A FOX UNDER MY CLOAK

(Vol. 5, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight)

|

|

| First edition, Macdonald, 1955 | |

First published Macdonald, 11 November 1955 (15/- net)

Macdonald, second impression, 1962 (with some small corrections)

Panther, paperback (slightly revised), August 1963

Chivers Press (New Portway series) by request of the Library Association, 1983 (reprint of the first edition, and so contains its errors, e.g. on first page (p. 11) the rifles are ‘Lee-Metfords’ instead of the correct Lee-Enfields)

Macdonald, reprint of first edition (again containing its errors), 1985 (£12.95)

Sutton Publishing, paperback, 1996

Currently available at Faber Finds

The book has an interesting author’s note and dedication:

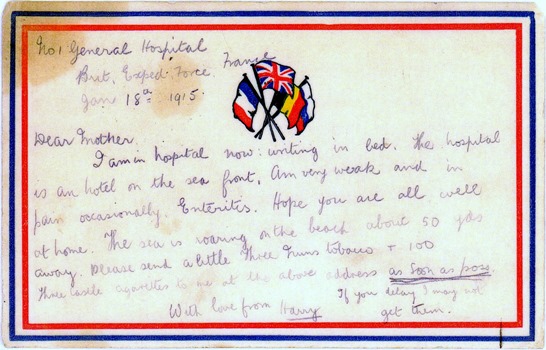

A Fox Under My Cloak opens with Phillip Maddison and his fellow London Highlanders still out ‘at rest’ (a euphemism for further training) at St Omer, where in the first week of December 1914 all the troops are inspected by King George V and the Prince of Wales. While playing football a message comes ordering them back into the Front Line where the London Highlanders are part of the (now famous) Christmas Truce, which makes a deep and lasting impression on Phillip. The conditions are appalling, and in January Phillip is sent back to England suffering from severe gastroenteritis and trench feet. While on convalescent leave he applies for a commission into the Gaultshire Regiment (the ‘Mediators’) and soon commences training, a difficult period for the still uncouth youth, and in a moment of despair he requests to return to the Front: changing his mind he later applies for transfer to the ‘Diehards’ (the Middlesex Regiment), but unbeknown to him the former application has already been forwarded.

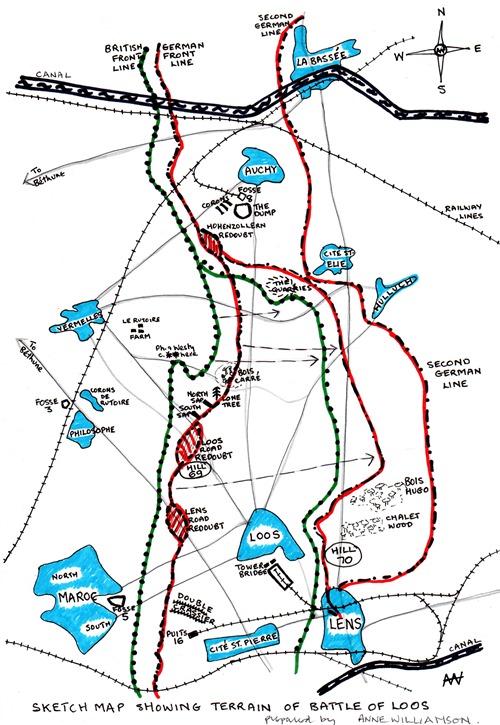

So, as a raw second lieutenant, Phillip returns to France, immediately volunteering to train as a gas officer (which he sees as a cushy alternative to the Front Line). As such, in September 1915 he is posted to the trenches east of the town of Loos to prepare for the forthcoming ‘Battle of Loos’. Here he meets Captain ‘Spectre’ West, a major character of these war volumes. Scenes of the battle are described in detail. But Phillip’s earlier application to be transferred to ‘the Diehards’ comes through and as this volume ends he has returned to England.

*************************

It has already been made clear that there was considerable overlap between the various stages involved in the production of each volume of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight. HW recorded that on 28 December 1953 he sent off the last part of How Dear Is Life to his typist: the entry for Friday 1 January 1954, just three days later, states: ‘Am on with A Fox Under My Cloak.’

Saturday 2 January 1954: Writing. No time for diary entries. Too weary.

And the diary is blank until Sunday 7 March: ‘Am still writing Fox Under Cloak.’

The entry for 14 April reveals that How Dear Is Life had finally been sent off to Macdonald’s:

Meanwhile I have done the best part of No. 5 (A Fox under My cloak) & have stopped for a rest. What remains is a short (12,000 – 15,000 words) description of Loos, 1915, wherein Phillip is a spectator.

