Windles, outside Vale House |

Across the road from this writing room was situated ‘Foot Farm’, which was in real life ‘Hole Farm’. The farmer of Foot Farm in the story is ‘Stroyle George’ (actually Farmer Lovering) and there can be no doubt that the portrayal of the characters in this story is extremely accurate. ‘Stroyle’ is a local term for couch grass, a most pernicious weed.

A shot is heard, and hearing young Ernie (the son of HW’s neighbour at Skirr Cottage, and so still a neighbour, as living between the two residences) exclaim, the writer leans out of his window to ask Ernie what was going on, to be told: ‘Tis Janny Kift shooting th’ackymals on his pays!’ Having repeated ‘Janny’s’ violent dislike of the little birds (the repetition of phrases is Ernie’s wont), Ernie informs the writer that the funeral of the dead baby is to be held that afternoon: the writer remembers that he had heard the church bell toll just once (thus for a one-year-old) a few days before.

The writer sets off to remonstrate with John Kift, who lives with his wife beyond ‘The Stag and Tufters’ (what HW was to call ‘The Lower House’ in later books, and was actually The King’s Arms – this name being used in the earlier London Mercury version – situated on the corner of the main village street). The scene in their house is piercingly accurate: amusing, but full of pathos and bathos. Janny Kift is not to be shifted from his views: his wife is anxiously supportive of her husband. The writer asks him to bring him the next birds he kills so that they can be opened up and examined, so proving they contain no peas at all.

On leaving them the writer feels a hypocrite – as he had also killed small creatures (he specifies slugs and snails in this story, but we know that as a lad on holiday visiting his Cousin Charlie at Aspley Guise, Bedfordshire, he quite happily shot small birds, including cole tits). Returning to the street, he realises the funeral procession is approaching the church and moves to one side as they enter. He stands by the wall watching the antics of the village children, who have no cognisance of the tragedy and are getting up to normal childish mischief. The mourners emerge and go to the grave prepared for burial, and the interment proceeds. The children scatter, and grow quiet. A coach full of Welsh miners lustily singing national choruses passes by momentarily drowning out the vicar’s intoning voice: the sad interment proceeds with its platitudes of life everlasting away from the miseries of the world – words that the writer feels somewhat inappropriate for a tiny child who had known no misery.

A family of marsh-tits flitter cheerfully in the leafy branches over the grave, among them a coal-tit: the writer had been watching them for weeks as they flew around the village.

The service over, the sad mourners depart. ‘Then I heard the report of a gun.’ The village children resume their games again. John Kift appears and is amazed at the cost of the flowers by the grave. He produces two dead marsh tits for the writer to examine, still shaking his head at the wasteful cost involved in doctors’ fees and flowers, while the old women shake their heads over the tragedy of death of ‘the poor li’l mite’ who had ‘ate nearly a plateful of tinned salmon’ the night before it died. (The implication is that this is what has caused, or at least hastened, the baby’s death.)

The writer opens up the crops of the marsh tits. There is no sign of peas – only tiny black weed seeds. But John Kift is still convinced that they are the culprits: ‘They ackymals be master rogues for stealin’ pays, and I’ll shute ivry wan I zee!’

*************************

The two strands of the story deftly complement each other to show the unthinking futility of death – coming unexpectedly to annihilate both child and creature. It is a seemingly simple tale, but its hidden depths reveal a most moral purpose. It was certainly written by a master of the craft and is a story that perhaps has not had its proper attention. The truth of its message is eternal. (But one does rather wonder what readers in America made of it all.)

A page of HW's notes for 'The Ackymals':

*************************

San Francisco had become an important centre for printing during the Gold Rush of the mid-nineteenth century, and The Windsor Press were notable printers of what was called ‘the second wave’ period. It was run by James and Cecil Johnson, brothers who originated from Australia. In later years The Windsor Press were official printers for San Francisco University. It finally ceased trading in 1978, but had hit financial problems far earlier than that, as will be seen.

HW was approached by The Windsor Press through a letter signed by Cecil Johnson on 28 March 1929. The letter is wonderfully formal in its content, and after praising HW’s writing sets out the brothers’ terms:

There is no mention of this project by HW, apart from a brief note in his 1929 pocket diary (otherwise almost empty, see AW’s biography Tarka and the Last Romantic, p. 116):

Friday 31 May: Sent The Ackymals to the Windsor Press, 461 Bush St., San Francisco. 225 copies signed, 250 dollars.

Cecil Johnson wrote on 19 June 1929:

In the accounts section at the end of that 1929 pocket diary, HW has noted:

1 July: [received] U.S.A. for ‘Ackymals’ £50.0.9d

(It would seem therefore that the exchange rate at that time was about $5 to £1.)

