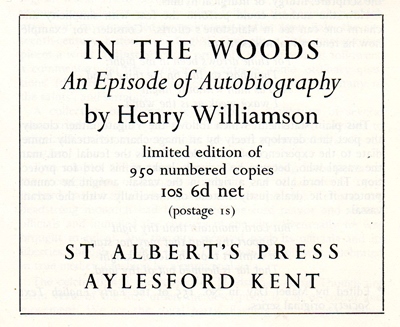

IN THE WOODS

|

|

| St Albert's Press, 1960 | |

|

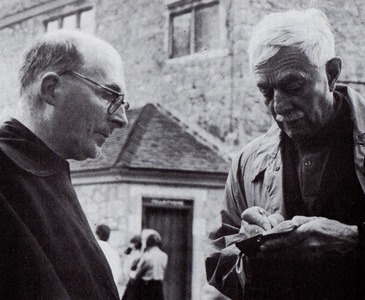

Fr Brocard Sewell and St Albert's Press

|

|

|

|

|

| HW’s further involvement with Aylesford Review literary events |

First published St Albert's Press

Limited edition of 1,000 numbered copies, nos. 1-50 signed by the author and bound in cloth; nos. 51-1,000 bound in paper covers

(Although the imprint states 1960, the book was actually published in early 1961.)

St Albert's Press was in the domain of the English Carmelite Brotherhood and was established in 1955 to print the magazine The Aylesford Review from Aylesford Priory in Kent. The magazine was the idea of, and was edited by, Father Brocard Sewell (1912‒2000). The Press (which was actually transferred to Llandeilo, Wales in 1959) also printed and published books of a suitably serious religious/literary content. For more information, see Brocard Sewell, 'The Aylesford Review', HWSJ 5, May 1982, pp. 23-9, which includes a 'Checklist of HW articles in The Aylesford Review'. Further details about the history of the Press will be found in an article by Fr Brocard published in John O'London's Weekly in 1961, reprinted here in the Appendices.

HW first met Father Brocard (a name taken on entering the Brotherhood in the early 1950s: he was christened Michael Seymour) in early December 1957. Fr Brocard had written to HW about his recently published novel The Golden Virgin. Although The Aylesford Review had originally been intended as a vehicle for religious articles, Fr Brocard had quickly widened its approach to include literary material. He was currently planning a special issue devoted entirely to HW's work: 'Henry Williamson: A Symposium & Tribute', The Aylesford Review Vol. II, No. 2, Winter 1957/8. Apart from a five-page editorial by Fr Brocard, the essays included were listed on the front cover:

HW felt that at last someone appreciated his work, and a strong relationship developed between these two men. Their extensive correspondence contains a great deal of literary and personal detail (it is lodged at Exeter University as part of the Henry Williamson Society archive, which is kept with HW's main archive there). See also Brocard Sewell's memoir, written after HW's death, 'Some Memories of H.W.'.

|

| Fr Brocard Sewell (left) and HW |

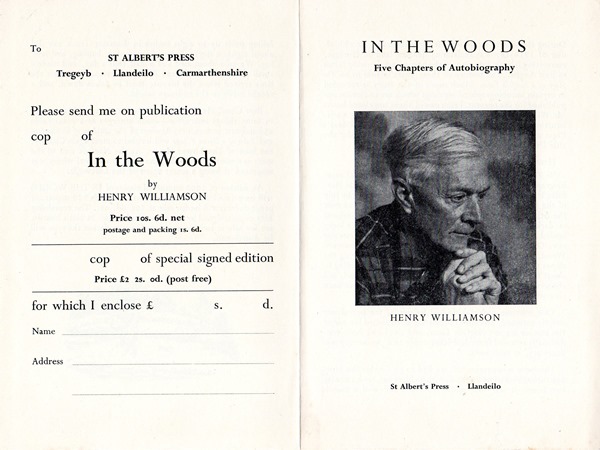

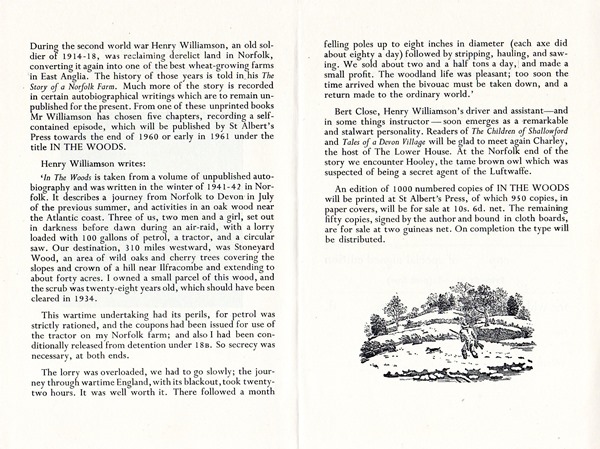

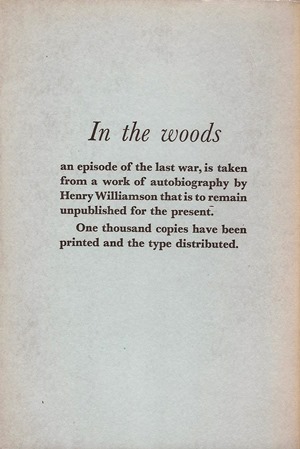

Shortly after the HW special issue, the magazine found itself in financial difficulty: costs of production outweighed financial return. Some additional capital was necessary, and in order to help raise this HW generously offered St Albert's Press a passage from a previously unpublished autobiographical manuscript, written as a sequel to The Story of A Norfolk Farm, entitled 'A Norfolk Farmer in War-time'. The passage relates the story of a visit to Devon to cut down trees in an area of woodland. A 4-page flyer advertised the publication:

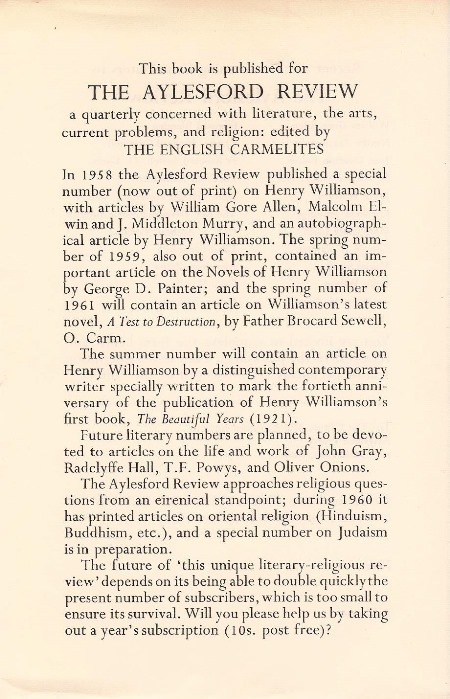

When In the Woods was published flyers were included in the paper-covered copies appealing for new subscribers to the magazine:

A further flyer inserted into the Aylesford Review Winter 1960–61 issue shows that there were other books and authors involved in this money-raising project.

Note the words 'Sustentation Fund': that is, 'to support indigent clergy' (indigent meaning poor).

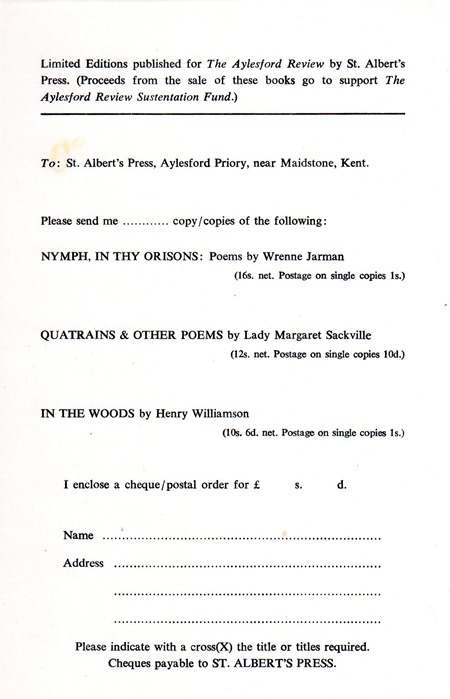

All the books on this list are reviewed within that issue:

Nymph in Thy Orisons (limited edition of 275 signed copies), reviewed by Edmund Blunden

Quatrains and Other Poems (limited edition of 275 signed copies), reviewed by 'R.N.G.A.'

In the Woods (limited edition of 1000 copies, 50 signed), reviewed by Anthony Gower (reproduced below).

Total sales of HW's volume should have raised around £600, so after printing costs a considerable amount would have been available for the Press – say £500. In addition, of course, there were the amounts raised by the other two volumes, so probably over £1000 in total (although they did not sell particularly well).

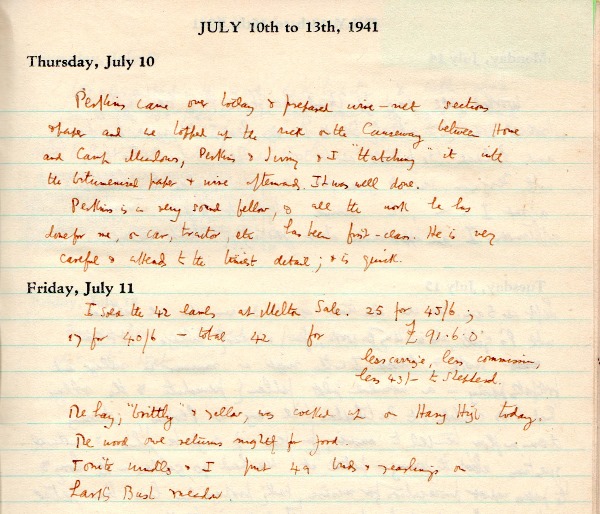

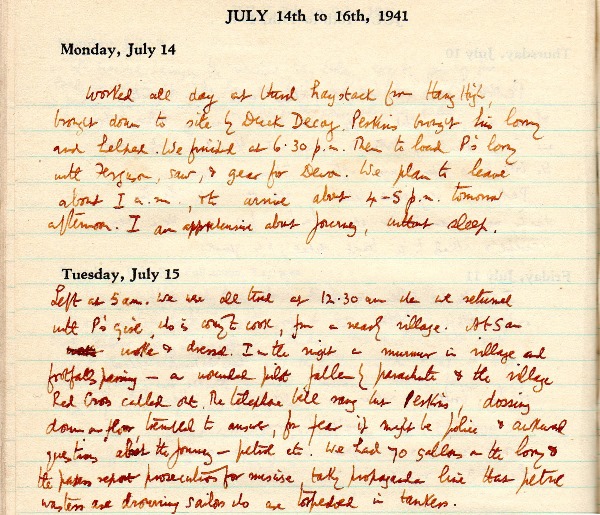

The In the Woods flyer, together with the reviews, gives the gist of the story very well. However a little further explanation and some background enhances the story. Outline details of this venture are recorded in HW's diary. The story actually opens before they leave for Devon, with the pre-journey cutting and carting of the hay crop, which is recorded in the diary from about 21 June 1941 to Monday, 14 July (before that it had been sugar-beet work). HW tells us how he had to sell his lambs at Melton before he could leave. That is recorded on Friday 11 July. That entry also includes mention of Hooly, the young tawny (wood) owl being brought up by the Williamson family.

