LOVE AND THE LOVELESS

A Soldier’s Tale

(Vol. 7, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight)

Whider thou gost, i chil with the

And whider y go, thou schalt with me –

from the Breton lay in English called Sir Orfeo

|

|

| First edition, Macdonald, 1958 | |

HW's photographs from 1917 (208 MGC)

First published Macdonald, 22 October 1958 (16/- net)

Panther, paperback, with small revisions, December 1963

Chivers reprint, by request of the Library Association, 1974

Macdonald, reprint, 1984

Sutton Publishing, paperback, 1997

Currently available at Faber Finds

Dedication:

In September 1916 Phillip is passed fit for Home Service and resumes his training at the Machine Gun Corps Training Centre at Grantham. When completed his unit is sent to France, and find themselves taking part in various attacks while preparations are made for the ‘Spring Offensive’ on the Hindenburg Line, May 1917. Phillip’s job involves the difficult and dangerous task of taking the limbers (wagons) with ammunition and rations up to the Front Line every night. He takes part in the attack on Messines Ridge, but various problems result in him getting adverse reports. He meets up again with Spectre West, who encourages him. On 1 July they move through Ypres for the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). The battle goes badly resulting in chaos. In November there is fierce fighting at the Battle of Cambrai. Phillip ends up exhausted suffering from fever and is sent back to hospital in England. When he recovers he is sent to join the Gaultshires at Landguard Camp at Felixstowe where the commanding officer is Lord Satchville (cousin of the Duke on whose moors he had roamed as a boy), whom he likes. The book ends with a New Year’s Eve party in London with Westy, which ends rather unhappily.

*************************

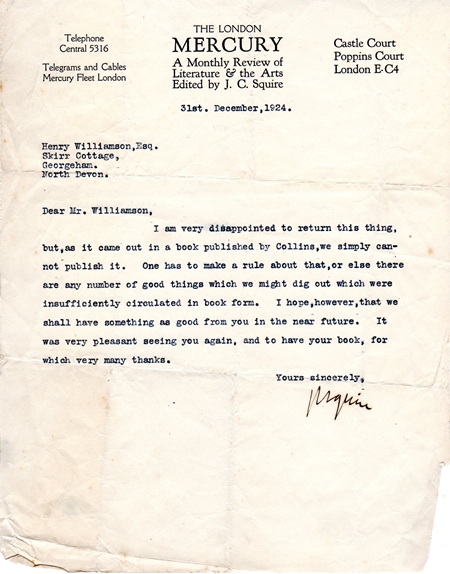

The dedication to Jack Squire (Sir John – he was knighted in 1933) was possibly long overdue. Squire had supported HW from a very early stage of his writing – they almost certainly met at The Tomorrow Club during 1920-21.

Squire was instrumental in putting forward Tarka the Otter for the Hawthornden Prize in 1928 and had introduced HW to the artist William Kermode, which resulted in their collaboration in The Patriot’s Progress. But the two men had lost touch over the years until, it appears, early 1958. Squire was born in Plymouth and educated at Blundell’s School at Tiverton (Devon). He considered himself a ‘Devonian’ and refers (in what is sadly a torn fragment of a letter written at this time) to ‘my Devon’. There is a long letter (14 quarto pages) written by HW to Squire dated 20 February 1958, which contains a large amount of information about his life and writing (with his usual complaints), but it was never sent – although a letter obviously was. The unsent letter ends:

But before the schnorrer, this totter [rag and bone man], this ragman pushes his barrow round the corner, let him say the principle thing that is on his mind: Deep and abiding affection for Jack Squire, with crystal-clear memories of the London Mercury office, the visits there, the encouragement, the help given, the spreading of the fame which came to a head with the Hawthornden Prize for Tarka - . . . That is why I have an abiding affection for Jack Squire.

Yours, Henry Williamson.

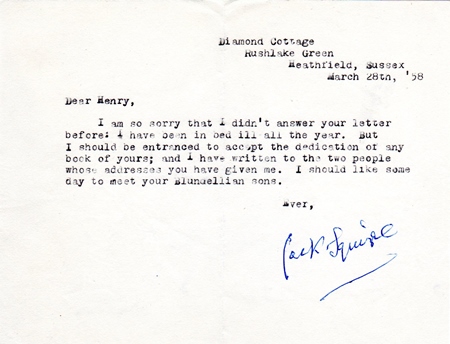

There is no indication whatsoever as to why HW rekindled this contact. My surmise is that he sent Squire a copy of the special HW issue of the Aylesford Review that had appeared that January. The torn fragment from Squire refers to the ‘brochure on your life and works’. HW probably had heard how ill Squire was (by then he was bedridden) via his various London contacts, and had thought a letter would be cheering. The letter that HW obviously did send Squire must have offered to dedicate this current book to him. Squire’s reply is dated 28 March 1958.

HW never knew whether his early mentor was able to appreciate the dedication. By October Sir John Squire was no doubt very weak. He died on 20 December. HW seems to have learnt of his death via the obituary in the Western Morning News, which he cut out and kept. He does not mention the death in his diary but added a brief note under the dedication in one of his file copies of the book which states that he had heard nothing from Squire about this – and then adding his date of death.

*************************

Whider thou gost, i chil with the

And whider y go, thou schalt with me –

from the Breton lay in English called Sir Orfeo

Somewhat obscure and chillingly mysterious, this intriguing quotation has a significance that needs some attention and explanation. HW must have known this poem very well to have quoted from it: it is not from a ‘run-of-the-mill’ source.

Superficially, taking the quotation as of being to do with Orpheus and Eurydice, one could (and indeed to some extent can) transfer that to Phillip and Lily Cornford, so tragically killed at the end of the last volume and who is often in Phillip’s thoughts, but the concept of the Sir Orfeo lay is very different from the classical story. I am quite sure that if HW had meant to refer to the Orpheus and Eurydice concept he would have used an appropriate quotation from that source. This is far more subtle an inference and has a deeper and wider significance.