The Windsor Press wasted no time in issuing a Prospectus for The Ackymals:

The Ackymals was published in the autumn of 1929, so typesetting, printing and binding must have proceeded post haste. It is a handsome production, with cloth-backed decorative boards and thick deckle-edged hand-made paper, the top edge being trimmed. The title page is decorated with a leaf flourish on which sits a bird holding a shield embellished with a ‘W’:

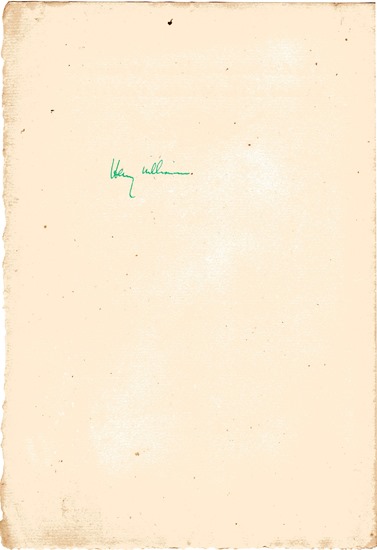

HW’s signature appears, in red or green ink, on the title page verso, an otherwise blank page:

At the back of the book (p. 24) it states:

This first edition of The Ackymals

is limited to 225 copies, each signed

by the author. Printed by James

and Cecil Johnson at the Windsor

Press, with decorations by Julian

Links.

Underneath which appears the Windsor Press oval ‘cartouche’ or colophon – then:

Copy No. --- (the number being added by HW in red or green ink)

The illustrator was hardly taxed: there is only one, of a charming cottage with thatched roof, on the first page of the story:

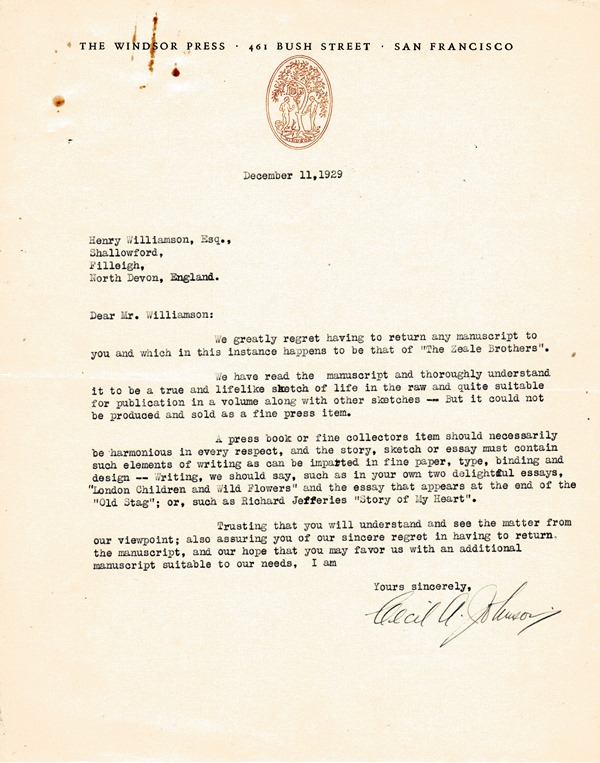

HW evidently then submitted a further short story, for in December 1929 a further letter from Cecil Johnson regretfully turns down 'The Zeale Brothers':

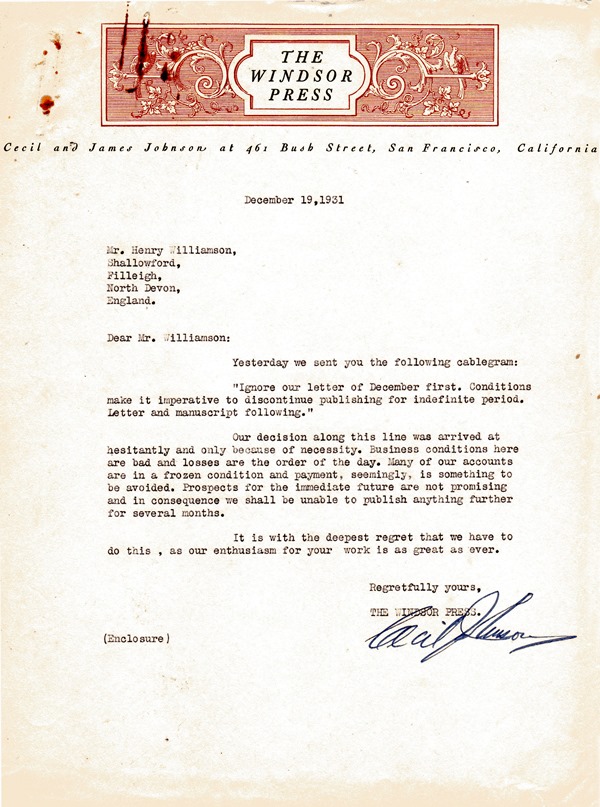

Two years later, with America in the middle of the Great Depression, The Windsor Press was in financial crisis, for on 19 December 1931 Johnson wrote:

It sounds, from this, as though another project was under way, but there is no record of what this may have been in HW's papers.

*************************

'The Ackymals' (The London Mercury, January 1927):

As cut by HW from the magazine:

*************************

There are no critical reviews for The Ackymals available: as a private and limited edition this is understandable. The story was to be incorporated into The Village Book, which was published in 1930 (as was 'The Zeale Brothers', mentioned above).

*************************

The cover is attractive, although not particularly appropriate to the content:

*************************