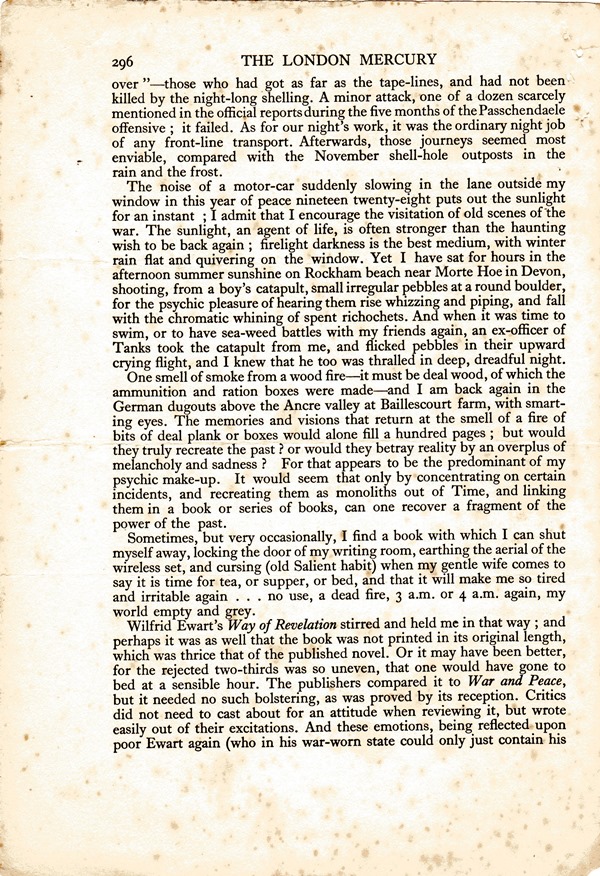

‘REALITY IN WAR LITERATURE’

|

|

|

The London Mercury, January 1929 |

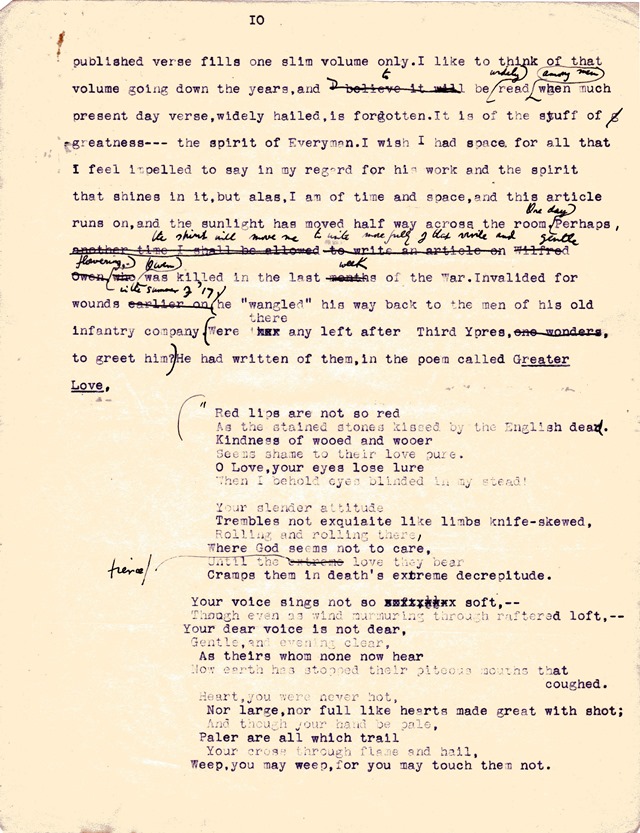

Typescript, 'War Books and Memories'

1929 version (in The London Mercury)

Henry Williamson's revisions in The London Mercury

This important essay, of considerable length – 38 printed pages – is to be found in its third and final version in ‘Essays on Books and Authors’, being Part Two of The Linhay on the Downs and Other Adventures in the Old and New World (Cape, 1934, pp 224–62). The essay has 6 sections and 4 Postscripts.

‘Reality in War Literature’ is basically a survey of about fifty books written by men who had actually taken part in the Great War, as it was known until the start of the Second World War. HW admits in his essay:

This record of entirely personal impressions of War books includes only what I like.

It is, therefore, a fairly idiosyncratic list – but a most interesting record, and contains most of the books that have stood the test of time and are now considered to be among the best of their kind. However, the essay is somewhat unbalanced in its structure, and a disproportionate amount of space is given to Edmund Blunden’s Undertones of War (although HW explains why in his ‘Postscript IV’). ‘Postscript I’ gives the gist of a letter from Edmund Blunden about his book (a riposte to HW’s comments, which adds to the Blunden overload); while ‘Postscripts II and III’ list more recently published books, though with little content, critical or otherwise, other than their titles.

The Postscripts are there because the basic essay had already been printed five years earlier in the prestigious literary magazine The London Mercury in January 1929, and the reason for the long Blunden entry was that in the previous month (i.e. December 1928) its editor, Jack Squire, had sent HW a telegram asking him if he would review the book ‘to oblidge me’ – as HW prints in ‘Postscript IV’ of the Linhay on the Downs version:

|

SRP 11-13 a.m. London City W. Croyde, 6 De 28 Reply paid Williamson Skirr Cottage

Could you do four thousand words by the fifteenth on Blundens Book to oblidge [sic] me

SQUIRE |

(It is this London Mercury version of the essay, which Blunden had read before publication, that prompted his letter of riposte to HW.) Jack Squire, eminent critic (later Sir John Squire), had been instrumental in putting forward HW’s great book Tarka the Otter for the Hawthornden Prize for 1928. HW obviously did not hesitate to ‘oblidge’! But in so doing, he incorporated an even earlier essay written two years previously.