Sir Orfeo is a verse romaunce of the early fourteenth century – to put that into context, around the time of Chaucer (1343-1400). A ‘lay’ was a narrative poem usually in rhyming couplets meant to be sung accompanied by a lyre. The form originated in France, thus ‘Breton’ – Brittany. It is a tale of chivalric deed. ‘Chivalry’ comes from the original ‘cheval’, meaning 'horse' (as does ‘cavalry’): and note that Phillip in this volume has a horse, Black Prince. The concept of Chivalry embodies the ideal knight, gallant, honourable, courteous, quixotic. The medieval knightly system had a religious, moral and social code.

The ‘romaunce’ tales of the medieval period have their own history and interpretation, much of which centres around what is known as ‘dream narrative’. (‘Dream narrative’ is too complicated to go into here but I have investigated this in relation to HW’s earlier work The Dream of Fair Women – see HWSJ 39, September 2003, AW, ‘Save his own soul he hath no star’, pp. 30-59.) Suffice to say here that the heroine Heurodis is abducted by the King of Faerie when she falls asleep, having previously dreamt that this is going to happen, which fits that theme.

The poem is based loosely on the classical story of Orpheus and Eurydice, but has a very different connotation. There is no tragic ending as in the standard Orpheus tale: Orfeo and his queen regain their kingdom. Sir Orfeo is an English king, so renowned for his harp playing as the best ever heard, who rules from Winchester (the ancient capital of Wessex). His beloved and beautiful wife Heurodis is abducted from beneath an ‘impe-tree’ as she sleeps by the King of Faerie.

(Scholars consider this to be a tree that has been grafted: ‘impa’ is Old English for young shoot – but also has the sense of scion (son of) and to me this would mean the ‘tree of the little devil (imp)’, i.e. a magic tree. The tree of the devil would surely be a yew tree which has connotations of evil – superstition states that if one falls asleep under a yew tree one will die (parts of the yew tree are highly poisonous). Indeed it is possible that the word ‘impe’ may actually be a mis-reading of an ancient name for the yew tree, most of which begin with an ‘I’, many ‘iw’ or ‘iu’, Old Dutch is ‘iep’, Old English includes ‘iuu’, iewe’, the Breton word was ‘iuin’.)

Leaving his kingdom in the care of a trusted steward the distraught Orfeo sets off on a quest or pilgrimage to find her. He wanders in the forest (wilderness) for ten years virtually as a hermit, living off berries, roots and bark, as would an animal. Eventually he catches a glimpse of his wife out hawking with sixty other ladies. He manages to follow her into the faerie kingdom, and bluffs his way past the door-keeper of a castle made of gold and crystal and glass by saying he has been sent to play his harp to the king.

Here he finds many people thought to have been dead but who are not – some drowned, some burned, some headless. (The allegory of this with regard to the First World War and HW’s writing is startlingly obvious.) Heurodis is once again asleep. Orfeo plays his harp, so charming the King of Faerie that he offers him a wish. Orfeo asks for the lady who had been taken from under the ‘impe-tree’.

The King of Faerie at first demurs but has to keep his royal word, and so Sir Orfeo returns with his wife to Winchester, at first keeping his identity secret but eventually revealing himself amid great rejoicing.

There is, I think, a further more subtle inference embodied by HW’s use here. The original concept of ‘Orphism’ embodies a sense of sin, a need for atonement, theory of suffering and death of a good (god-) man and a belief in immortality, and a final escape from evil – all very Christian virtues – which are all quite overtly present in Sir Orfeo. This means that we are actually looking at a quite deep religious concept underlying Love and the Loveless. It is interesting that several reviewers remarked on a religious aspect in the previous volume, The Golden Virgin. Here it is more hidden. This aspect is reinforced by the other source of almost exactly the same words as that quotation: they are to be found also in the Bible.

For whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God.

(or: For withersoever thou shalt go, I will go: and where thou shalt dwell, I also will dwell.)

The words are spoken by Ruth to her mother-in-law Naomi, whom she insists on accompanying from her own native land of Moab to Naomi’s home in Bethlehem. This is about loyalty, devotion, duty: of doing something that involves hardship because it is the right thing to do.

This covert religious theme is actually present in HW’s title, for those words ‘Love and the Loveless’ are found in a poem by Samuel Crossman:

My song is love unknown

My Saviour’s love for me

Love to the loveless shown

That they might lovely be.

O, who am I

That for my sake

My lord should take

Frail flesh and die?

These words were set to music by John Ireland in 1919, and is now a much-loved hymn. For HW, they would surely have had an association with the First World War.

However, there is an even more obvious source: I have found tucked away among the numerous items in HW’s archive material a copy of Pervigilium Veneris (Vigil for Venus), a Latin poem of about the fourth century which has a refrain:

Tomorrow shall be love for the loveless: tomorrow for the lover shall be love!

HW was given a copy of a privately printed limited edition translation of this work by its author, Geoffrey Higgens, in 1933 (unfortunately there is nothing to explain the background or connection between these two men), although HW may well have already been aware of the poem from earlier days as it is part of the classical heritage.

|

|

|

|

||

Pervigilium Veneris is quite complicated but is basically a song of spring (the festival itself was the first three days of April). Celebrating all the joy of spring and love, it calls on a large number of the gods to attend the festival but it particularly calls for a cessation of killing – that spring shall not be defiled by the blood of the slaughtered. ‘Love’ (Cupid) was to lay down all weapons in case he accidentally killed or harmed anyone – and Diana (goddess of hunting) was begged not to hunt; she was not invited in case her urge to kill creatures overcame her.