The venture itself is recorded from 15 July to 13 August. HW was fitting this jaunt in between 'haysel' and harvest. (While he was away the harvest of oats was begun, and was continued on his return; also the wheat harvest, but a great deal of wet weather hindered the work and caused HW anxiety.)

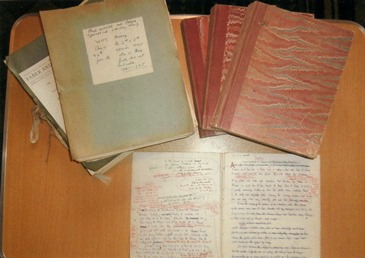

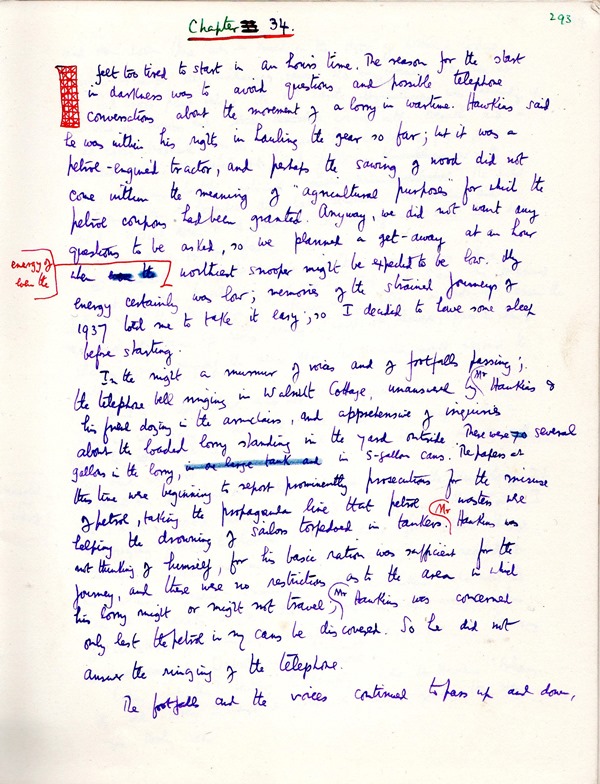

But also at that time (that is, from 1941 onwards) HW began to write what he intended to be a sequel to his Story of a Norfolk Farm, entitled 'A Norfolk Farmer in Wartime', which is written in manuscript, mainly in red ink (so quite difficult to read), in three quarto 1-inch thick board-covered notebooks. (There would have been a fourth volume also.) Like the original Story of a Norfolk Farm this is ostensibly autobiographical, although apart from the immediate family most names are already changed (and are recognisable as those used in the eventual Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight volumes). But indeed a certain amount of fictional embellishment is added even at that early stage – and certainly some real life elements are withheld, as will be seen.

After the Second World War was over HW had this manuscript typed up with a view to publication. For various reasons, however, this did not get published. One of the main ones was that by then HW was beginning the work on his major series, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, and was advised by his publishers to hold on to the material until its proper place in the time sequence; in due course it was indeed absorbed into the farm volumes A Solitary War and Lucifer Before Sunrise.

This Devon wood-cutting episode is found at the beginning of the third volume of HW's original 3-volume manuscript version, which opens as from his continuous page numbering on page 281, and encompasses pages 292–343.

Diary proper:

Diary entry in manuscript:

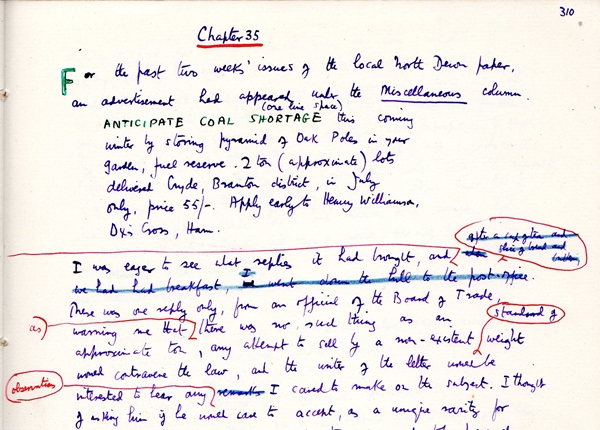

Monday June 23: Have made arrangements with Hawkins to go to Devon and cut the oaks in Stoneyard Wood after haysel . . . [Note the nom-de-plume here – see below.]