*************************

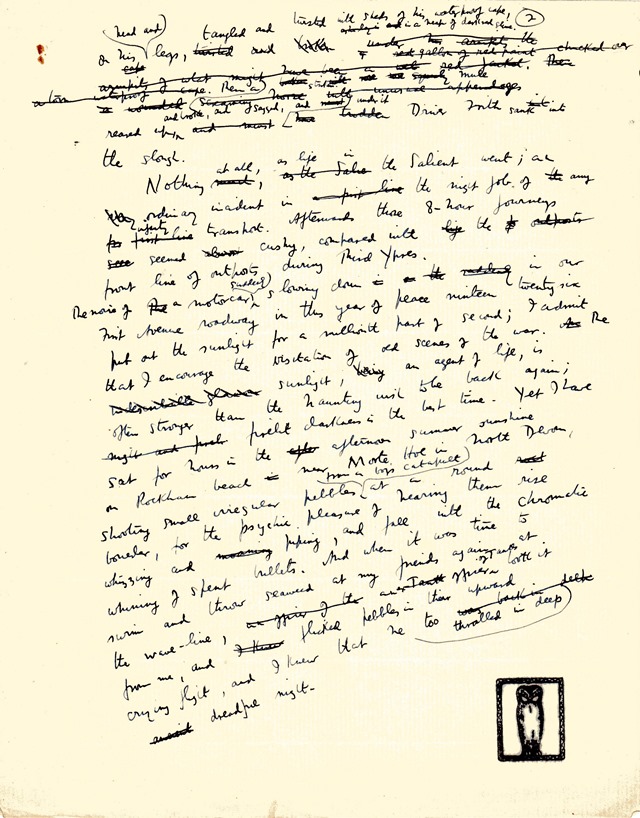

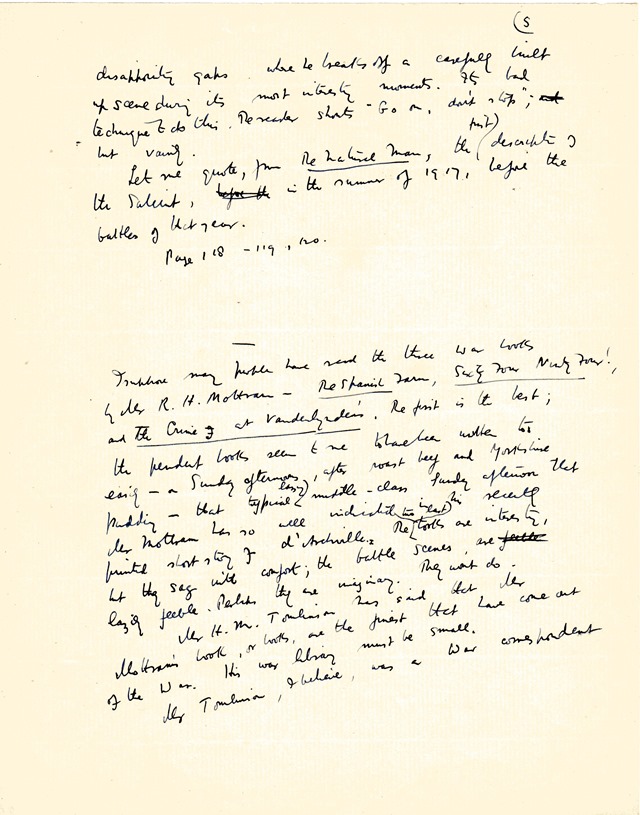

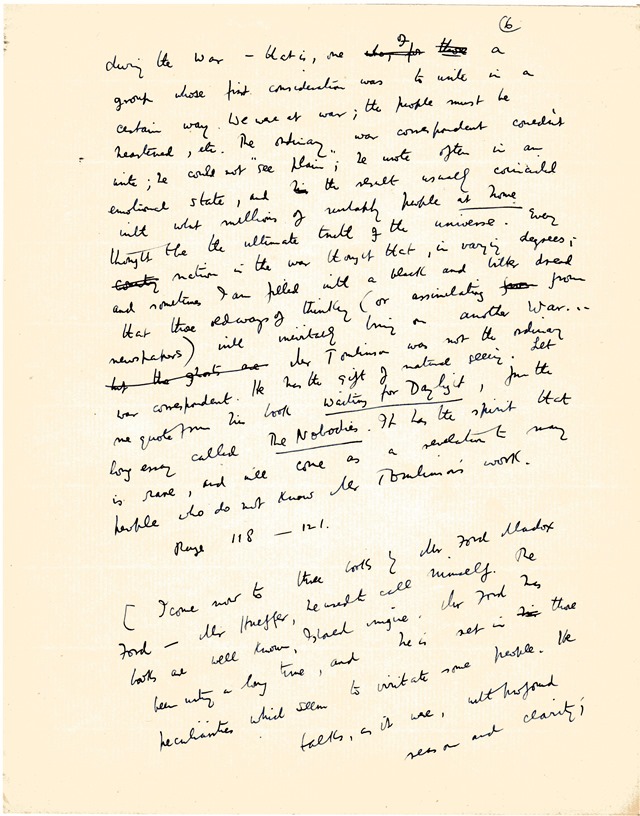

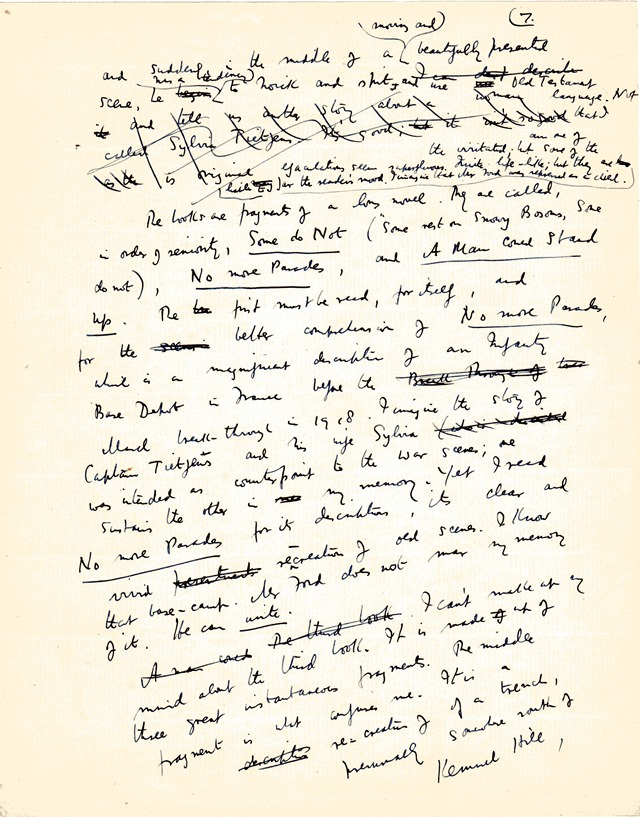

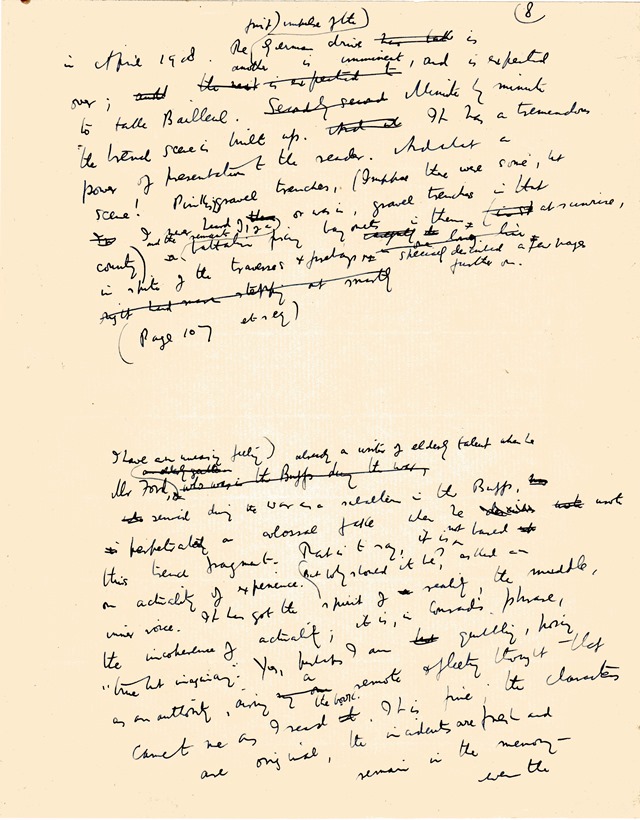

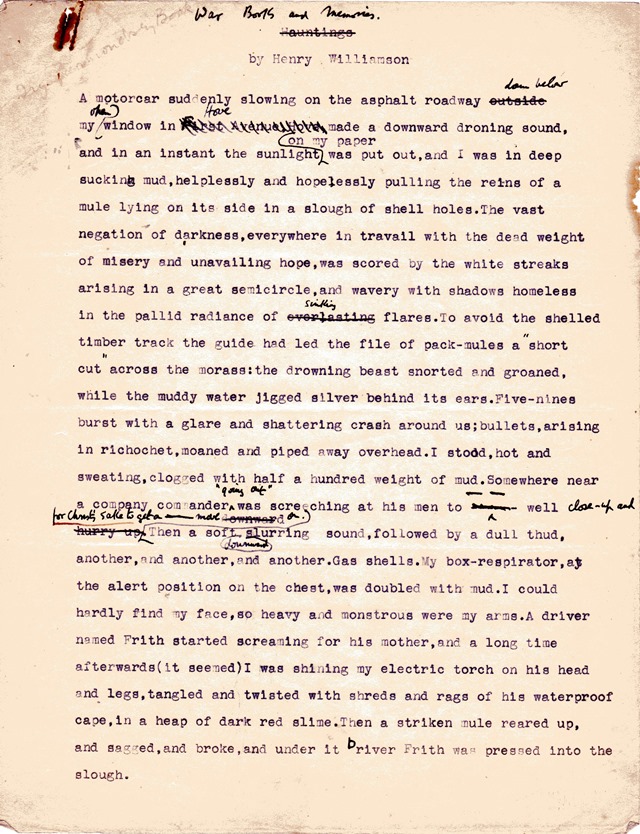

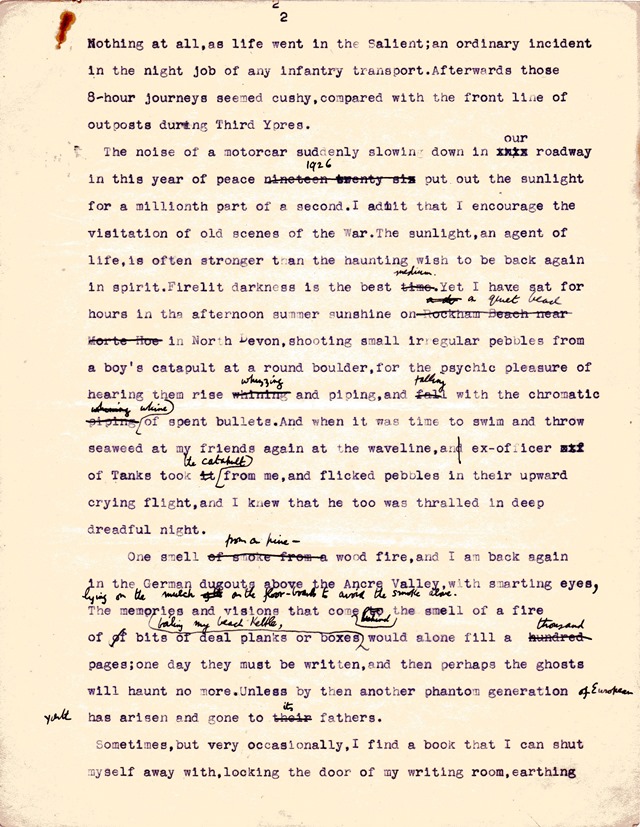

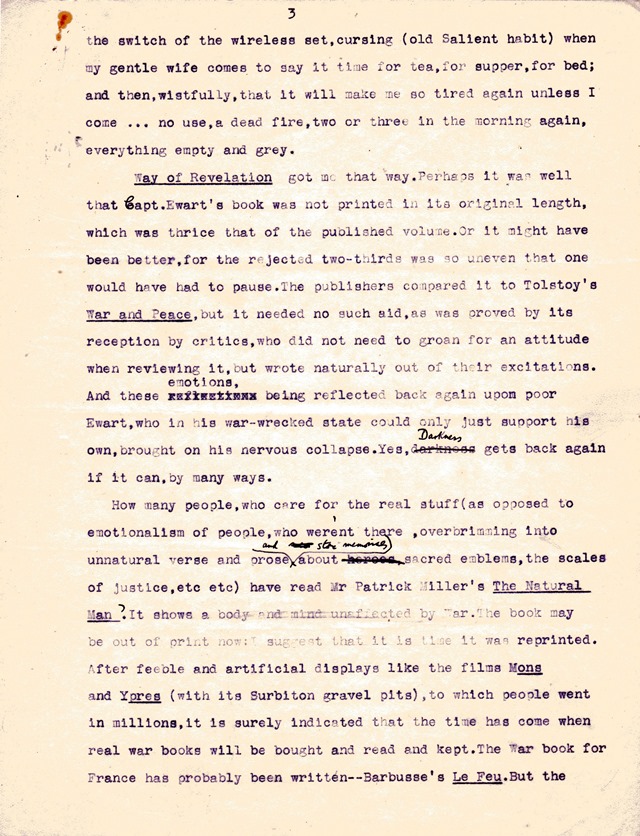

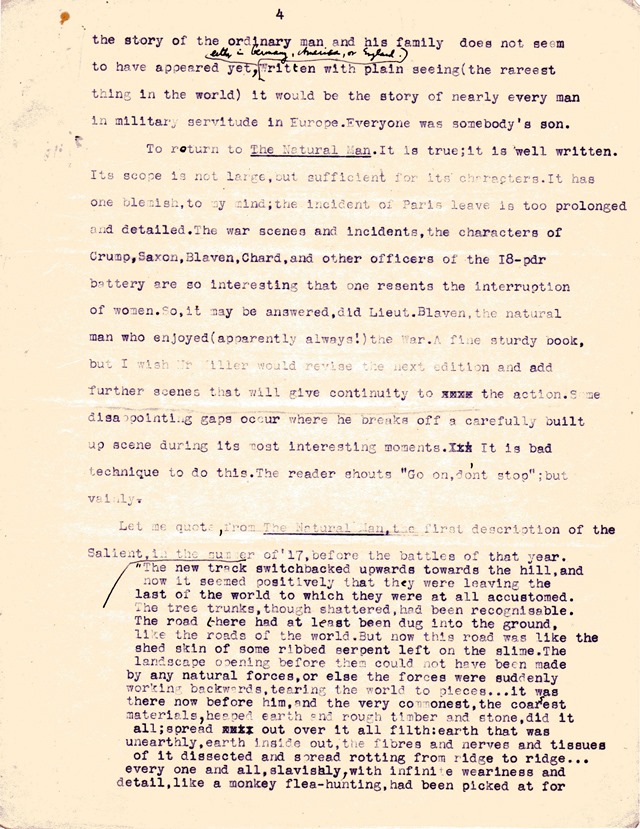

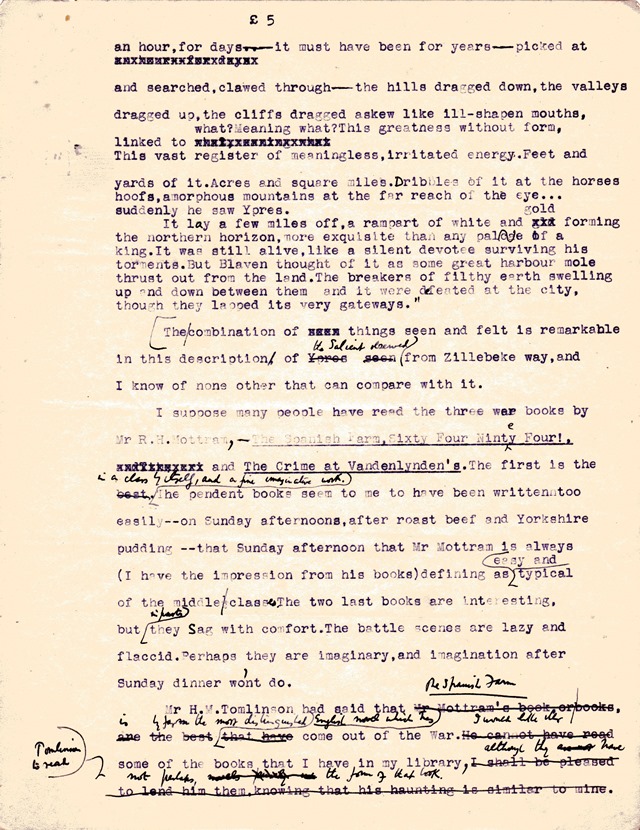

The original untitled manuscript in HW’s archive covers 11 quarto pages of rather scrawling writing, and is dated 12 December 1926. Helpfully, it has an attendant typescript, though some revision has taken place, and the typescript itself is