The work ends with reference to the nightingale’s song (‘fair Philomena’) and has a clear division between that joy and a plaintive sorrow:

Illa cantat, nos tacemos: quando ver venit meum?

(She sings, we are silent: when will spring come to me?)

And the poem, or plaint, continues (and ends, apart from another repeat of the chorus):

When shall I become as the swallow and renounce my silence? I am forgotten by my muse, nor does Apollo regard me: so Amyclae, being voiceless, was overwhelmed by silence.

Amyclae was an ancient (mythical?) city which was destroyed in war, its people killed or fled: Virgil speaks of ‘tacitae Amyclae’ (silent Amyclae). The commentator R. W. Postgate, writing in 1924, stated:

[This] is a lament, not for the death of a loved woman or friend, but for the death of a whole nation and a whole civilisation . . . [a point missed by most translators].

The connection to HW’s story here is painfully obvious. Its title and the accompanying quotation have a hidden depth of meaning that, once revealed, give a clear pointer to what HW wanted to achieve in this book: a lamentation for a spring and nations and civilisation killed by war – the British 1917 spring offensive.

*************************

By the time The Golden Virgin was published in September 1957 HW was already working on a very different book, A Clear Water Stream (Faber, June 1958). When he returned from his long holiday in Ireland in the summer of 1957 he also began work on volume 7 of the Chronicle, at this point provisionally entitled ‘A Test to Destruction’, the first mention in his diary being early December:

I posted 3 chapters – pp. 1-79 (inclusive) of A Test to Elizabeth Tippet.

On 5 December he was in London where he finalised the contract for A Clear Water Stream and had lunch with Eric Harvey of Macdonald’s, learning that The Golden Virgin had sold 6000 copies since publication.

Told him of No. 7, A Test to Destruction. He said I like the theme & title.

HW’s agent is now Cyrus Brooks at A. M. Heath.

On 31 January 1958 he recorded that he sent off his ‘first article for the Home (Co-op Manchester) Magazine. 500 words. £15-15-.’ This was the first of a monthly article from then until 1964. These articles have been published in From a Country Hilltop, ed. and introduction by John Gregory (HWS, 1988; e-book 2013).

There are some quite detailed diary entries concerning the writing of Love and the Loveless which gives an insight into his overall modus operandi – and his huge workload.

On 4 February he received the contract for No. 7 novel (but does not give details).

5 February: Finished Chapter 11 – ‘Spectre Speaks’ [becomes Ch. 12, ‘Phillip Meets an Old Friend’] this evening. Very hard chapter, result of much reading and searching & over-reading. I am very tired, have been on this single thread, like a caterpillar eating upwards on a silken line, for many many thousands of days & nights now. I have headaches at times.

6 February: Working on Chapter 10. The work has to be pulled apart, cancelled in places, re-adjusted many times. Usually when a chapter is done I see how it should have been done. . . . Began Chapter 11 at night – two sentences.

9 February: Worked all day on Chapter 11. Didn’t get far. Rearranged 9 pages done so far, after much research.

He had also been back and forth to the cottage he had bought in Ilfracombe, arranging for repairs and buying furniture at various sales. All this was a great source of irritation, with the spending of much nervous energy.

11 February: Finished Chapter 12 – It would not fit into my plan but wrote and adjusted itself en route pp. 294-313 ‘The Fox Out-foxed’. [became ch. 13 when published].

18 February: I decided at 6.30 pm, after reading the reconstructed first part of chapter 16 of No. 7 to not pursue the theme of destruction to Oct. 1919, but to end it in 1917.

Chapter 16 as planned – Westy wounded up by Passchendaele, Ph. struggle to get to G.H.Q. as ordered by Westy. Seeing Haig & return. Then to Cambrai, the advance & the chop, himself in pyjamas & trench coat fleeing with German flare pistol & cartridges in his haversack. Arrest & goes sick. P.U.O. [louse fever] like Downham. So to England, convalescent home at Falmouth . . . On leave, Ph, meets Desmond & Gene. Party in Picadilly – not Flowers - & all back to the flat for Christmas & sending up hot-air balloons on Christmas Eve with Very lights. Ends with orders to report to 3rd Gaultshires. “Thank God I’ll at least be with a decent crowd.” (end of book).

At the end of February proofs of A Clear Water Stream arrived, were dealt with over two days and sent back – as also the ‘May’ article for the Co-op Magazine. On Sunday 2 March HW recorded he had got to near the end of Chapter 15 of 'Test'. The next day, stating that he is upsetting himself by diverting from his original plan, he decided to scrap chapter 15 – ‘When Phillip returns to the Gaultshires & revert to the plan’. There was a short interlude in London where he checked the corrected proofs of A Clear Water Stream and recorded an unscripted 40-minute talk for the BBC about John Murry and the Adelphi.

Tuesday 11 March: Began, after agonising (head aching) interval to recast Chapter 15 of No. 7 novel. I strayed off the planned path.

12 March: Working all morning on Chapter 15. Wrote 800 words review of Leslie Reid’s Earth’s Company in afternoon, for the final issue of ‘Time and Tide’ on 22 March.

13 March: Almost finished the recast Chapter 15. [But he is thrown by problem with Christine and also has a cold; and has received a very critical letter from the north country writer Crichton Porteous telling him his] novels are so dull, almost unreadable . . . Rather hit me . . .

15 March: Slogging on with novel. Find it very hard to maintain confidence. Still altering & trying to arrange Chapter 15. [In the printed book this is the ‘Mutiny’ chapter.]

On 18 March he sent off chapter 15 for typing and started chapter 16.

20 March: Changed plan of novel. Am on Chapter 16 – Spectre’s walk with Phillip to Passchendaele; his wound: & instructions to Phillip to carry his message – report to G.H.Q. at Westcapelle.