The relevant chapter in the manuscript describing their departure begins:

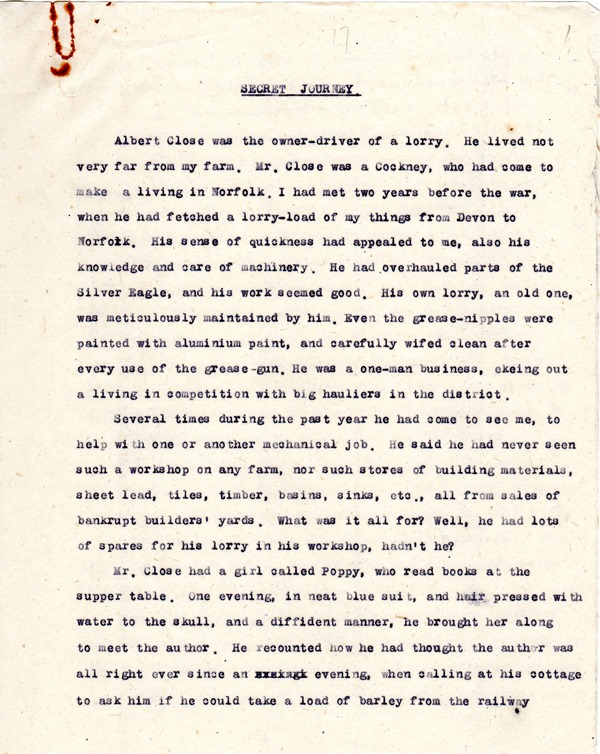

The typescript version opens with:

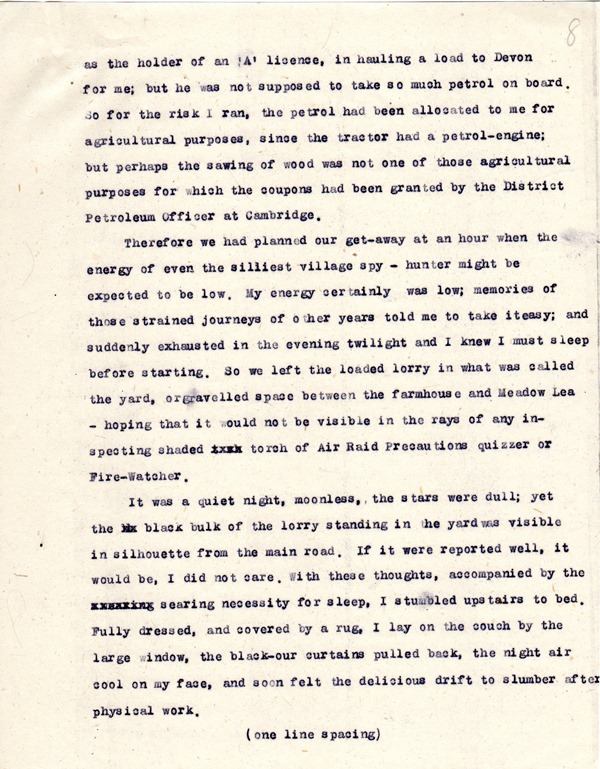

Page 8 covers their departure:

*************************

As the book opens we are introduced to the main character (apart from HW himself): Bert Close, full name 'Albert' (i.e. the 'Hawkins' in the above MS extract; his real name was in fact Eric Perkins, who is very faithfully portrayed), and his fictional girlfriend 'Poppy', in real life Kathleen Lack. There is a hint that Bert is actually married with children, because we read that HW has 'tea' with them – bread and dripping (semi-solidified beef or pork fat, a staple of the time and absolutely delicious!) – but that is never stated as such here. It is agreed that Poppy will accompany them and cook the meals and generally muck in with the work. As in due course they collect Poppy in great secrecy, this seems to bear out the 'already married' scenario, although they were having to be very circumspect anyway.

They sort out the problems concerning the war regulation petrol and travel restrictions. HW has an allowance of petrol for 'agricultural purposes', while Bert, as a haulier, has an 'A' licence which allows him to make journeys longer than the regulation limit of 30 miles. Even so they are on rather dodgy ground and if caught and questioned could find themselves in difficulties.

We read that during the night previous to their departure from Devon there was an 'alarum': a wounded German pilot had landed by parachute and the village Red Cross, of which HW's wife Loetitia was an active member, were called on to help. Perkins, 'dossing down on the floor' preparatory to a 5 a.m. start, was afraid to answer the 'telephone bell' in case it was the police making enquiries about their somewhat unorthodox trip.

HW adds in here a little vignette as they leave: the hour being '5 a.m., double summer-time, 3 a.m. Greenwich Mean Time'. This is a reference to the war-time change of hours to give maximum daylight for working. Indeed, there are many instances of social history in this short tale: small facts of what life was like during the war, all very subtly included: little details that add to the total picture. This particular vignette actually concerns Hooly 'our tame owl', which lands on Bert's cap and does 'a little mad dance of hunger on it. The owl was frantic for food, and Loetitia took it away to quieten it with pieces of rabbit.’ Hooly had been with them since a fledgling. We hear no more of him until the very end of the story – at which point more will be explained.

We read too of a selection of the various 'difficult' workers who had arrived on the Norfolk Farm, including registered Conscientious Objectors, whom HW discovered were not necessarily genuine, while they had little propensity for actual work (both on his own farm and that of John Middleton Murry's Community Farm at Thelnetham in Suffolk).

We learn quite a bit about the 'doings' of Bert Close and his business, for on this long and difficult journey down to Devon he tells his Chaucerian 'Haulier's Tale'. The journey itself has its own little hiccups and problems and is not without a certain amount of tetchiness!

