NO MAN'S LAND

With the war poems of Siegfried Sassoon

|

Appendix: HW and Siegfried Sassoon

Written and narrated by Patrick Garland

Produced by Tristram Powell

Shown at 9.55 p.m. on BBC1, Armistice Sunday, 10 November 1968

Length: 40 minutes

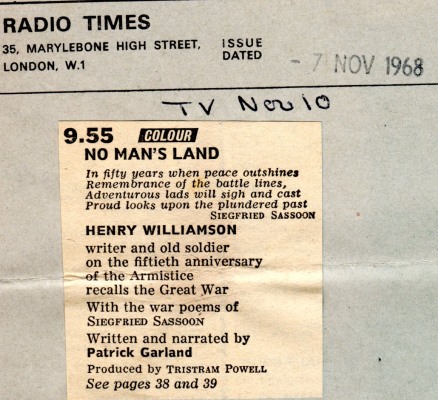

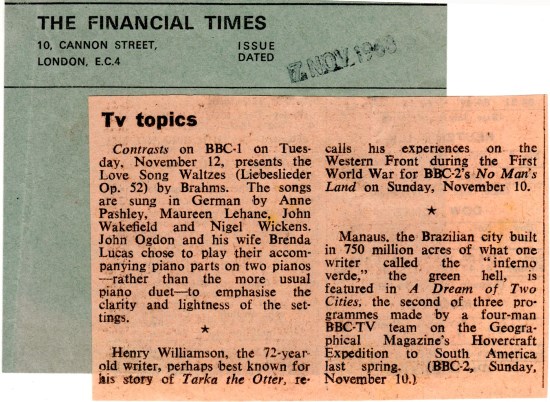

11 November 1968 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the ending of the First World War. The Radio Times, in its 7 November issue, listed No Man's Land among its programmes for the evening of Sunday, 10 November, on BBC2:

More legibly, enlarged from the press cutting held in the Archive:

The Radio Times also made a feature of the programme on its central pages:

*************************

Unfortunately there is very little background information in the Archive about the making of the film.

HW spent the weekend of 1–2 June 1968 at Spode House, a Conference Centre under the auspices of the Aylesford Priory / Aylesford Review / Fr Brocard Sewell, where he met Penelope Shuttle and was briefly very attracted. (He does admit in one of his diary entries that he is desperate for 'love' – by which he probably means more 'attention' – and that almost any attractive young girl who showed interest in him would likely meet his requirements.) On his return, with no previous preamble, his diary states:

4 June 1968: See Pat Garland & T. Powell at Ilfracombe.

They came yesterday. Pleasant two, including Miss P.

I put up Patrick for night, the others to Lee Bay Hotel. Upshot of discussion I write to Dawyck Haig, may we film at Bemersyde in July.

Dawyck Haig (Earl Haig) was the son of Field Marshal Earl Haig; Bemersyde was the Haig family home on the Tweed in Scotland. HW and the current Earl were friends.

11 June: [re above] Write to Tristram Powell re BBC TV film in July NOT August.

HW noted in his diary at beginning August:

Monday, 5 August: Tristram Powell & BBC TV camera crew to arrive.

6 August: Dawyck Haig leaves Pickwell Manor.

(The Haig family had a holiday cottage at Pickwell at the bottom of the cliff below HW's Field. This entry may or may not be connected to the filming; but in any case there was no subsequent involvement.)

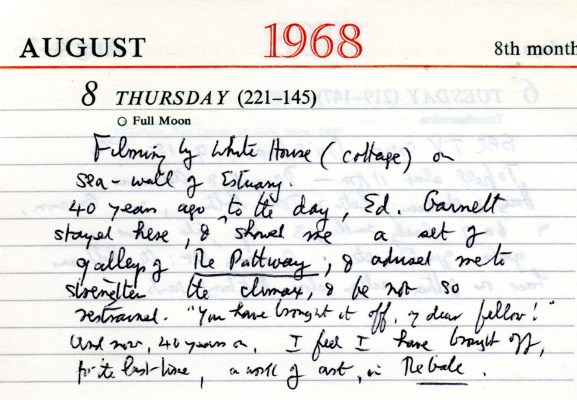

HW's diary entry for 8 August reads:

9 August: ? Last day of shooting (BBC TV)

On 19 August HW was supposed to meet Patrick Garland in London but cancelled.