Mainly this ‘rest’ involved ‘digging the garden . . . field to be plowed & sown, garage to be repaired, new hut built [the Studio], the Aston-Martin still not in order . . . scores of letters to be answered . . .’

He was reading J.H. Morgan’s Assize of Arms: ‘for my work. My aim & idea is to learn and to try & get at the truth.’

On 26 April while on a visit to his first wife Loetitia at Bungay (Suffolk) he notes the forthcoming trip planned for the battlefields with Eric Watkins (as already related in the page for How Dear Is Life) in order to: ‘Visit scenes of Dear Life, & also the Loos country.’

The two men left on Friday 7 May (but is wrongly entered under 14 May and following):

Went to Northern France with Eric Watkins on staff of News Chronicle. Arrived Bethune about 4 p.m. Walked part of the way to Loos, then by bus. Stayed night at Loos. The place is still very sad, as though unvisited by the spirit of forgiveness. Loos still looks rough.

Great pyramids arise out of the cornfields, some 500 ft high, from the mines under the chalk. . . .

8 May: Weather fine & hot. We looked at the Double Crassier, weed-grown. Chalk in fields showed where trenches and dugouts were. . . . Then up to Hill 70, the German H.Q. in Sept. 1915, with its views over the rolling fields below. [Significant landmarks in the Battle of Loos.] Thence down to Lens, & up to Vimy Ridge: blisters bad by now, great heat, packs heavy: I grew irritable & critical . . . making for Arras . . . got bus to Lille.

Sunday 9 May: Went by bus to Armentieres. Had coffee there & rolls & butter. Walked to Ploegsteert. Blisters bad. The old (or new) wood pleasant, quiet, cuckoo-haunted (& nightingales) & the graves in the middle of it. We were chased by a woman, who told us we trespassed: the wood belonged to General Leclerc. Walked past the 1914 Christmas Truce site (where was it exactly?) . . . [and so to Messines & the Scottish Memorial – which area came into HDIL]

In mid-June HW attended a West Country Writers Association meeting at Weymouth, where he met Ruth Tomalin, newly acclaimed author of a biography of W. H. Hudson (one of HW’s chief inspirations after Richard Jefferies) to whom he felt greatly attracted. But after his return from France there is actually a gap in the diary until Sunday 11 July which records: ‘Have petered out over Fox Under Cloak.’

Wednesday 29 September: Have been writing intensively for past month on the Loos Battle in my new novel. It has come with difficulty.