revised. This typescript was given the title of ‘Hauntings’, but that is crossed out and a rather staid and stilted ‘War Books and Memories’ inserted instead. (See the scans below of the 1926 MS and TS.) It is not until the London Mercury version of the essay that the title ‘Reality in War Literature’ appears.

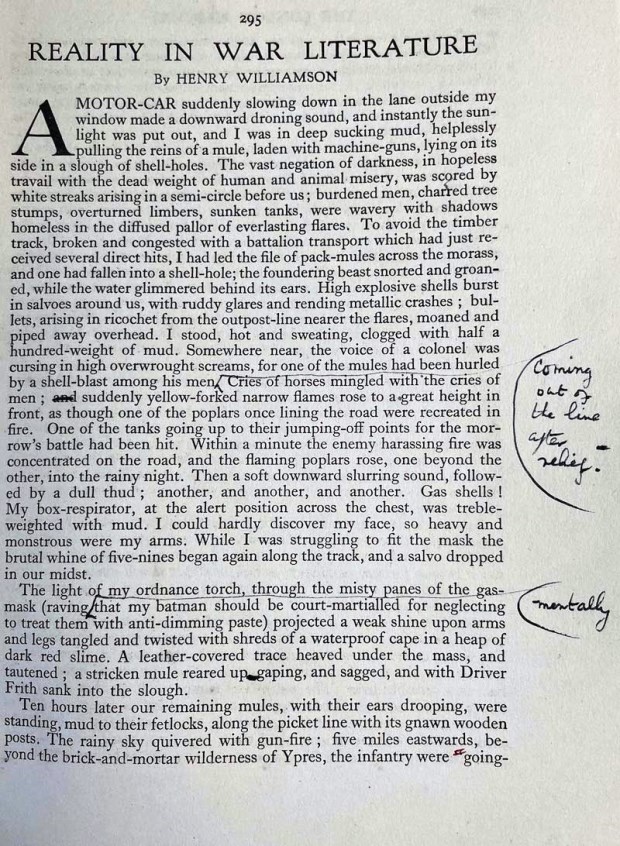

This first version – and indeed all three versions (with slight variations) – opens with a searing description, generated by:

A motorcar suddenly slowing down in the asphalt roadway down below my open window in Hove made a downward droning sound, and instantly the sunlight on my paper was put out, and I was in deep sucking mud. . . .