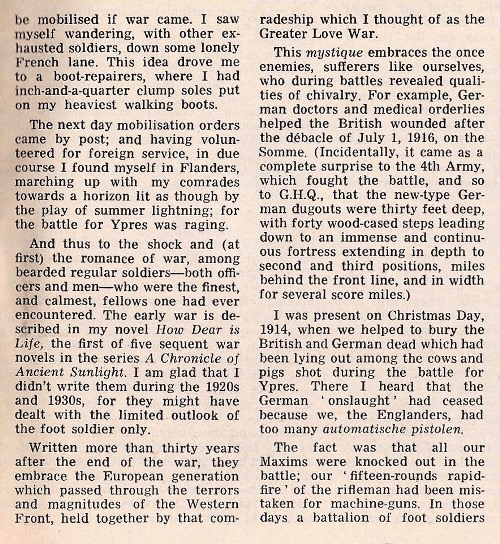

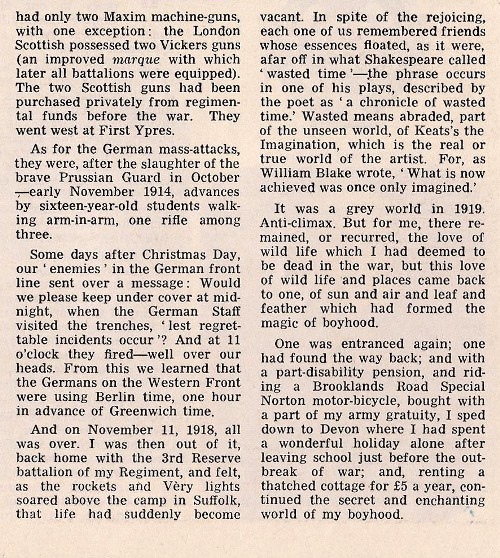

11 September: Radio Times to telephone re 500 words by HW about Armistice 50th Anniversary BBC TV Programme for 9 Nov.

12 September: I wrote & posted 800 words for above Radio Times article.

13 September: Revised copy of yesterday's Radio Times article posted to Radio Times.

HW had earlier received an invitation to a preview of the film:

But, as his diary shows:

10 October: To view film Armistice with Tristram Powell & Co. POSTPONED.

22 October: [HW was also dealing with galley proofs for The Gale of the World – the fifteenth and final volume of the Chronicle.]

To London. To telephone Tristram Powell re film of HW.

23 October: Tristram Powell

31 October: 12 noon. BBC Film Studios Ealing.

Mary Hewitt: Richard W. via train to London.

Also Lyn Hally [unknown to AW; together with two other names, also unknown]

HW to get bottle of champagne.

(This is for a preview of the film: Mary Hewitt was HW's first wife's cousin and bridesmaid at her wedding – HW maintained a contact with her. Richard is one of his sons.)

For the day of the actual broadcast, HW noted:

A month later he notes:

10 December: ? Pat Garland to lunch.

(On 19/20 December HW was filming for Westward TV – the channel for the West Country channel – at Ox's Cross, and noted: 'They recorded much autobiographical data about me.' His comments show he was rather taken aback by that.

*************************

No Man’s Land follows the format of The Survivor, broadcast two years earlier, in that Patrick Garland again acts as the largely unseen gentle questioner and prompter of HW’s memories – this time of the First World War. These are interspersed with Garland’s fine readings of some of Siegfried Sassoon’s war poems.

The film, in colour (the BBC’s colour service began the previous year, in July 1967), makes an effective and most moving commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Armistice.

It opens with HW reading from the opening paragraphs of A Test to Destruction, while the camera pans over the impressive interior of Ilfracombe’s cast-iron-framed glass-roofed pavilion, built in 1888 (now demolished):

In the winter of 1917–18 the Great War for Civilization – as it was generally accepted among the elderly and non-combatant of the Christian nations still engaged: Great Britain, France, Belgium, Italy, Germany, Austria, and the United States of America – was about to enter its penultimate phase on the Western Front.

This battlefield, upon which there had been continuous fighting for three and a half years, could be seen at night from aircraft as a great livid wound stretching from the North Sea to the Alps: a wound never ceasing to weep from wan dusk to gangrenous dawn, from sunrise to sunset of Europe in division.

As the great battles of the Spring of 1918 broke upon France and Flanders, so the flowers of the upland valleys arose with blooms as fugacious as human hopes for the outcome of the war, which, it was said everywhere, would decide the fate of the world.