21 March: Working, working, working. The new plan shortens book & makes the old title obsolete. Novel to end in 1917, after Cambrai (Chapter 17) & P’s escape from near-prisoner & with PUO gets home to England, & returned to Gaultshires. [PUO = Pyrexia of Unknown Origin: and was louse or trench fever. In Love and the Loveless, p. 355, this is misprinted as 'Perdoxia'. HW has a correction note to change it to 'Pyraxia', but my dictionary spells it with an 'e'.]

On 28 March he posted off Chapter 16 for typing and revises earlier typed pages.

30 March: Writing Chapter 17 “Mouse to Lion” [is ch. 18 in printed version]

31 March: Writing chapter 17, first rough draft. [+ 800 words for the Co-op Magazine].

2 April: Revised Chapter 17 and in afternoon posted it to typist. [Plans to have a break – go to Bungay – collect Richard and books] before beginning the Cambrai (Nov. 1917) Chapter, to be followed by two chapters (19 & 20) to end the book.

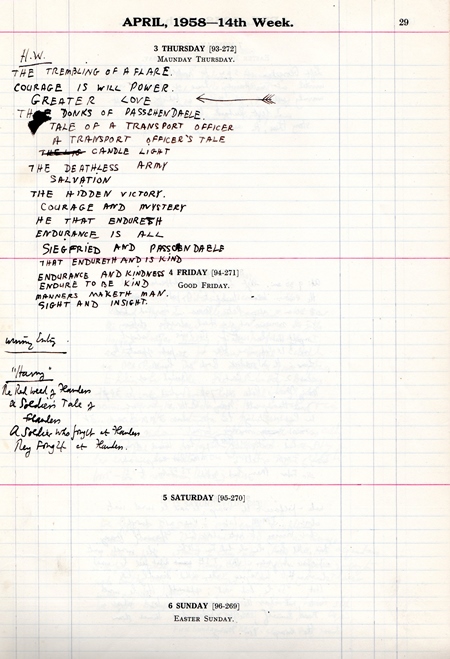

The title A Test To Destruction is now unapplicable to the present novel.

So he needs a new title; and holds a little family competition:

It will be noticed that the actual title used is not among these! ‘Love and the Loveless’ had originally been meant as a sub-title for the previous volume – and for some reason it got left out. HW’s diary entry of 20 November 1957 notes corrections for The Golden Virgin to be made and sent to Macdonald with a request to restore the sub-title ‘Love and the Loveless’, but that did not happen. So of course he already had a ready-made title for the present volume, and had already decided upon it: the little family competition was no doubt a charade to have some fun. ‘Love and the Loveless’ was anyway far too important a concept to be merely a sub-title, as has been explained. The discarded ‘Test’ title then gets transferred to the next volume.

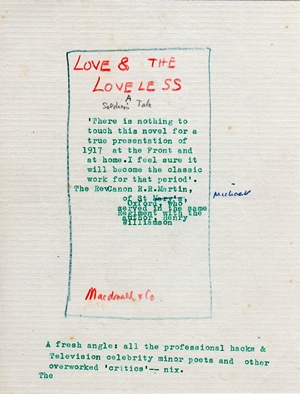

There is also an extraordinary file of HW’s own sketches for the cover design of this book (and some by his wife): thirteen pages of them over the best part of two weeks (24 June–4 July). This task obviously had great significance for him and caused some anguish of spirit! There is unfortunately nothing in the files to explain the background of this quite amazing attention to detail. One wonders what Broome Lynne, the artist who designed the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight covers, made of it all, but he certainly took on board the main concept. That handclasp is of two males – two soldiers. It gives emphasis to the concept of 'love and the loveless' as being about the comradeship of soldiers (perhaps also representing the opposing armies); and NOT Phillip's grieving for the dead Lily.

A selection of these sketches is given on a separate page.

HW was at Bungay for a week, returning to Devon with his son Richard on Saturday, 12 April. The following day he sent off a 700-word article ‘Road to the West’ to Macdonald Hastings for the Farmers’ Weekly Show Number (for which he received 35 guineas). He worked on the revisions for ‘No 7, reading it to Richard & Christine each evening’. (There is no indication of how long Richard stayed!) HW now records continuous rows with Christine because she won’t deal with the Ilfracombe cottage (which he never wanted), the architect’s plans to rebuild the kitchen and buying of furniture, etc. This is still going on in June. In August the plans are finally sent to Ilfracombe Council.

On 30 May he recorded in his ‘Tablet’ appointment diary:

Finished No. 7 Novel (Love & Loveless) today thank God. Now for a spell of outdoor work.

On 17 June he attended Lord Fortescue’s Memorial Service at Exeter at 3 p.m. (Fortescue had been his landlord at Shallowford, Devon, in the 1930s, and was the older brother of Sir John Fortescue who had written the Introduction for Tarka the Otter.) On 4 August HW sent a copy of ‘John Bull’s Schooldays’ to the Spectator [published as ‘Out of the Prisoning Tower’, 22 August; collected in Indian Summer Notebook, HWS 2001; e-book 2013.]

15 August: I have the proofs of No. 7.

In September Ernie Brown, whom he had known as a child in 1916-21 when living at Skirr Cottage in Georgeham, and who features in the early village stories, is engaged to do the work on the Ilfracombe cottage because his tender was the cheapest: there are, inevitably, constant problems over this work! The unsent letter to Ernie shown below has on its reverse side a suggested 'puff' for the novel, not taken up by Macdonald:

On 9 October he gave the prestigious Wedmore Memorial Lecture to the Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature, 'Some Nature Writers and Civilisation', his subject being Richard Jefferies and W. H. Hudson (collected in Threnos for T. E. Lawrence & Other Essays, HWS 1994; e-book 2014).