HW has been catapulted back into the Great War. And we read here of, first, ‘straight-forward’ shelling creating lurid chaos, and then a gas-shell attack experienced by the writer while taking supplies up the line at night to the Front. This nightly exercise was undertaken by a team of drivers and mules pulling heavy loaded limbers. It was an extremely difficult and dangerous undertaking, making their way in darkness along the makeshift board walks, or ‘duckboards’, while crossing a treacherous, muddy, water-filled crater landscape constantly shelled by the enemy. To avoid the shelling on this particular night a guide takes them ‘on a "short-cut" across the morass'. Either they are seen or it is a random shell that explodes among the convoy of limbers, followed by two or three gas shells which spread their deadly contents.

A driver named Frith started screaming for his mother . . . his head and legs tangled and twisted with shreds and rags of his waterproof cape, in a heap of dark red slime. Then a stricken mule reared up, and sagged, and broke, and under it Driver Frith was pressed into the slough.

This vivid recreation of the scene gets slightly modified in the London Mercury version, with further small revisions for Linhay on the Downs – whichever version is read, it is still utterly horrifying. It is certainly the ‘Reality of War’.

No date is given in the essay, but this devastating event actually took place on the night of 7/8 June 1917, and describes an actual experience. Although this was not known at the time of these essays (and indeed very few facts about HW’s war service were known prior to his death in 1977), HW was then Transport Officer for 208 Machine Gun Company and his tasks included this nightly run, taking replacement machine guns, ammunition and supplies to the men of the Company in the Front Line. That night, Driver Frith was killed when a shell exploded nearby, severely wounding both man and mule, which slipped down into the mire and they both sank down into and under the mud. His body was never recovered. Only feet away from him, HW narrowly escaped death himself (one presumes the shock wave of the shell passed over his head), but was badly gassed. It is a harrowing scene – and in all the thousands – millions – of words HW wrote, this is the only place that it is ever mentioned. His diary for 8 June merely reads: ‘Went sick this morning.’ And the following day: ‘Admitted to Field Ambulance Hospital . . . Spewing all night & day.’

Little was known about Driver Frith – Private Willis Hirwin Frith – other than that he had indeed been a mule driver in HW’s unit, until John Gregory, deeply touched by this story, researched his background (see the web page Driver Frith.) Born in May 1897, Frith was just 20 years old when he was killed (HW, his officer, was only a year older). HW was hospitalised the next day and in due course was sent back to England where, when he was fit enough, he undertook a long convalescence; still without a full bill of health, he was sent to Felixstowe towards the end of the year to join the Third (Special Reserve) Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment.

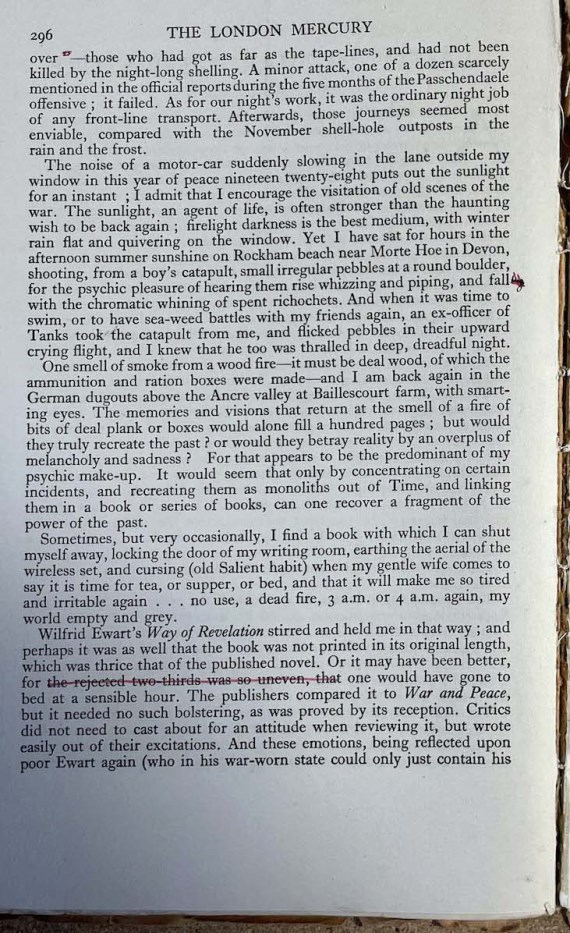

In this essay HW now gradually moves towards his actual subject. Telling us his memories of the war would fill many pages:

But would they truly recreate the past?

It would seem that only by concentrating on certain incidents and recreating them as monoliths out of Time, and linking them in a book, or series of books, can one recover a fragment of the power of the past.

Then we arrive at the central matter: ‘very occasionally, I find a book . . .’

The early first version covers only seven authors with attendant books: first on the list (and indeed first on the list of all three versions) is Way of Revelation by Wilfred Ewart; then Patrick Miller's The Natural Man; third is Ralph Mottram, with three books mentioned – The Spanish Farm, Sixty-Four Ninety-Four, and The Crime at Vanderlynden’s, collectively known as The Spanish Farm trilogy; H. M. Tomlinson’s long essay ‘The Nobodies’ from his Waiting for Daylight; Ford Maddox Ford’s (as HW pointedly notes ‘Mr Hueffer, he used to call himself’) Some Do Not, No More Parades, A Man Could Stand Up, today known as the Parades End trilogy; then a brief mention of Rupert Brooke’s war poems, which leads into the poems of Wilfred Owen.

This original version has a long passage about Owen’s poetry. Even so, ‘I wish I had space for all that I feel impelled to say in my regard for his work and the spirit that shines in it, but . . .’ He then quotes the poem ‘Greater Love’ in full. This is changed in the London Mercury version, where he quotes ‘Exposure’. (He also mentions this poem in his Sunday Referee article ‘Wood Fires’, 19 November 1933.) But rather strangely, the final Linhay on the Downs version has only a brief mention and a two-line quote from ‘Apologia pro poemate mea’ (see later).

The original typescript of the essay ends with a return to the opening remark:

I have written . . . moved by the sound, as of a phosgene gas shell, made by a motorcar in the road below.

************************

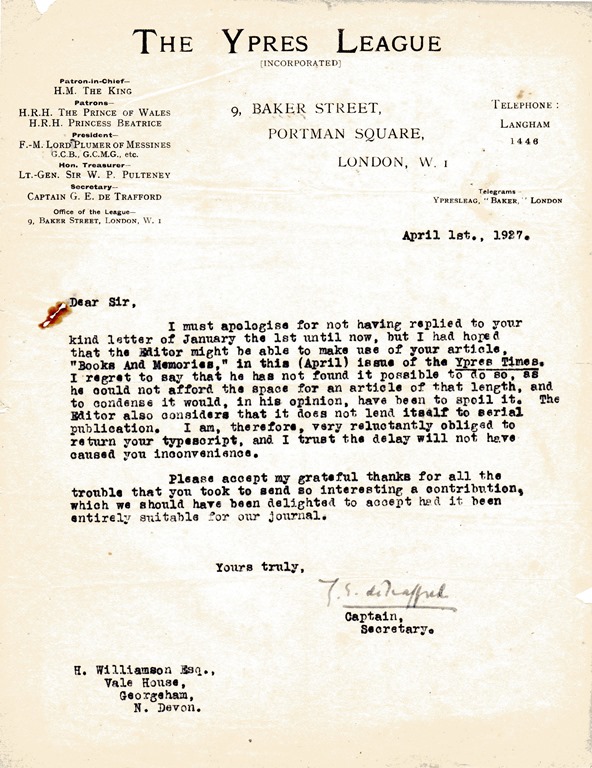

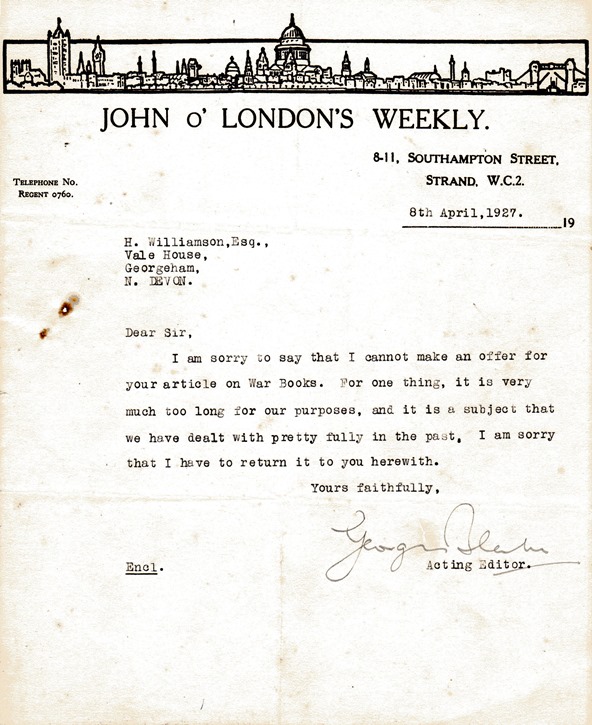

HW tried to get the original version of this essay accepted by various magazine, notably The Ypres Times:

and John o’ London’s Weekly:

Thus rejected, it then lay fallow until resuscitated to open the London Mercury version – which is ostensibly the review of Edmund Blunden’s Undertones of War as requested by Jack Squire.