When asked at the end of the reading how he felt at the war’s end, HW replies, ‘Sad, because all that had gone before, tremendous friendships and emotions, you see, had come to an end. . . .’

There follow shots of Ilfracombe as a brass band plays, panning round to 4 Capstone Place, as Garland comments: ‘Ilfracombe, a picturesque seaside resort in Devon, proves to be, rather unexpectedly, the winter home of Henry Williamson, novelist on animals and war. . . . Like so many fellow soldiers, Henry Williamson is unable, after fifty years, to shake off the burden of experiences suffered on the Western Front. His war-haunted mind is reflected in the poems of Siegfried Sassoon, almost as if the poet was speaking directly to him.’

Garland reads Sassoon’s sonnet ‘A Whispered Tale’, written in December 1916:

I’d heard fool-heroes brag of where they’d been,

With stories of the glories that they’d seen.

But you, good simple soldier, seasoned well

In woods and posts and crater-lines of hell

. . .

HW then talks of when he was in the trenches on Christmas Eve 1914, and how he’d heard ‘a beautiful baritone singing “Heilige Nacht”’; the subsequent meeting of English and German soldiers in No Man’s Land, and his realisation that both sides thought that God was on their side, and that each was fighting a righteous war.

Garland reads ‘Reconciliation’, written in November 1918, while the camera pans over various German pickelhauben and helmets on display in the Imperial War Museum in London:

When you are standing at your hero’s grave,

Or near some homeless village where he’d died,

Remember, through your heart’s rekindling pride,

The German soldiers who were loyal and brave.

. . .

HW recounts how, at Passchendaele, ‘it took four relays of stretcher bearers, four each to a stretcher, sixteen men with one stretcher, three hours to move a wounded man one hundred yards.’ Of the battle, he says: ’It wasn’t a question of gaining ground, but to knock your opponent out. . . . One [side] as brave and steadfast and clever as the other, and they were just battering each other to death.’

The scene switches to the great naval guns standing outside the Imperial War Museum, and then to the interior, with schoolboys examining guns and howitzers, while Garland reads ‘Song-Books of the War’, published in Sassoon’s Counter-Attack (Heinemann, June 1918):

In fifty years, when peace outshines

Remembrance of the battle lines,

Adventurous lads will sigh and cast

Proud looks upon the plundered past

. . .

Garland then asks HW what can it have been like to wait for an advance such as he described on the Somme [in his novel The Golden Virgin]; and HW replies with his impressions and memories drawn from his experiences on the Somme in early 1917.

Garland reads the sonnet ‘Dreamers’, written during Sassoon’s time at Craiglockhart in 1917:

Soldiers are citizens of death’s grey land,

Drawing no dividend from time’s to-morrows.

. . .

The film cuts to Ilfracombe Pavilion and a pianist playing to an open-air audience consisting chiefly of passers-by with their umbrellas up, as the rain patters down. She introduces herself as Nancy Mount (a regular summer entertainer in Ilfracombe, she was the sister of the formidable character actress Peggy Mount), and sings ‘Roses of Picardy’ as the camera focuses on HW, well wrapped up, listening in a deckchair; it then pulls back to reveal rows of empty, wet deckchairs. The singing fades as Garland reads ‘Blighters’, written in February 1917:

The House is crammed: tier beyond tier they grin

And cackle at the Show, while prancing ranks

Of harlots shrill the chorus, drunk with din;

“We’re sure the Kaiser loves our dear old Tanks!”

HW then recounts being sent on a short course ‘on what was known as “the accessory”’, actually chlorine gas; and describes how, when a transport officer in 1917, he witnessed the Battle of Arras, riding up in a snow storm just to watch it: ‘I went all over the place, and later – I should have been a war correspondent really – they wouldn’t have published my stuff for about thirty years afterwards, you see, because there was no propaganda in it, it was just fact. And I did publish it about thirty years afterwards.’