Wednesday, 22 October: Love and the Loveless published today. Copies have been, or will be, sent to Sir John Squire, Denys Val Baker (his excellent article in W.H. Smith’s Trade News), Lords Hankey & Moyne (Bryan Guinness), Fr. Brocard Sewell, O. Carm., Lt. Gen Sir Brian Horrocks, F.M. Lord Montgomery.

In his ‘Tablet’ appointment diary, 3 November: ‘To begin re-start No. 8 today.’

14 November: Deep depression over Love & Loveless – unreviewed. [Not totally correct but reviews were quite slow in appearing and HW obviously felt great disappointment at this point.]

*************************

Love and the Loveless is divided into four parts: Part One: ‘The Black Prince’; Part Two: ‘‘All Weather Jack’ Hobart’; Part Three: ‘‘Sharpshooter’ Downham’; and Part Four: ‘’Spectre’ West’.

Part One opens in September 1916 as Phillip travels to rejoin the Machine Gun Corps Training Centre at Grantham. (A Medical Board passed HW fit for Home Service only, and he returned from convalescent leave on 23 October 1916.) Phillip applies for the Transport Course, i.e. to train as a Transport Officer. Among other training he is sent to Riding School where he learns how to deal with all aspects of horses and mules as will be necessary at the Front. (See also AW, Henry Williamson and the First World War, Chapter 5, ‘Transport Officer at the Front’, pp. 69-132, where full details of HW’s own training etc. are described; this training in animal husbandry stood HW in good stead in later years when he bought the Norfolk Farm.) He meets Yeomanry Captain ‘All-Weather Jack’ Hobart, a capable officer and splendid man (based on Captain Roy Colgate, see AW, Henry Williamson and the First World War, p. 186), with whom he strikes up a friendship and with whom he goes hunting. We also meet Teddy Pinnegar (also based on a real person, but whom HW did not actually meet until many years later on the Norfolk Farm – but whom he added in here for structural purposes). There are various authentic scenes of the off-duty high-jinks that the various characters get up to.

Phillip obtains ‘Black Prince’, a lively black gelding of sixteen hands with some Arab blood. There is a superb description of the moment that he felt at one with his horse:

He experienced a new power upon himself, accompanied by a singing joy. It was not just confined to the feeling that he could ride, but to other things in life. . . . As he fled across the park he felt that he had come through the shadow that had always lain upon his life. . . . he felt he and the gelding were great friends already. . . . Black Prince is intelligent, Phillip thought; he knows, as Lily had known.

This new achievement gives Phillip confidence within life itself (today an obvious aspect of modern psychology). This (and the ensuing scenes at the Front) is also one of the first genuine descriptions of the tremendously important part played by horses and mules in the First World War.

When training is completed the men are given embarkation leave. Hobart takes Phillip to London in his ‘Racing Merc’ (Mercedes sports car) to the Flossie Flowers Hotel, to meet up with Hobart’s rather dashing girlfriend, Sasha. (For background on the Flossie Flowers Hotel, see John Homan, ‘Flossie Flowers Revealed’, HWSJ 22, September 1990, pp. 42-3.)

Part Two opens in mid-December 1916 as the men entrain with mules and horses to France and the Front Line. (HW embarked in similar fashion in February 1917. He took the time back in the novel so he could include wider aspects of the war.) On Christmas Day Phillip rides, on Black Prince, into Albert, seeing the Leaning Virgin, and then on to Mash Valley (where he had been wounded on 1 July), where nothing is recognisable: a wasteland. He grieves for the dead, as HW grieved every Christmas throughout his life.

The spirit of a million unhappy homes had found its final devastation in this land of the loveless.

Phillip’s work involves taking limbers (wagons) with ammunition and rations up to the Front Line every night, difficult and frequently dangerous work, for the teams of men and horses have to progress in the dark through the mud swamps under constant shelling. There is a succession of problems with men and horses (the veterinary rules were very strict indeed – and the army veterinary officer did not like Phillip). The men are involved in a series of smaller attacks moving forward as the Germans retreat, while preparations for the spring offensive continue.

Phillip is ever conscious of the presence of nature even within this desolate landscape. He notices flowers, and birds, nightingales and skylarks, and even mallard flighting over at night.

They would be nesting soon, he thought. For birds, the spring meant love – for men, the spring offensive, and the kiss of bullets.

There we have a direct reference to that Pervigilium Veneris poem:

Spring! Spring is of youth! Spring is now singing!

Spring is the birth, the birth of the world!

In Spring Loves unite,

In Spring the birds mate and the woodland

Unbinds her green tresses in the rain.

Spring in the trenches of the Front Line of France and Flanders, however, meant only death and destruction.