What caused the genesis of this essay, written, as is evident from the handwriting, with sudden urgency and emotion in early December 1926? There is really nothing within HW’s archive to explain the answer but, by putting various points together, it is possible to come to a reasonable conclusion.

We know that while he was still in the army HW had determined to become a writer. Indeed, the first evidence of this appears while he was on that convalescent leave recovering from the gas attack that killed Driver Frith, when he was recommended to write as therapy for his psychological trauma (a trauma that never left him). He wanted to write the ‘Truth’ about life and the war in particular, but his early published writing shies away from any actual description of that war. It was still too near and too painful – and no doubt he felt or knew that he was not yet capable of doing justice to the standard he was setting himself. However, as I have pointed out in many examinations of various aspects of HW’s writing, all that early writing (amend that to all – or certainly most – of his writing) can be seen as an allegory of the war: the violent death of innocent victims at the hand of an aggressor.

There are various events leading up to the writing of this essay that undoubtably brought things to a head and lanced the boil. Firstly, in May 1925 HW was married and, obviously with the comfort of a wife as companion giving him courage, the couple spent their honeymoon on a tour of the battlefields of the Western Front. The fact that HW kept a detailed daily record in a black notebook of where they went and what he saw perhaps reveals that he was already planning, or certainly gathering material, for future writing. The notes are detailed, and this visit would have brought back to the surface of his mind many things that had lain hidden for few years – perhaps not least that night of the gas attack in 1917. But importantly, HW can now look openly at the events of the war and its effects.

Perhaps more crucially here is the fact that on 4 November 1926 HW attended a dinner at the Connaught Rooms in Great Queen Street, London for a reunion of survivors of the London Rifle Brigade who had travelled out to France on 4 November 1914 in the troopship Chyebassa, recording in his diary:

Attended reunion of the original L.R.B. survivors!

Menu cards from the event still exist in the archive, which have been signed by the men he knew and fought beside during the first few months of the war and including the experience of the Christmas Truce in ‘Plugstreet’ Wood, together with a sketch of the layout of trenches drawn by one of them. HW recorded these facts and notes in the same black notebook, and immediately following those he had made on his honeymoon trip to the battlefields.

One of the men present at that reunion was Douglas Bell, who had been at the same school as HW – Colfe’s – though he was a little older and their years did not overlap. Bell was writing a book about his own war experiences. HW was by then a reasonably well-known writer with six books published, while the seventh, Tarka the Otter, was in the finishing stages. Bell asked for his help, which HW willingly gave, writing an Introduction for the book, which was published anonymously as A Soldier’s Diary of the Great War (Faber & Gwyer, 1929).

That reunion – and the work on Bell’s book – following on from his visit to the battlefields the previous year would have really stirred and sharpened HW’s thoughts about the war, and the books then being written and published about it. He also learnt that there was an official visit to the battlefields planned for the following year, to commemorate a Memorial to the London Rifle Brigade together with the formal opening ceremony for the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres. He did not wish to be involved in any official gathering, but decided to make his own way there; which he did, in company with his brother-in-law, ex-tank officer Bill Busby, in early June 1927; thereby – in that little black notebook – gathering the remainder of the material that became The Wet Flanders Plain, published two years later.

It is obvious to me that the meeting with his war-time comrades at the Chyebassa dinner brought all his thoughts about the war to the forefront of his mind, for only a month later we find him pouring out his thoughts in this essay.

Readers may be puzzled by the reference to ‘Hove’ in HW’s original opening sentence; indeed the MS actually states ‘First Avenue, Hove’. It is omitted from later versions. The answer is a straightforward one: at the time of writing HW was staying at the home of his great friend, the prolific writer Petre Mais.

While on this visit, HW had a few days previously made his way to the nearby home of John Galsworthy. He poured out his doubts about himself and his writing, while the established Galsworthy was no doubt encouraging and helpful. Although there is no evidence, it is entirely possible that the two men also spoke of the Great War and the current outpouring of literature about it. That evening Galsworthy wrote to Edward Garnett, drawing the attention of HW’s writing to this eminent critic (and that in turn was to lead to Garnett in due course sending a copy of Tarka the Otter to T. E. Lawrence).

It is clear that, at the point of writing, the subject was at the forefront of HW’s mind; and it may well have been that a car suddenly braking, perhaps skidding slightly, outside his window, threw him back into that most fearsome night, the night when he saw the most gruesome death of his mule driver, the night when he could so easily have been killed himself. Throughout HW’s life it took very little to throw him back into the war. The writing here is heart-felt – very immediate and raw. The boil had burst. It was no doubt a catharsis. When he next wrote about the war, the raw emotion evident here is no longer obvious.

There are one or two points to particularly note within the writing itself. As stated, HW had just finished, or was in the final stages of writing, what was to become his most famous book, Tarka the Otter. I find it quite startlingly noticeable that his original description of Driver Frith’s death is described in words that can be paralleled with the death of Tarka:

Tarka the Otter (last paragraph):

They saw the broken head look up . . . and then the hound was sinking with the otter into the deep water . . . and as they watched another bubble shook to the surface, and broke . . .

'Reality in War Literature', typescript:

Then a stricken mule reared up, and sagged, and broke, and under it Driver Frith was pressed into the slough.

In a later versions HW changed the word ‘pressed’ back to ‘sank’, as in the original manuscript (so matching ‘sinking’ in Tarka), making the connection even closer. This was surely deliberate.

Another very noticeable connection is the similarity of thought in the opening here to that expressed in the opening of another essay written shortly after this: ‘I Believe in the Men Who Died’, printed in the Daily Express, 17 September 1928. In the ‘Reality in War Literature’ essay it is the sound of a car suddenly braking that jerks HW back into the war. In the ‘I Believe . . .’ essay it is the sound of the bells of Georgeham church: HW ascends the tower with the bellringers and:

The great sound sweeps other thought away into the air and the earth fades; the powerful wraith of those four years of the war enter into me, and the torrent becomes the light and clamour of massed guns that thrall the senses.

That essay became ‘Apologia pro vita mea’, being the Foreword to the book that relates his return visits to the Battlefields: The Wet Flanders Plain. The title ‘Apologia pro vita mea’ is very obviously a reference – a homage – to the poem by Wilfred Owen, ‘Apologia pro poemate mea’, quoted in the Linhay on the Downs version of the essay.

One has to presume that HW felt ‘Reality in War Literature’ deserved (as it certainly did) a wider and more permanent placing than its appearance in a magazine, however prestigious that magazine may have been at the time, and decided to include it in The Linhay on the Downs. This decision allowed him to update the list of books to be included – but also to expand his original text. For instance, in the London Mercury version we find the following sentence, of great importance to the understanding of HW’s psyche and thus his writing.