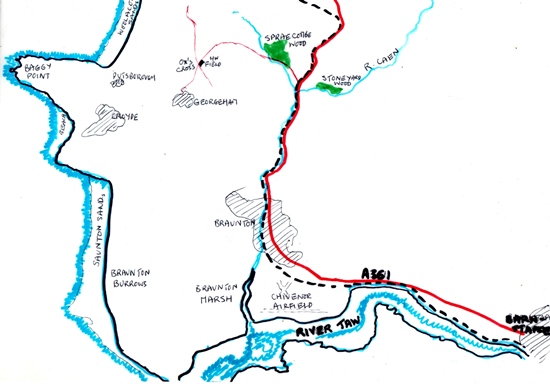

It is not until halfway through the book (p. 27) that they actually arrive at HW's Field at Ox's Cross above Georgeham at half-past two in the morning. As they near their destination:

It rained after Barnstaple . . . Figures appear and wave . . . They were airmen from the new station built on the marshes by the estuary . . .

The servicemen, returning from leave, hitch a lift, then at their destination jump off and vanish. This is the once private airfield at Chivenor, built on the edge of the Taw estuary (where Ann Welch, HW's original 'Barleybright', learned to fly – and where HW himself once had a lesson, to the total consternation of his instructor!), now commandeered by Coastal Command. On arrival at the Field HW makes his companions a hasty bed in the loft of the 'garage' up by the top gate (today a rather nice comfortable little chalet):

Bert Close had been driving for twenty-one and a half hours with ninety minutes stop for meals . . . Three hundred and thirty miles during twenty running hours: sixteen and a half miles per hour.

I slept where I lay (under a spruce tree), wrapped in the leather coat.

What we are not told in the book is that HW had a more personal reason for making the visit to Devon: Ann Thomas (his secretary and mistress since 1932, although at this time their relationship was somewhat strained) was currently actually living in HW's Writing Hut in the Field at Ox's Cross, and had a secretarial job in nearby Croyde with the Ministry. The reason HW slept in the hedge was because he did not want to disturb Ann, who was asleep in the Hut. However, his diary records that the next morning:

At 4.30 am I rose up stiff & cold & tottered into hut. She said I was silly to stay out, and my chivalry seemed wasted.

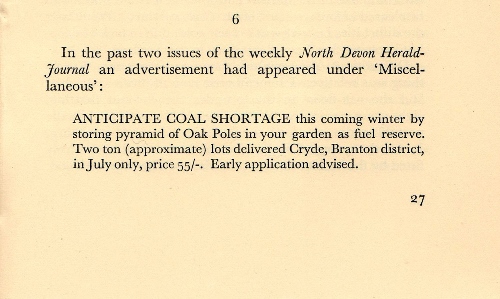

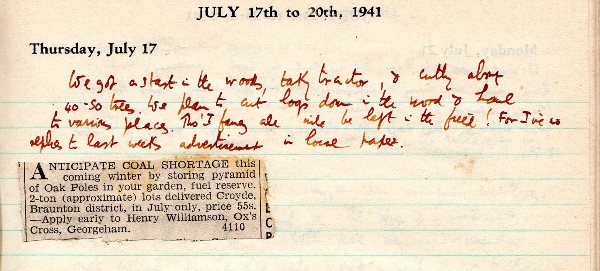

Before leaving Norfolk HW had placed an advertisement in the local paper, as he notes in the book:

More or less word for word, the actual advert is pasted into his diary, prefaced with the words:

For I've no replies to last weeks advertisement in local paper.

In the manuscript this appears as:

(Corrections here are a later addition – almost certainly when preparing In the Woods.)

The next morning they proceed to unload the lorry – which brings, of course, its own problems! They then set off to find Stoneyard Wood, and we are given quite precise instructions on how to find it, leaving ‘Windwhistle Cross' (such a lovely name) by the north gate. The road they follow goes past what is Spraecombe Wood and continues (crossing over the Braunton to Ifracombe A361 main road – not mentioned) to a hill near Halsinger, 'a small moor of heather and furze and bracken lying between the two greater moors of the Exe and the Dart watersheds'. Stoneyard Wood is marked on modern maps, and is about two miles due east of Ox's Cross.

This rough sketch shows the general area:

I have never found any details within HW's archive concerning the purchase or lease of this area of woodland. We are told:

The scrub-oak was usually thrown every twenty-one years and my acre and a quarter had been left to grow thirty-four years.

Thus the trees are leggy poles. Having arrived at the wood there is a further complication:

It took us the rest of the morning to find the area of scrub-oak which I had bought a decade before.

However, after a while a dog appears which HW recognises, and he meets up with the owner working nearby, who finds the marks they had blazed on to holly trees 'nearly obliterated by the rising sap of a dozen years'. That makes HW's purchase (of the actual wood, that is – not the land they grew on, so technically it was a lease) about 1930-ish.

Eventually, after several complications of clearing an entrance and manoeuvring the lorry to unload the machinery, all of which is related in the most interesting manner, they begin on the work. None of this is recorded in HW's diary where it is a prosaic:

We got a start in the wood, taking tractor, & cutting about 40-50 trees.