The film cuts to HW and Patrick Garland walking on Saunton Sands, while in voice-over Garland relates how HW was born not far from London, and that his affection for Devon stems from a summer holiday in 1914. HW then tells of this, his first visit to North Devon, in May 1914. Asked if he was on the Somme, HW replies simply, ‘Yes.’ (To clarify, while HW was indeed on the Somme, serving as the transport officer of 208 Machine Gun Company, and in France from 27 February to 8 June – see Henry Williamson and 208 Machine Gun Company – he did not take part in the Somme battles of 1916, unlike Phillip Maddison in The Golden Virgin.) HW then talks about The Golden Virgin, and the fact that Fourth Army staff had no idea that the German dugouts on the Somme were thirty feet deep in the chalk. In one of No Man’s Land’s memorable scenes, HW, reclining on the sand, uses a driftwood stick to draw in the sand the British and German lines, and, with the stick violently stirring up the sand, graphically illustrates the bombardment and subsequent events of 1 July 1916, the opening day of the Battle of the Somme. ‘That was the grave of Kitchener’s Army. After that things became pretty quiet. It was a pretty hard blow, you know, to – sixty thousand down, in half an hour, and the Big Push ending like that.’

Garland reads the sonnet ‘At the Cenotaph’:

I saw the Prince of Darkness, with his Staff,

Standing bare-headed by the Cenotaph:

Unostentatious and respectful, there

He stood, and offered up the following prayer.

. . .

Asked by Garland about the songs that used to be sung in 1913–14, HW reminisces about ‘the lovely summer of June 1914’, on the Hill, where his father used to fly big box kites in tandem on steel wires, and remembers ‘walking in flannels after tennis, with others on the Hill, and you’d sometimes hear groups of youths singing – I remember particularly, it was that song “We were sailing along on Moonlight Bay”.’ [He sings the first verse.] ‘Well, then we heard those songs again, you see, in Flanders, the troops would sing them when marching – so that linked up with my home – and I’ll always remember them, the golden years of my life, just before the war.’

HW then talks his experiences during the winter of 1914–15 in Flanders, where the water table was two feet below the surface; with trenches seven feet deep the troops had to cope with water ‘up to and above your navel, for three days and three nights, so cold, and raining . . . it was pretty bad.’

Garland reads the first verse of ‘Aftermath’ (March 1919), with the film showing poppies being assembled by hand, by old soldiers at a British Legion factory:

Have you forgotten yet? . . .

For the world’s events have rumbled on since those gagged days,

Like traffic checked while at the crossing of city-ways:

And the haunted gap in your mind has filled with thoughts that flow

Like clouds in the lit heaven of life, and you’re a man reprieved to go

. . .

HW is then shown leaves through a book of photographs from the war, including propaganda posters, and describes some of them; he talks about the massed attacks by the Germans in November 1914 at the First Battle of Ypres: ‘They were so dense that you couldn’t help but hit anybody, and your rifle got so hot the grease under part of the cover, the wooden cover, would run down – I was firing with my left eye, this way, my trigger finger – all the grease would run down, and I saw at the end of it, sweated out . . . a huge blister, where the boiling fat had gone down, firing cartridge after cartridge after cartridge . . .’ On looking at a picture of early tanks, he remarks, ‘God, they burned sometimes.’ And closing the book, he remarks, ‘The trouble is, the war achieved nothing.’

HW then takes up his first edition copy of Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That and reads an unpublished poem by Sassoon that was deleted from subsequent editions (see the Appendix below).

Garland comments, ‘And so, every winter, surrounded by the stuffed fish, paintings, wall photographs and other personal mementoes of his life, Henry Williamson celebrates Christmas in Ilfracombe, solitary, without festivities, keeping a kind of vigil. It reminds him of a time when, out of the wilderness of no man’s land, there suddenly appeared a kind of reconciliation.’ HW responds, ‘I couldn’t bear Christmas, and I would walk about by myself and eat the simplest food, bread and cheese – wearing the hair shirt, my friends used to say. But I wasn’t, I was going back to that very wonderful time, on Christmas Eve . . .’

As the film shows HW climbing up the dunes into Braunton Burrows, Garland again reads Sassoon’s ‘Aftermath’, this time the first and last verses:

Have you forgotten yet?

. . .

Look up, and swear by the green of the spring that you’ll never forget.

And HW, in voice-over, concludes softly: ‘I mean, they were the great years of your life, just as before the war was the great summer of your boyhood . . .’

No Man’s Land closes with Garland reading again ‘Song-Books of the War’, as young boys play around the naval guns and the huge shells that stand outside the Imperial War Museum:

. . .

Some ancient man with silver locks

Will lift his weary face to say:

“War was a fiend who stopped our clocks

Although we met him grim and gay.”

. . .

But the boys, with grin and sidelong glance,

Will think, "Poor grandad's day is done."

And dream of lads who fought in France

And lived in time to share the fun.