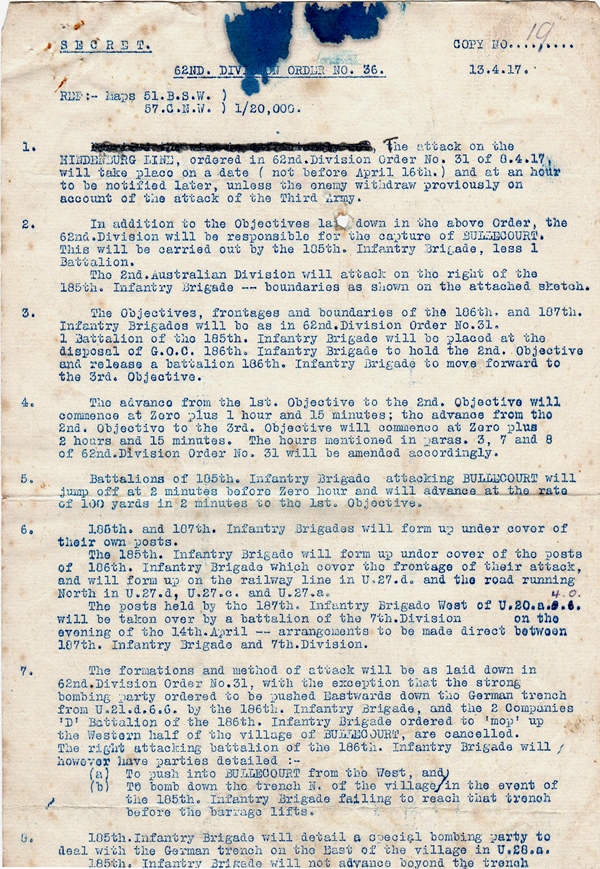

There is a major attack on the Hindenburg Line planned for the beginning of May, which results in another sprawl of dead and maimed. HW’s various detailed field notes made in 1917 at the time of this attack can be found in AW, Henry Williamson and the First World War. His actual orders for the attack are reprinted facsimile in HWSJ 34, September 1998; the first page of these is shown below, together with the Order of the Day:

Then at the end of May Phillip is involved in a further attack on the Messines Ridge held by the Germans. In a second attack which goes wrong, Phillip loses two mules and a driver on his nightly run, and later learns that Captain Hobart has been killed. Pinnegar takes temporary command but the new CO is Major Downham, who had been in the Moon Insurance Office where Phillip worked before the war, and does not like Phillip. To Phillip’s dismay, Downham immediately commandeers Black Prince for his own use.

When the company goes out of line, Phillip is sent off on a signalling course which he fails and from which he is returned fairly quickly, and so is reprimanded over adverse reports. He goes back to England for ten days’ leave with the unhappy Bright, whose plight is based on true story, where he asks to be transferred back to the Gaultshires.

Phillip, during this period, served with the fictional 286 Machine Gun Company. HW actually served with 208 Machine Gun Company, and his photographs of 208 MGC, in an album in the Literary Archive, are shown on a separate page.

On return to France the situation is the same, but going into Poperinghe he sees Spectre West, who is giving a staff lecture on Ypres and battle tactics. Afterwards the two men meet for a meal. Westy states that he had once had ambitions to write a War and Peace for this age:

‘But it will take thirty years before anyone taking part in this war or age will be able to write about the war [or its wider aspects] . . . ’

As Westy is Phillip’s (HW’s) alter ego, this is a pointer laid down by HW for his own work not begun until thirty years after the events: the War and Peace analogy being an ongoing theme which had pre-occupied HW from the earliest days of his writing career. Their conversation allows HW to include philosophical discussion of war. Westy ends:

‘Remember this, “He who loses his life shall save it” [quotation from Matthew 10, v. 39]. Put duty before self! That alone will carry you through to the end.’

This reinforces the covert religious aspect of the novel.

On 1 July the men move through Ypres for the Third Battle of Ypres – Passchendaele. Phillip, not trusting his sergeant to be able to cope, now takes the limbers with rations and ammunition up to the Front Line every night himself. The battle goes very badly with the tanks bogged down in the mud. Chaos. Phillip’s horse (not Black Prince but a mare) is hit and he has to shoot it. As he goes forward:

To the right, a few miles away, tremulous piano-playing fingers had changed to a flight of butterflies with wings overlapping one another, trembling and blazing in radiance above the row of lily flares . . . Soon they were in full view of the Steenbeek valley . . . the luminous butterfly wings still rose to the zenith above the Menin Road where ruddy splashes and sparks revealed the fall of British shells among the German batteries on the Gheluvelt plateau. The tempest of Hell!

However, Downham, regardless of the problems they had encountered, is furious because they are late arriving. (Later, Pinnegar says that Downham is useless.) One of Phillip’s drivers is killed by a shell. The men manage to bring his body back:

The truth was that it did not seem right to leave Daddy M’Kinnell in that lonely waste of mud and water.

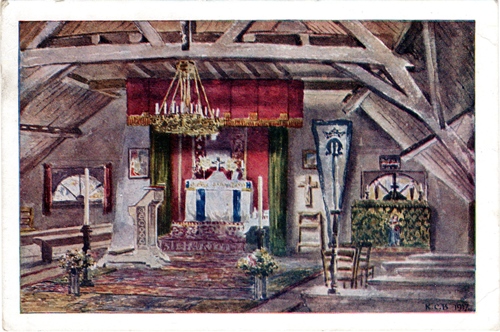

Spectre takes Phillip to Tubby Clayton’s chapel in the upstairs hayloft in Poperinghe, in a very beautiful passage in the midst of carnage and chaos of war:

They stopped outside a tall grey house, on the door of which was a notice, All rank abandon ye who enter here. Inside on the wall was a painted hand pointing to the door . . . They went up a wooden stairway, and then up another flight, and so along a bare wooden corridor . . . up some steep open treads, and so into a large loft with beams and posts holding up the roof.

Phillip saw it was a chapel. From the king-post was suspended a chandelier with a ring of candles. Beyond, against one wall, was a red altar cloth, with green borders. Another red cloth, with gilt tassels, hung from a beam above the altar. The space before the altar was flanked by two massive candles on wooden stands. Beside each was a bowl of flowers. A carpet covered the centre of the floor. There were a few plain wooden chairs and benches, and two shrines, one on either side of the altar, below semi-circular windows. There was a lectern painted white. . . .

The air shivered with deeper undertones of heavy howitzers, pounding away in the Salient. Then the sun came out behind a cloud and light shone whiter through the semi-circular windows, Here men had clumped up the steep and narrow stair, borne up by Hope, seeking solace at the verge of unutterable Darkness. . . .