It is pretty hard work, cutting down the trees, sawing them up, and transporting the logs back to the Field. To begin with, he notes (in his diary) wood measured as '½ lorry load', but very quickly most days they were moving about 2 tons of wood. Interestingly he later notes in his diary:

11 tons now in woodshed. Estimate 1/8 acre in all has been cut, including 2 tons to Ann in December last. 40 year-old scrub oak. 18 tons from 1/8 acre = 144 tons per acre.

(2 tons to Ann the previous December rather raises a question in one's mind! However – the book is a story meant to entertain, and this detail is omitted from it!)

It rains a lot which makes things more difficult, and Bert gets neuralgia.

But it is not all work. We get a hint of Ann's presence on p. 38, at the very top of Section 8:

I had brought my bicycle on the lorry, and leaving Bert and Poppy the next day, a Sunday, to their own pleasures, I bicycled with a friend to the Chichester Arms at Morte . . . and there we drank two pints of cider before cycling back.

After lunch in the hut ('salad and cheese, with brown bread and honey') they go down to bathe:

and found the sands of the wide sandy bay set with thousands of posts against the landing of enemy aircraft.

And yes, HW's diary records that he and Ann did cycle to Mortehoe and drank cider at the Chichester Arms (which pub has featured in earlier books, notably On Foot in Devon), but returning in the rain 'for good lamb (roast) dinner in loft [i.e. over the garage building] cooked by Perkin's girl. Excellent cook.’

Another diary entry states:

Cut and brought back another two tons. It is lovely in the woods, the dappled sunlight, the fire for the teas billy-can at midday. Kathleen, P's friend, is an admirable girl – efficient, quiet, intelligent, most helpful . . . Ann also very sweet.

They all also went into 'Barum' (Barnstaple) at least twice to the cinema, and most evenings called in at the pub at the end of the day's work for a pint. The book records (but the diary does not) an incident in the village after they had been to the Higher House (the Rock Inn), where the landlord is Albert Jeffry (who has appeared in HW's earlier tales of village life). Remembering old grievances and new rumours, someone threatens to overturn Bert's lorry parked against the church wall. Bert, crafty Cockney that he is at heart, lurks in the shadows to come to HW's aid if necessary. However all is smoothed over.

They also go for a drink in the Lower House (the King's Arms) where Charley Ovey (again a well-known character from earlier books) still rules – and has his own teasing affection for ’Nry. I note that one reviewer says how nice it is to meet Charley again. Such characters are real friends to regular readers of HW's work.

At the beginning of August a letter from Loetitia tells HW that the oats on Spong Beck had been cut (for a map of the farm fields see the entry for The Story of A Norfolk Farm), while there is a mention of young Rikky, aged seven years (actually his sixth birthday had been on 1 August!), who had sent a head of wheat from Fox Covert. In brackets HW has later added further mention of 'little Richard Calvert Williamson, he was a good boy': the formality being because his son Richard had used his full name as author of his own book The Dawn is My Brother, published not long before! (A new illustrated edition of the book has been published by the HWS as an e-book, 2015.)

The end part of the wood-cutting interlude, both here in the book and in HW's diary rather peters out. The reason was that Ann's mother, Helen Thomas (Edward Thomas's widow), together with young Rosemary (HW and Ann's daughter), arrived at the Field, and so no doubt the last few days were hectic. The new arrivals took over the Hut with Ann, while HW slept in the potting shed in the vegetable garden, where his diary states he made himself a comfortable bed.

The book records that:

On the morning of our last day, a Sunday, I bicycled down the winding valley lane to the wood, to take a last look around. The area of our cutting . . . looked orderly and pleasing. I sat on a stump, in the stillness of the green forest. Through the tall and crooked trunks of the scrub oaks came the cries of small woodland birds. From high above the green canopies came the whistle of the rabbit hawk [buzzard] soaring over his eyrie. So silent otherwise was the wood that the noise of a blackbird scratching among the skeleton leaves, five yards from where I sat, was almost like a dog rooting there.

They had planned to leave at 8.30 the next morning (actually Tuesday, 12 August) but inevitably it was 10 o'clock by the time they were on the road. The book records breaking the journey at Oxford:

We called at a house in St. Aldate's where two old friends were living.

This was the home of his long-standing friends Petre and Jill Mais, then living at 91 St. Aldate's, Oxford. Walking around the next morning HW was surprised to see a shop window filled with 'immense bars of chocolate' (a very rare sight during the war) at five shillings a pound. We read that he bought four pounds of it, and on getting home gave some to his children. They were not impressed! It was actually cattle-cake, coloured to look like chocolate, and he already had four tons of that stacked in the barn – even the cows would not eat it. (This little tale is not recorded in his diary.)

The return home was marred by the fact that the telegram HW had sent from South Molton had not arrived, so Loetitia was not expecting them and had not got a meal ready: which caused irritation on both sides. We read only that Loetitia was tired and went to bed early. What we are not told in the book is that he had brought back someone with him (which wouldn't have helped the domestic arrangements!):

Mary de la Casas from Abbotsham to work on the farm.

There is no background information about how this arrangement came about; and again, although it worked well for a while, it was fairly short-lived and the lady departed: see AW’s biography Henry Williamson: Tarka and the Last Romantic (1995).

Very little of HW's wood was sold, about a quarter of its total. Other local people were also selling wood – the owner of Stoneyard Wood actually thanked HW for leaving the 'standards' (trees designated to grow to full height), which none of the 'others' had done. HW makes a little account for the venture: his diary records it thus:

Altogether we took 6 tons to Mrs. Service [someone Ann had met in the village] and a further £3 of wood in the village, selling £16 worth in all, and leaving approximately 20 tons in the field, value £45.