*************************

There are only two short notices, both in advance of the programme, in the Archive; there must surely have been some reviews:

*************************

Appendix: HW and Siegfried Sassoon

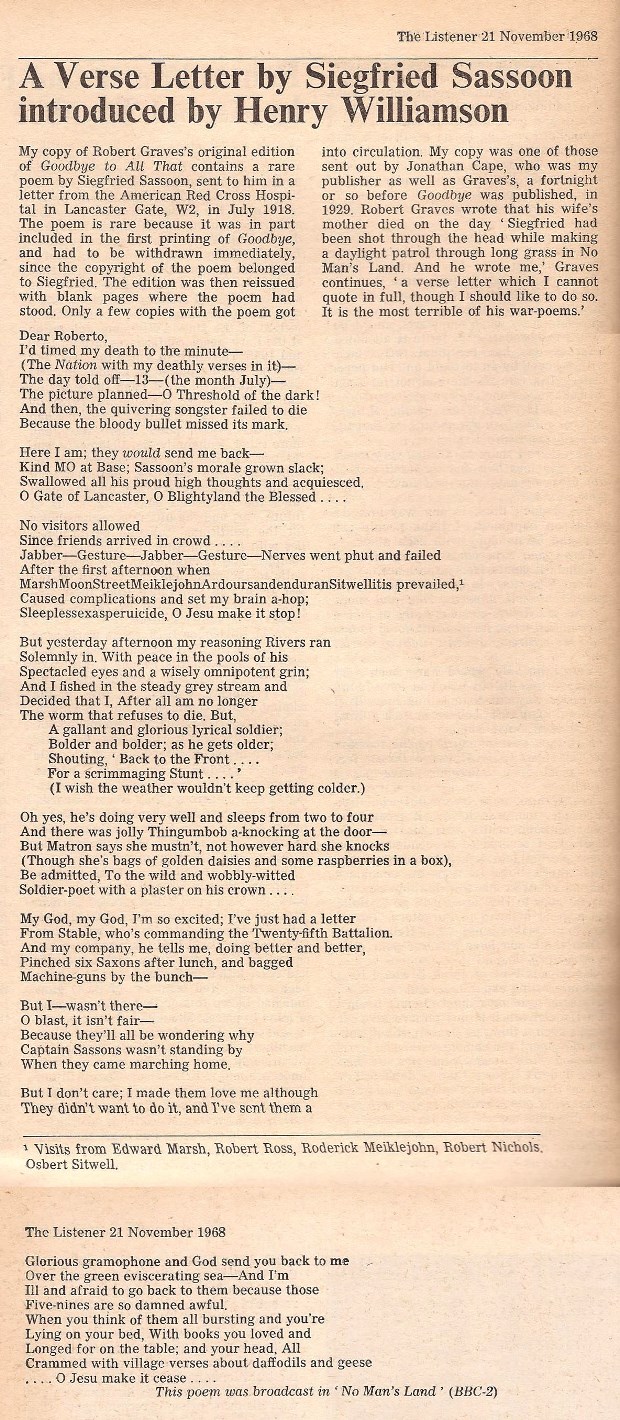

In the film No Man's Land HW reads out a particular poem written in July 1918 by Siegfried Sassoon (1886‒1967, soldier, poet, writer) while in the American Red Cross hospital recovering from a severe head wound, and which he sent to his friend and comrade Robert Graves. The poem was really a private letter written in verse sent to a friend, and not intended for public consumption. It is a very powerful, moving piece of writing – almost incoherent in its intensity (perhaps arising from a delirious state). It subsequently had a somewhat turbulent history.

In 1929 Robert Graves published his war memoir Goodbye to All That. The book attracted a great deal of attention, although actually it needs to be taken with more than a pinch of salt: the half-Irish, half-German Graves did not let 'truth' get in the way of a good story (as he later admitted). The book contained two particular controversial points concerning Sassoon. The first was that he wrote a great deal about Sassoon, including his breakdown and the subsequent period he spent at Craiglockhart, thus pre-empting (indeed, in effect stealing the material of) Sassoon's own book Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, which, as Graves knew, was in the process of being written. It was published the following year, 1930. Graves had of course been officially involved in supporting Sassoon through that terrible period of personal crisis.