Phillip thinks of Father Aloysius, and Mère Ambroisine and of Francis Thompson, and recites one of his poems to himself. [HW’s Aunt Mary Leopoldina – Theodora Maddison in the Chronicle – had given him a book of Francis Thompson’s poems just before or at the beginning of the war. This poem echoes the quotation from Matthew that Spectre West had used earlier.] Spectre explains the background of the chapel to him.

(HW has a diary note made – in a separate diary otherwise blank – on Monday, 10 February 1958 in the Athenaeum, Barnstaple (very precise!):

Gilbert Talbot fell in flame attack at Hooge in July 1915 [see The Wet Flanders Plain entry, where HW visits this chapel in 1927]. Son of Bishop of Winchester. Lt. R.B., [Rifle Brigade]. ‘Talbot House’ a club in Pop. opened in Dec. 15 in his memory. Tubby Clayton, padre C.E. It was not Toc H in 1917. This name arose in 1920 as there was already a Talbot House in the Black Dog.

A small detail but checked thoroughly!)

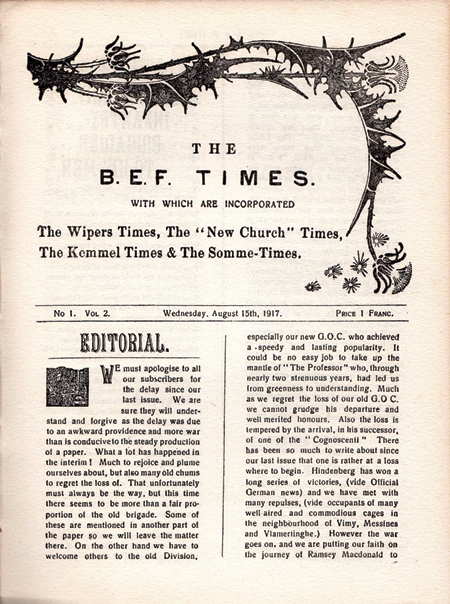

To get rid of him, Downham sends Phillip on a course at No. 3 Infantry Base Depot, Etaples. A respite is given (as it was throughout the Front), with amusing extracts from the B.E.F. Times which Phillip, on the train now, sees for the first time.The archive contains HW's copy of the 1928 reprint of this publication which had been so important for the morale of the troops.

(HW later wrote the Foreword for The Wipers Times (Peter Davies, 1973), in which he includes a description of the 1914 Christmas Truce, and states that these front line publications were:

gentle and kindly in attitude to what was hellish – and this attitude, its virtue, was extended towards the enemy. It is a charity which links those who have passed through the estranging strangeness of battle . . .

The full Foreword is collected in the revised e-book edition of Threnos for T. E. Lawrence & Other Essays, HWS, 2014.)

Etaples is described as being like a POW camp, surrounded by barbed wire fences. The main feature is the Bull Ring where: ‘thousands of men daily received intensive training with bombs, rifle-grenades, Lewis gun and rifle fire and bayonet practice. . . .’ There is also the appalling and degrading ‘Punishment Compound’.

The whole place was rancid with subdued anger . . .

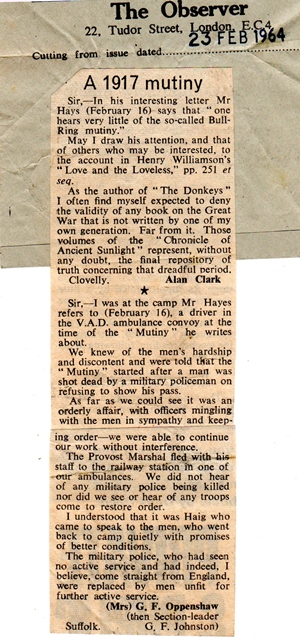

This is the all-important Etaples ‘Mutiny’ chapter, over which, as we have seen, HW took so much trouble – and as I have pointed out, he appears to have been the first to put this episode into print.

Phillip meets Major Colin Traill, a gentle man who likes poetry. (HW actually met Traill when both were convalescent at Trefusis in Cornwall where they become friends. Traill had been wounded at Oppy Wood on 3 May 1917 and awarded the MC. He was later killed in action – see HWSJ 43, September 2007, Anne Williamson, ‘"My Friend": Major Colin B. Traill, MC’, pp. 92-3.)

|

|

|

|

Major Colin Traill, MC (photograph taken at Trefusis in July/August 1917) |

Colin Balfour Traill was killed on 28 June 1918, aged 23. He is buried at Le Grand Hasard Cemetery, Morbecque. |

Trouble escalates, coming to a climax when a sergeant in the Military Police accidentally shoots a Gordon Highlander when a bullet ricochets. A semi-riot occurs. Troops move in to guard prisoners. At the resulting courts-martial the ringleaders are sentenced to death and imprisonment. This episode was completely hushed up at the time for the purposes of morale, and little had ever been known publicly. HW first mentions this in The Patriot’s Progress, published in 1930, but here the description is much more detailed. (In a letter to T. E. Lawrence dated 24 March 1930, after the publication of The Patriot’s Progress, HW wrote: 'Damn! I wanted 60,000 words recreating the Etaples mutiny: now I've pooped it off in 600 words.')

(The later BBC programme The Monocled Mutineer, broadcast in 1986, claimed wrongly to be the first revelation of this episode: see HWSJ 15, p. 54 and HWSJ 16, pp. 37-8.)

His course over, to his relief Phillip is told to return to his unit where he finds Pinnegar in charge. Downham has gone back to England with PUO (louse or trench fever), having totally blotted his copybook anyway. Phillip gets Black Prince, his horse, back and goes off for a ride.

Phillip returns to Poperinghe, where he goes to the rue de l’Hôpital, and again climbs the steep flights of stairs to the hop-loft chapel. A service was being held:

Now with feelings of optimism and even joy, he knelt down, and became clear and simple.