For myself, I have possibly never recovered from certain shocks and terrors experienced in 1914: so that an impaired mentality is . . . [passing judgement on the writing of someone who did not suffer greatly]

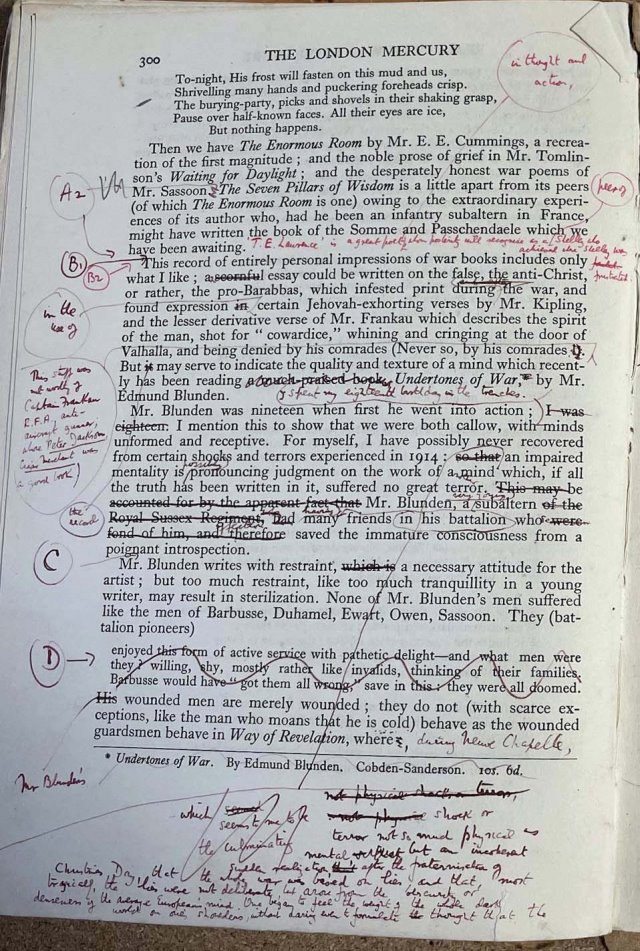

The next paragraph reads ‘Mr Blunden writes with restraint . . .’

In the Linhay on the Downs version, however, there are over two pages of writing between those two paragraphs: two pages of HW’s reasoning and thoughts on the causes of the war, including the iniquity of the Versailles Treaty.

HW is quite critical of various aspects within Blunden’s book, which occasioned the letter of riposte, where Blunden explains that he wrote the book from memory, not having any of his notes in Tokyo, where he was then teaching. One does feel that in this case perhaps he should have waited until he either returned or had access to those papers! A point that I suspect HW is actually subtly stating (with tongue in cheek) by including a précis of Blunden’s letter as a postscript.

Wilfred Owen’s poetry is given prominence as the greatest poet of the Great War: ‘whom men of future will hail as the poet of the lost generation.’

But there is a central point to HW’s essay which is easily missed, a pivot on which he actually hinges the whole critique: the standard against which all war books should be judged, the book considered by many to be the greatest war book of all time – Lev Tolstoy’s War and Peace (Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoi, 1828–1910), a story of five families in Russia at the time of the Napoleonic wars. Written between1865–69, it was published in four volumes with various Epilogues.

The point gets introduced as Putnam, the publisher of Wilfrid Ewart’s The Way of Revelation in 1921, had rather absurdly puffed up the book by stating it made comparison with War and Peace. HW very firmly states that the book to meet the necessary criteria for this comparison has yet to be written:

Lonely towers the mighty Everest in some young writer’s imagination.

The only book that comes anywhere near meeting the criteria, as far as HW was concerned, was Henri Barbusse’s Le Feu (translated as Under Fire), although he also rates George Duhamel’s Civilisations very highly:

Both books have the divine power of fusing both spirit and letter of reality and casting the amalgam of truth into words. [But] Although Barbusse sees philosophically beyond the immediate situation Le Feu does not encompass the depth envisaged in the Russian book.

The London Mercury version notes:

Those of us interested in the world of books begin to talk of the appearance of the great war book that shall stand somewhere near War and Peace. Barbusse’s Le Feu? Still we await the war book.

In the final Linhay on the Downs version, ‘the mighty Everest’ sentence continues:

It will need titanic vitality to recreate the lost world of 1914–18 of which every poor human mole that toiled and suffered and survived those years shall say: This is my molehill, yet it is a mountain and nearest the stars of Truth.

And further:

Until the war novel that recreates the war appears, if it is to appear, . . . the spirit of Truth . . . informing the mind . . . is needed among all men . . . if their children are to remain their children in the universal sunshine.

(This is in 1935: HW is warning against another war if the lessons from the Great War have not been learnt.)

Those rather vague statements are as near to analysis of the necessary criteria that we are given. But HW is of course laying claim, if only to himself, that it will be his book that in due course will stand comparison with the great Russian novel War and Peace: his book that will embody the ‘reality of war literature’.

*************************

A detailed background commentary on the books and authors considered in ‘Reality in War Literature’ can be found in Anne Williamson, ‘Witness to War’, HWSJ 50, September 2014, pp 4-26.

*************************

Interestingly, among his various 'Reality in War Literature' papers HW kept a cutting from the BBC's The Listener of the transcript of the talk 'The Somme Still Flows' by Edmund Blunden, which was broadcast on 1 July 1929. Reproduced here are the magazine's cover and the opening paragraph of Blunden's talk. HW's note on the front cover reads: 'To condense the Somme for P. into one chapter' ('P.' being Phillip Maddison, the protagonist of the book) – he was to use some of this material in The Golden Virgin. The full text of this piece has been reprinted in Edmund Blunden: Fall in, Ghosts: Selected War Prose (Carcanet, 2014, edited by Robyn Marsack).

*************************

1926 version: the original, untitled essay:

*************************

Typescript: 'War Books and Memories'