His total expenses for the trip, as he tells us in the book (wages for Bert & Poppy, fuel, etcetera), came to £36.

The book ends with news of Hooly, the tame tawny owl which had perched on Bert's cap as they left for Devon three week's previously, 'doing a little mad dance of hunger'. In reply to HW's question about Hooly, Loetitia tells him that she fears the owl has been shot by the soldiers as one had attacked the Searchlight Camp men and had met its end.

'Perhaps they thought it was a German spy-owl,’ I said.

He reminds himself (scratching a permanent sore place in his mind) that the villagers thought his Alvis Silver Eagle – that most English of cars! – was of German origin and of course that he was a spy.

However, as he goes out to look round the farm buildings in the dusk he sees an owl perched on a willow branch near the duck-pond. It is indeed Hooly, and the owl allows him to stroke his head.

Hooly looked very handsome in his (or her) new browns and blacks and whites [i.e. the owlet now has its adult feathers], and the eyes had that full authentic keenness of perfect natural form . . . then, without a cry, Hooly flew into the twilight, . . . and so into the wild world. I knew that he would never come back, and I was glad that he had not been shot.

Perhaps we would catch a glimpse of Hooly again . . . [some day] . . .

Of course, what HW is really doing here is using his writing craft to give this story a superb ending.

The Williamson family did indeed have a young tawny owl as a pet. The story first appeared in the Eastern Daily Press, in two parts, on 5 July 1943 and 12 July 1943, and is reprinted in Green Fields and Pavements: A Norfolk Farmer in Wartime, ed. John Gregory (HWS, 1995; e-book 2013). It was also, with some small differences, published in Strand Magazine, December 1944; while it later appears as chapter four, 'Hooly', in Lucifer Before Sunrise, where it is adapted into the Chronicle format.

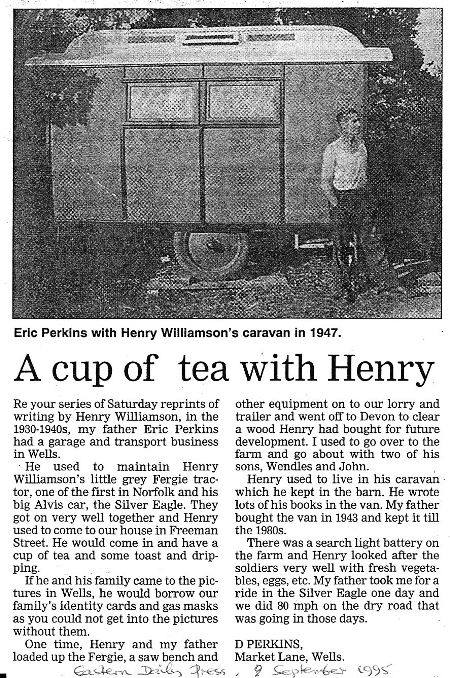

Many years later, one of Eric Perkins' children sent this letter and photograph to the Eastern Daily Press, which it printed on 8 September 1995; it adds just a little more to the story, and forms an appropriate coda:

*************************

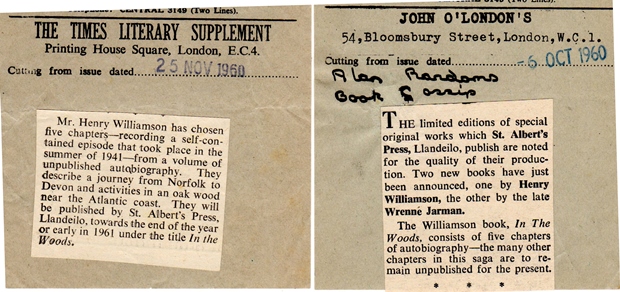

Pre-publication information:

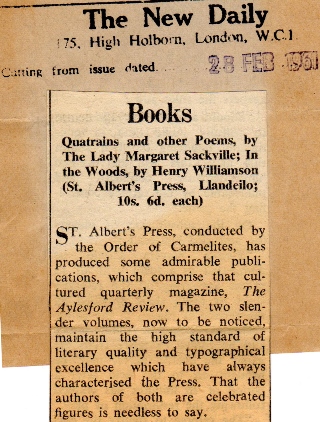

The New Daily ('C.R.C.'), 28 February 1961:

A review of Lady Sackville's poems follows:

. . . Lady Margaret has enriched our poetry with works of genuine beauty in many forms . . .