Afterwards he talks to the padre (Tubby Clayton): ‘Thank you for making this oasis for all of us.’

The story continues with another attack with detailed descriptions, much of which can be found within HW’s Field Note Books of 1917 (see AW, Henry Williamson and the First World War), although taking place earlier than in the novel. Phillip meets up again with Douglas, originally in the London Highlanders with him in 1914, now wounded with a bullet through his shoulder (Douglas Bell; see A Soldier’s Diary of the Great War.)

Westy then takes Phillip with him on an intelligence-gathering mission during which he is badly wounded and sends Phillip back to HQ with the urgent information, insisting he leave him lying there. This does not prove an easy task in the chaotic conditions, and Phillip ends up ‘stealing’ someone else’s horse to achieve Westy’s orders. Once he has handed over the information he is interviewed by Field Marshal General Sir Douglas Haig who is courteous and kind. When this is all over and he gets back to his unit he goes for a ride on Black Prince to calm himself.

The action moves inexorably on to the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917, involving huge numbers of tanks. The new Brigadier is the ‘Boy General’, the legendary Brigadier General Roland Boys Bradford, VC, MC, who was killed in action on 30 November 1917, aged 25.

|

|

Bradford's grave at Hermies British Cemetery, situated between Cambrai and Bapaume |

Pasted into HW’s own copy of Love and the Loveless are two Remembrance Notices for Roland Bradford – one from The Times, 1 December 1958 (HW’s birthday, which would have made it very poignant for him); the other unmarked, but noting the death of the three brothers: a family tragedy.

The fighting is desperate and Phillip’s work is intense. Bourlon Wood is taken at great cost, but the attack on Bourlon village fails. There is a gas attack and the men have to fit masks on to the animals before donning their own. Phillip manages to lose the way to Graincourt and ends up way beyond it at Le Quennet Farm, almost in the German line (these are all famous landmarks within that battle scenario). That night the Germans break through, so there is yet more chaotic fighting and movement.

(The map is reproduced from the useful and interesting article by Peter Cole, 'The 286th Machine Gun Company' in HWSJ 18, September 1988, pp. 30-37.)

Phillip finally collapses with exhaustion and fever (PUO – see HW’s diary notes). The doctor won’t let him move so he cannot say goodbye, a great sadness because:

he could write to Teddy [Pinnegar], to Nolan and to Morris; but nothing could be done about Black Prince.

He is sent back to England to hospital where he learns with great relief that Westy was found and is safe. On being discharged he is given three months’ Garrison ‘B’ duty (i.e. not fit enough for Front Line service).

(HW was actually gassed at Bullecourt on the night of 7/8 June 1917 taking a limber up to the Front Line, when one of the mule drivers, Private Frith, was killed by a shell within feet of him: he was hospitalised, returned to England and eventually sent to Trefusis at Falmouth, Cornwall, to convalesce, where he began to write – almost certainly as therapy. Eventually he rejoined the Bedfordshire Regiment at Landguard, as did Phillip.)

Phillip is sent to join the Gaultshires at Landguard Camp, Felixstowe (Suffolk), where he learns Westy is also currently stationed but has gone to London to receive yet another decoration. The commanding officer is Lord Satchville (Lord Ampthill in real life), cousin of the Duke of Gaultshire (Duke of Bedford) on whose moors Phillip/HW roamed as a boy. (All this echoes the real life situation – other than the fictitious ‘Westy’.)

The final scene involves a New Year’s Eve party in London attended by Westy and Phillip at the Flossie Flowers Hotel, where Sasha attaches herself to both men and so divides them. Phillip thinks it is the ‘Lily’ situation all over again. Westy leaves: shortly after so does Phillip. The reader is left on a ‘cliff-hanger’ wondering what the outcome is to be!

*************************

Index and Chronology to Love and the Loveless: Maps and Chronology and Index

Between 2000 and 2002 Peter Lewis, a longstanding and dedicated member of The Henry Williamson Society, researched and prepared indices of the individual books in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight series (the first three volumes being indexed together as 'The London Trilogy'). Originally typed by hand, copies were given only to a select few. His index to Love and the Loveless is reproduced here in a non-searchable PDF format, in two parts, with his kind permission. It forms a valuable and, indeed, unique resource.

*************************

Click on link to go to Critical Reception.

***************************

The dust wrapper of the first edition, Macdonald, 1958, designed by James Broom Lynne:

HW's comments written on the blurb:

Other editions:

|

|

|

|

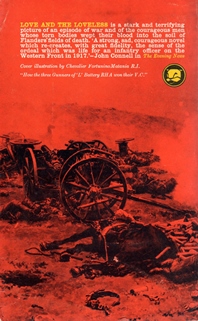

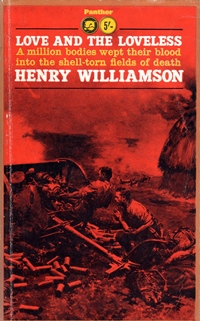

Panther, paperback, 1963. The edition featured this striking wrap-round contemporary drawing by Chevalier Fortunino Matania R.I., entitled 'How the Gunners of 'L' Battery RHA won their VC'. |

||

|

|

Cedric Chivers, for The Library Association, hardback, 1974 |

|

|

|

| Macdonald, hardback, 1984 | Sutton, paperback, 1997 |

The Macdonald cover features a detail from 'Epehy 1918', by Haydn R. Mackey (1883-1979) (Imperial War Museum). The Sutton cover is a detail from 'The Triumph of Death' by Pieter Brueghel the Elder (c.1815-1569).

Back to 'A Life's Work' Back to 'The Golden Virgin' Forward to 'A Test to Destruction'