*************************

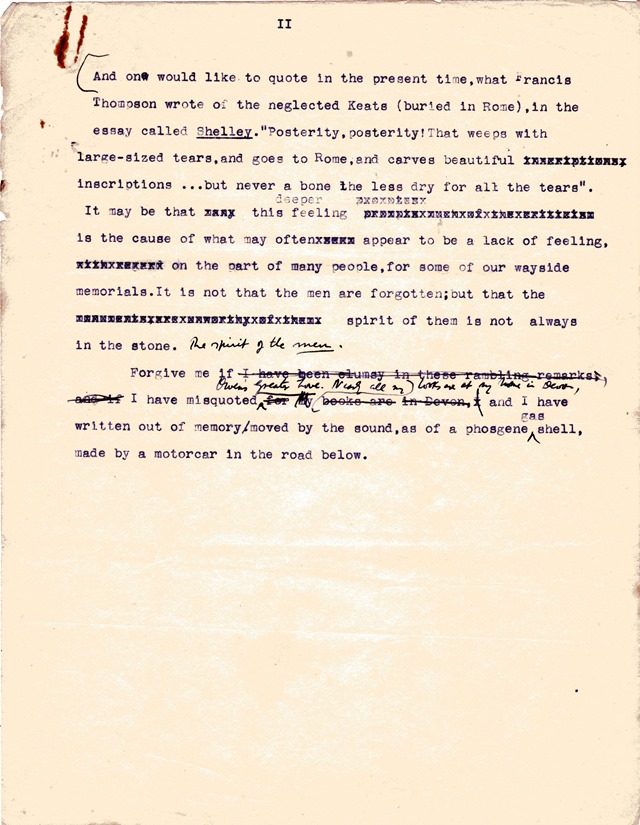

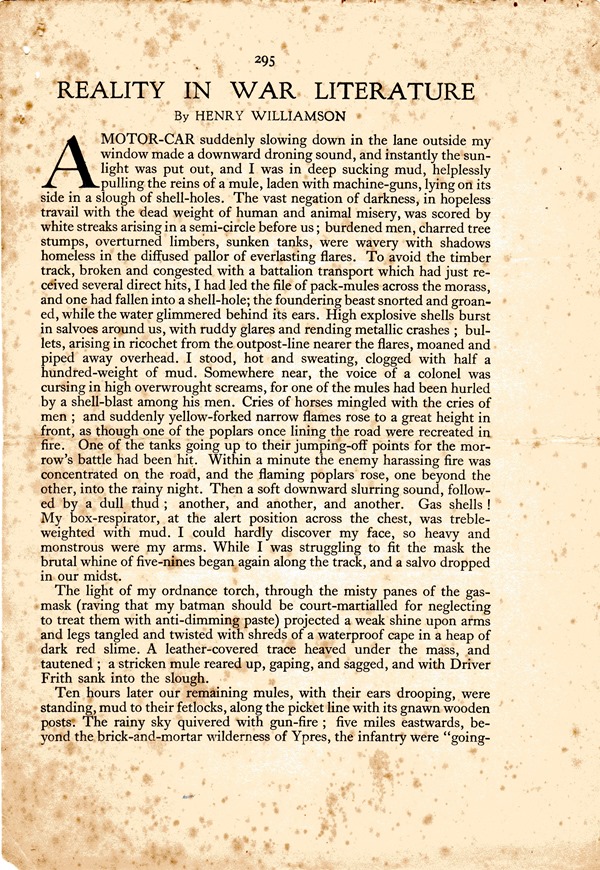

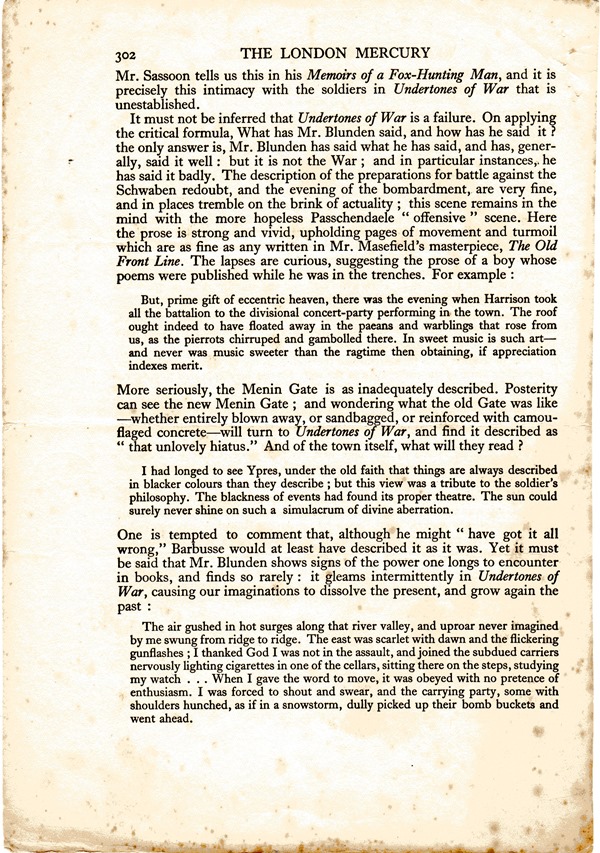

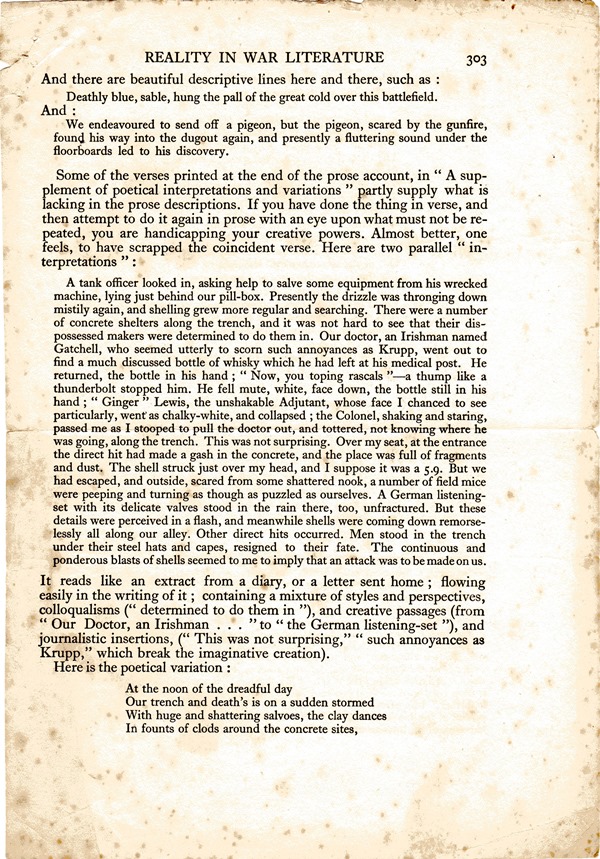

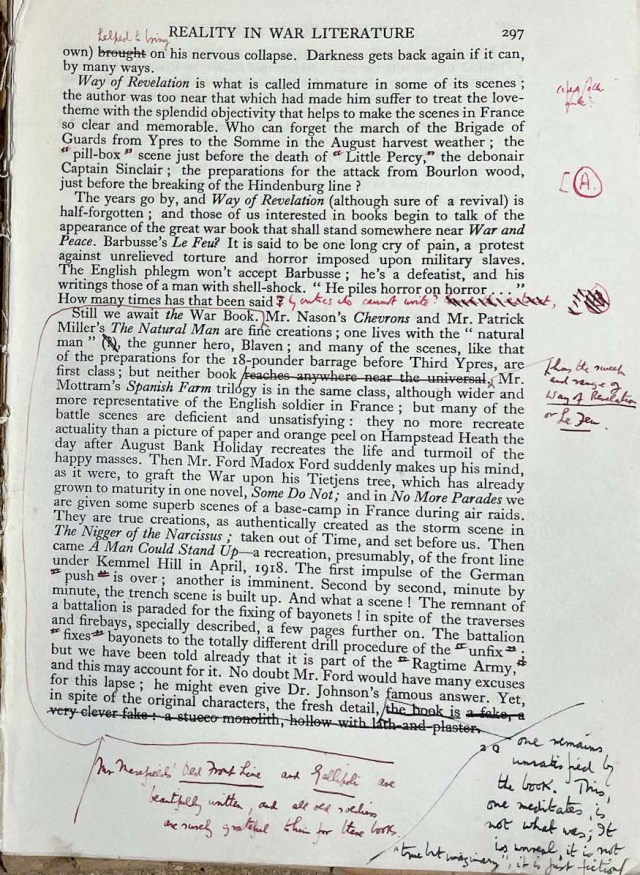

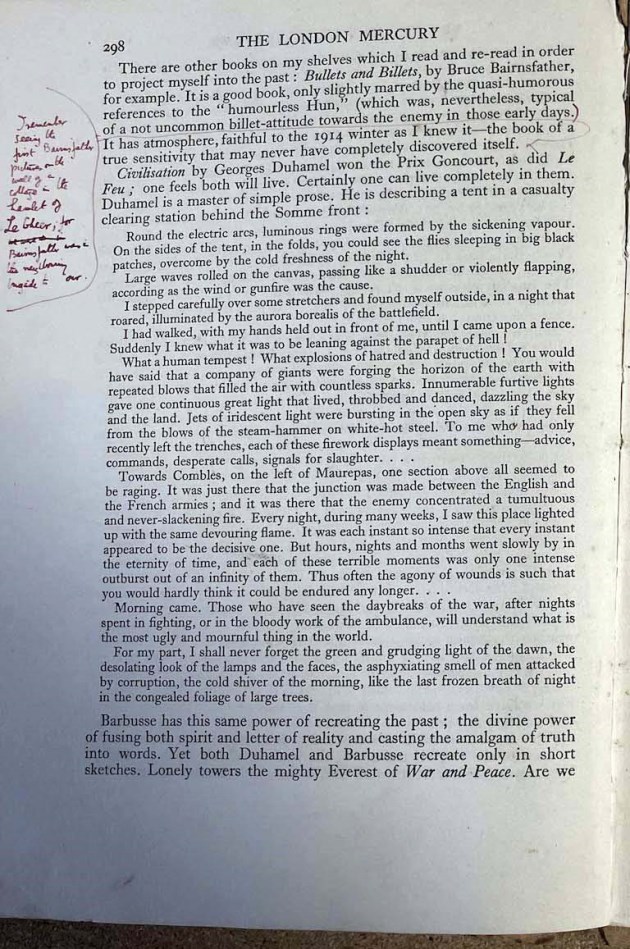

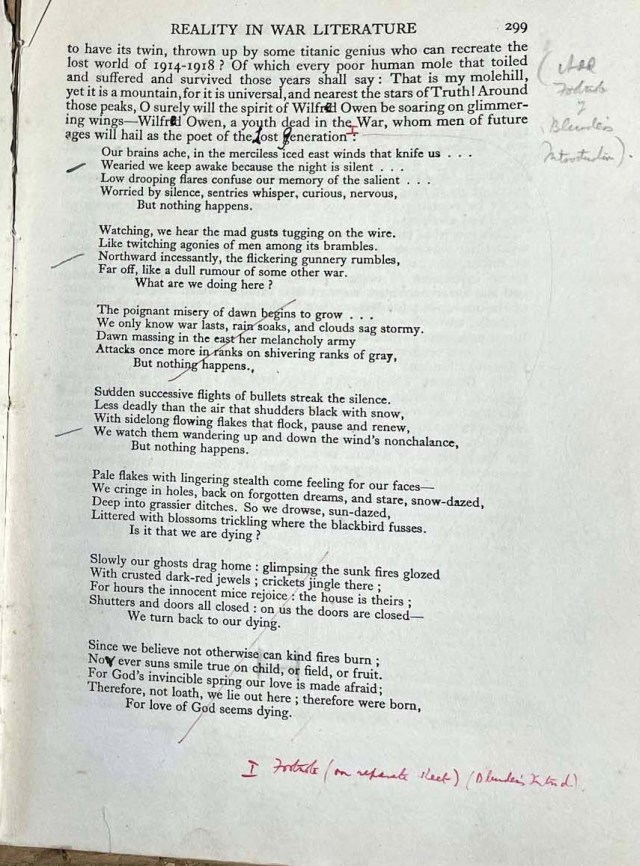

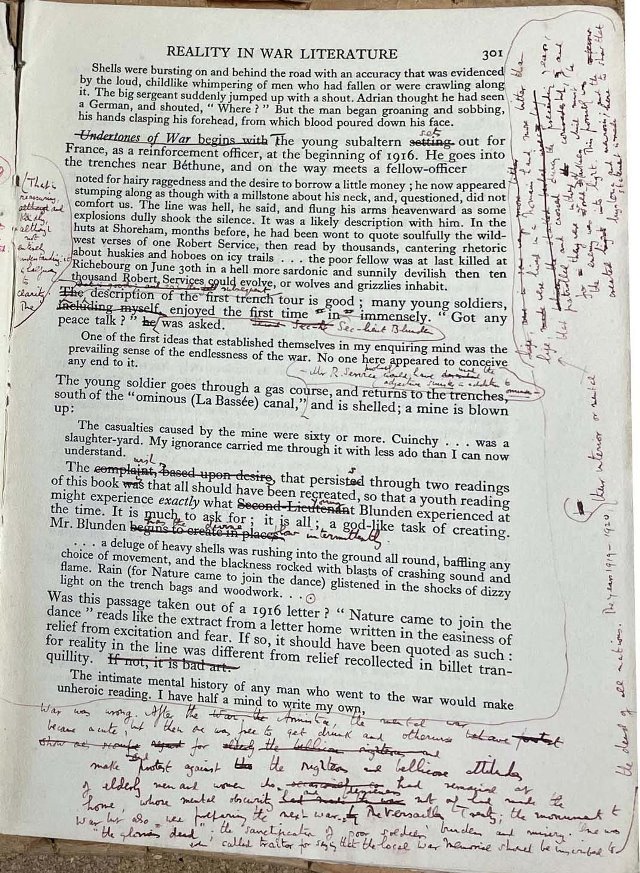

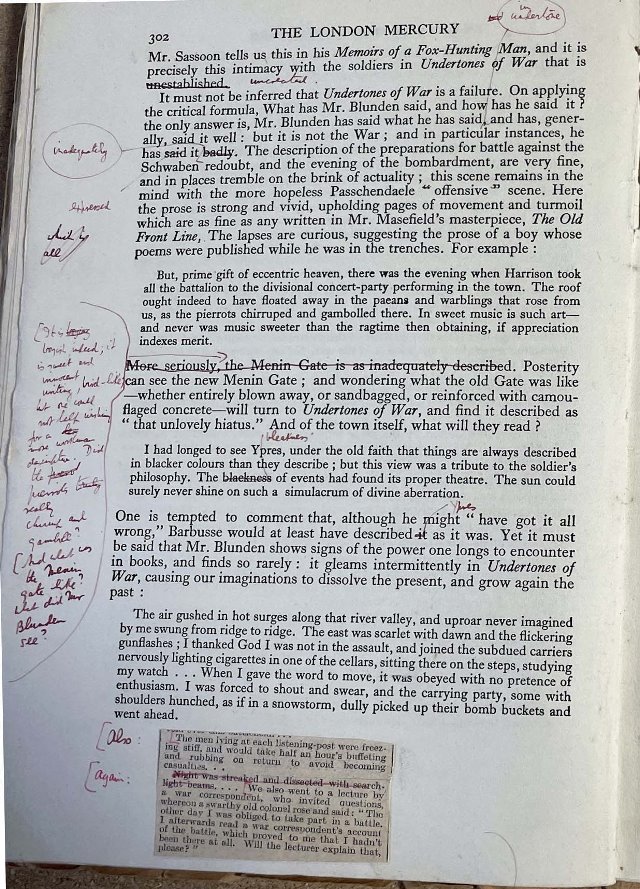

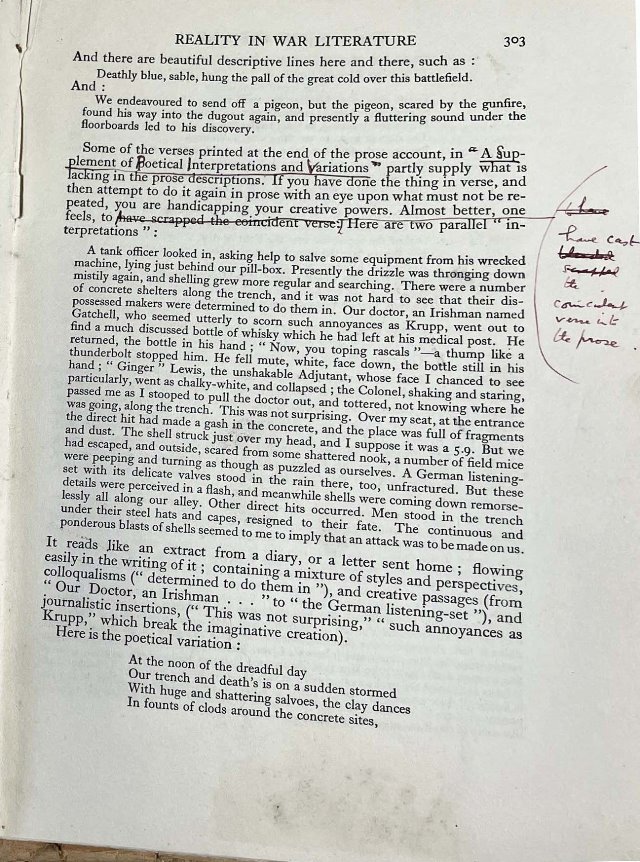

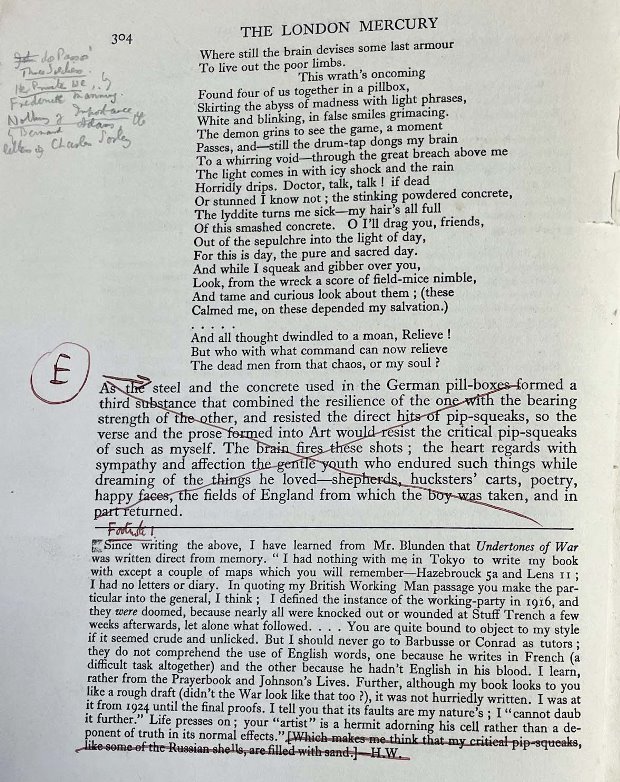

Version 2: The London Mercury, January 1929, Volume XIX, No. 111 (these pages were cut out of the magazine and kept by HW)

*************************

Henry Williamson's revisions in The London Mercury:

In October 2022 a copy of this issue of The London Mercury came to light that contained manuscript revisions by HW to the essay. These proved to be a preliminary revision for the third version of the essay that appeared in The Linhay on the Downs (there are still a few differences to the printed version). The images of the essay with HW's notations are reproduced below with the kind permission of Dr Paul Kelly:

*************************

The London Mercury, January 1929. Vol. XIX, No, 111. The label on the front, advertising the major contents, was a standard practice with the magazine. These labels, lightly stuck at the left edge, were usually removed by recipients or were lost over the years, and are now uncommon.

*************************