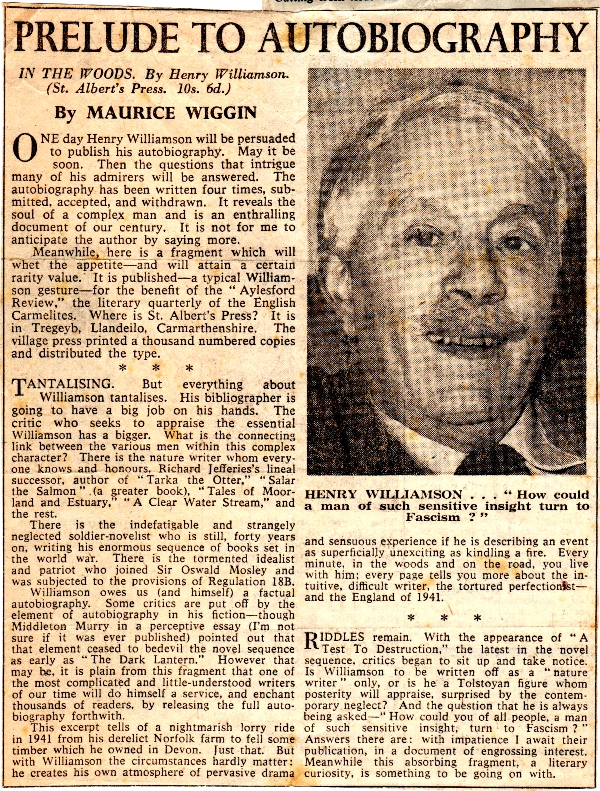

The Sunday Times (Maurice Wiggin), 5 March 1961:

Eastern Daily Press ('M.P.'), 11 March 1961:

Eastern Daily Press, 20 April 1961: Letter from HW

HW's claim here of the amount of material involved is a little exaggerated. It was not until he incorporated his original material into the farm volumes of the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight (vols 13 and 14) that the piles of typescript really mounted up.

John O'London's Weekly ('Compiled by John O'London's staff'), 16 March 1961 (The comments are, of course, in HW's hand):

This unattached and unattributed striking photograph also came from this issue:

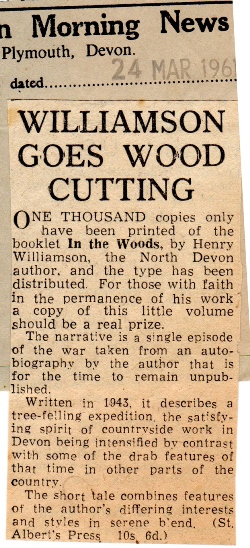

Western Morning News, 24 March 1964 (Rather short and slightly grudging, considering it was a 'West Country' subject):

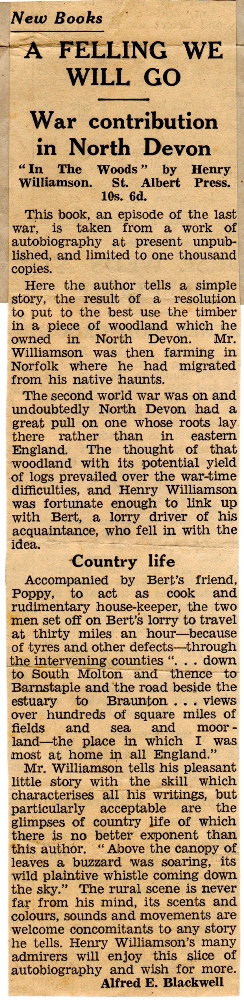

North Devon Journal and Herald (Alfred Blackwell), 6 April 1961:

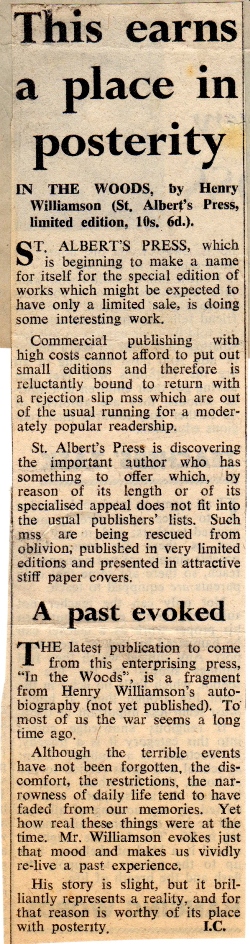

Catholic Herald ('I.C.'), 14 April 1961:

The Listener (C. Henry Warren), 8 June 1961:

('Antilogy' means 'contradiction in terms')

The Daily Telegraph (Sean Day-Lewis), 14 June 1961:

Three books were reviewed:

The reviewer is rather critical of the first two (especially the second) but between them they get 7 column inches; In The Woods gets 1¼-inches.

The Aylesford Review (Anthony Gower), Vol. IV, No. 1, Winter 1960–61, p. 34-5:

Also in this issue was the following advertisement for the book (p. 30):

*************************

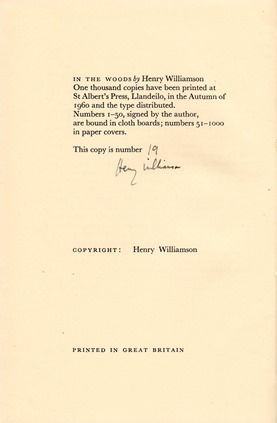

The first 50 copies were bound in quarter green cloth with cream boards, with a signed sheet at the back:

|

|

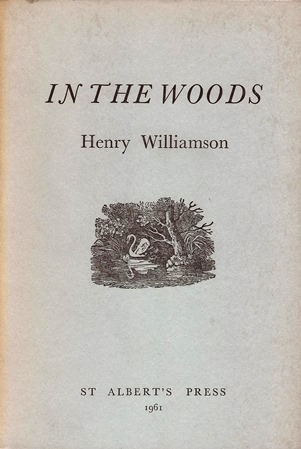

The remaining 950 copies were bound in sky blue card, with a card wrapper bearing a woodcut by Thomas Bewick:

|

|

*************************

Go to Appendices

*************************