However, over and above that, Graves printed in his own book – without permission – that highly personal verse-letter written by Sassoon from his hospital bed. Goodbye to All That had been printed and a few copies distributed for review purposes (HW was sent one of these original copies) before Sassoon learned about it. He refused to allow it to go ahead, and the printing had to be withdrawn. The book was subsequently published with blank pages at that point. It was the end of the friendship between Graves and Sassoon, although Graves, of a somewhat cantankerous disposition, seems to have quarrelled with many of his friends at this time.

A later, 1957, edition of Graves’s book was adjusted thus:

He [Sassoon] sent me a verse-letter from a London hospital (which I cannot quote, though I should like to do so) beginning:

'I'd timed my death in action to the minute'

It is the most terrible of his war poems.

Siegfried Sassoon, CBE, MC had already published (some privately) ten small volumes of poems before the First World War broke out. He had enlisted in the Sussex Yeomanry before war was declared, but broke his arm badly in a hunting accident and was not 'active' until late spring 1915, when he was commissioned into the 3rd Battalion, Royal Welch Fusiliers (as was Robert Graves) and sent to France. His brother Hamo was killed at Gallipoli, and his great friend (possibly the love of his life) was also killed. Sassoon was an extremely brave and impetuous soldier (he was nicknamed 'Mad Jack'), and was awarded the Military Cross in the spring of 1916 for bringing in under heavy fire a wounded lance-corporal who was lying close to the German lines. The story of his war service with all its problems is well-known, but full details of his life can be found in Max Egremont’s superb biography Siegfried Sassoon (Picador, 2005).

HW and Siegfried Sassoon had contact with each other in the late 1920s. When Tarka the Otter was first published, Sassoon had written a most charming letter to say that Walter de la Mare had introduced HW's work to him, and he enclosed a cheque 'with great pleasure for a book I intend to enjoy'. This was for the vellum-bound edition of Tarka, limited to 100 copies: he was sent copy no. 22. In his letter he asked HW to send some prospectuses so he could do a little propaganda on HW's behalf: a generous gesture.

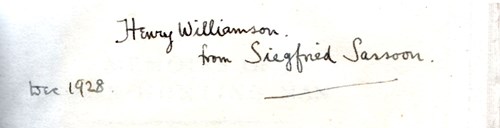

In due course Sassoon sent HW a copy of the limited edition of Memoirs of a Fox Hunting Man (Faber & Gwyer, 1928):

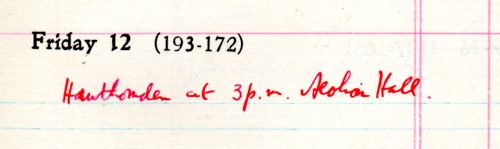

HW wrote to tell him the book was better than Tarka and deserved the Hawthornden Prize (which HW had just won for Tarka). Indeed, in 1929 Sassoon was the recipient. HW attended the prize-giving ceremony: Sassoon did not. HW's diary notes: 'Winner absent', and records the event in scrawled notes over several pages in his diary, written at the event, showing that Lord Lonsdale presented the prize, which was accepted by Edmund Blunden on behalf of Sassoon.

Further details can be found in Max Egremont's biography, where it is stated that Sassoon had suggested that T. E. Lawrence should present the prize, but he had refused to maintain anonymity and so it was arranged that Lord Lonsdale, 'a sporting philistine', should do the honours in his stead. This angered Sassoon, who felt it was a stunt, and he refused to attend.

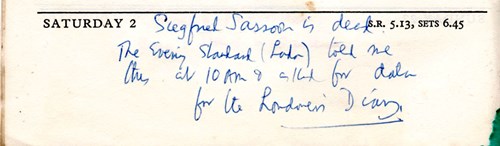

There is little further contact between HW and Sassoon, but when Sassoon died on 1 September 1967 the Evening Standard telephoned HW for comment, prompting him to write in his diary:

Opposite this entry is pinned a piece of paper with his initial thoughts:

The Evening Standard quoted him thus in that evening's issue:

At the time of the filming No Man's Land in 1968, only a few months after Sassoon’s death, he would have been very much to the forefront of HW's mind, and he surely thought to make a commemoration of a man whom he greatly admired for his courage as a soldier in the First World War, and as a poet and novelist: a man whom he would have regarded as a 'fellow spirit' – a friend.

HW read Sassoon's 'Verse-Letter' poem in the film, but left out two verses in the middle which would not have made sense in that context. In the BBC's weekly journal The Listener, a week and a half after the broadcast, the entire poem was printed, with an introduction by HW:

*************************