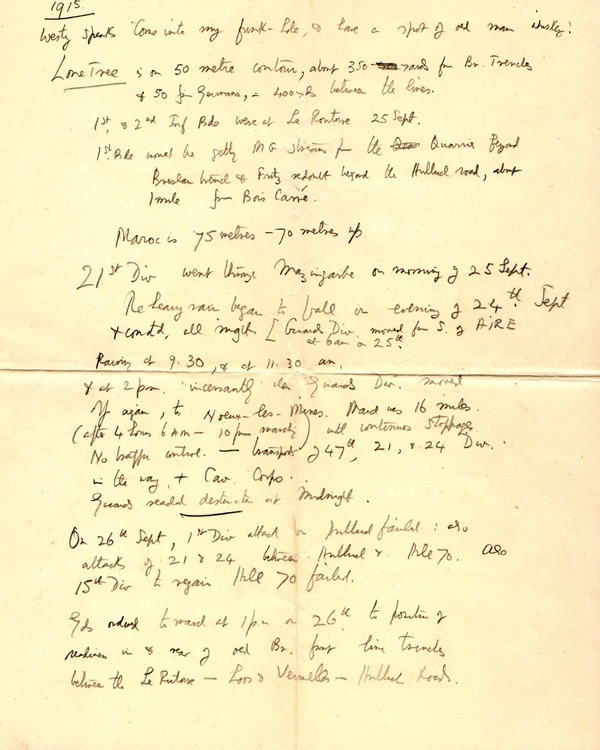

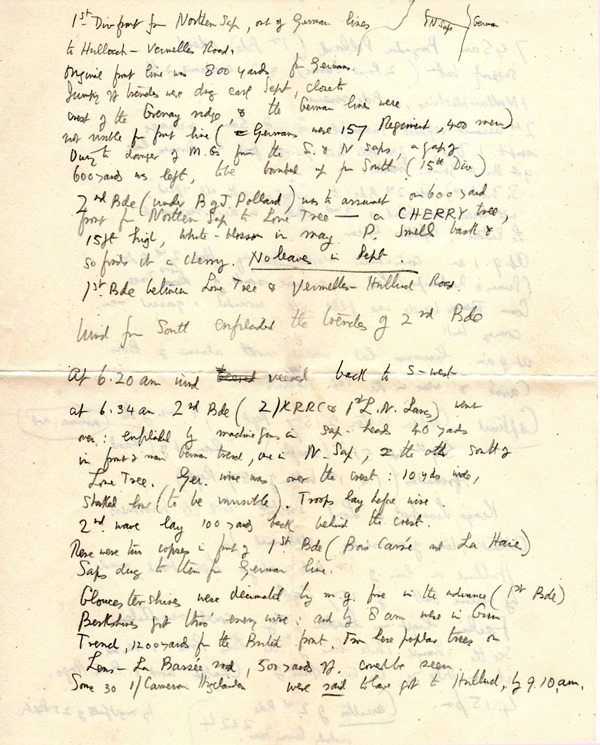

The scans below of just a few pages of HW's detailed notes and much revised and corrected manuscript give an illustration of the task he had set himself:

In early October he was in London and seeing Ruth Tomalin daily, but she tended to keep him at arm’s length. On Monday 4 October there is a significant entry: ‘Worked in Imperial War Museum.’ The following day: ‘ditto’; and on 6 October: ‘Bought the volumes of Official History of the Great War at Joseph’s, Charing Cross Road for £5/10/-.’ (This multi-volume detailed analysis and record was compiled from the Official Records of each of the myriads of military operations kept throughout the war, and is an invaluable record of those events.)

The diary then records for several pages the ongoing and now open problem concerning Christine’s infidelity with Alan Bowley, the artist from Appledore with whom she was having an affaire. There were also huge problems with the building of the new studio – the builder not using the special water-tight aquacrete cement, and lying about it. All this severely disrupted his writing.

On 6 January 1955 HW met Eric Harvey (his current publisher) at Macdonald’s about the contract for Fox Under My Cloak: £300 on signing the contract, £300 on delivery of the manuscript (typescript). The following morning he recorded:

At 1 am sitting up in bed writing . . . notes about the beginning – the difficult beginning – of FOX UNDER MY CLOAK.

9 January: To resume Fox. Sequence remains as at present. Add P. in wood, over brazier which is given him, setting up Helena’s photograph in the frost in the [slanting?] of the Very light, & feeling exhilaration & proud that she was looking at him.

11 January: Re-writing the early Loos part. The character of ‘Westy’ was altered some time ago: so his talk has to be brought into line with the scholarship boy who got to Oxford University in 1911, taught two terms in a prep school, joined the militia battalion of the Gaultshires; & at Loos was Capt. West, M.C.

13 January: Snow came at 2 am & soon the field & drive were covered thick . . . I wrote all day, & glowed with satisfaction at the results: the revision of the 1914 frost-wood scenes, & Xmas day . . . (I wrote in the hut, by a big oak fire).

There is no indication as to when A Fox Under My Cloak was sent off to the publisher – but it would have been before he left for Ireland for a long holiday at the end of May, having bought an Austin Countryman in late April, obviously with the idea of a family camping holiday in mind. This turned out to be rather disastrous, as it rained and things inevitably went wrong. They ended up staying with his great friend Sir John Heygate, now well entrenched in the Irish estate he had inherited from his uncle – but that also had its problems, as he suspected John of making a pass at Christine. They returned on 20 July.

The diary is then blank again until 8 November when he recorded:

Had a nice letter from General Sir Hubert Gough thanking me for a copy of A Fox Under My Cloak. [This will be explained in due course.]

Then three days later, on 11 November, the entry states: ‘A Fox Under My Cloak published today.’ That same day he inscribed and sent a copy to Douglas Bell:

Bell sent a letter of thanks, which HW pasted into his own copy of the book:

*************************

It is interesting that HW used his title A Fox Under My Cloak right from the very start. There is no indication about his reasons for this whatsoever, but it is derived from two sources. One is enigmatic and obscure, deriving from Plutarch’s Parallel Lives, the first-century book in which Lycurgus, the law maker of Sparta, relates the life and training of Spartan boys, disciplined from the age of seven through sport and study to obey commands, endure hardships, and conquer in battle. At the age of twelve they were placed in the care of a trusted senior who acted as father, tutor, governor and usually also lover. Their diet was deliberately meagre in the extreme to make them cunning and bold and to make them grow tall. They were encouraged (expected) to steal (to enhance their skills) but if found out were flogged mercilessly.

This, of course, was an ideal training for men who were to be warriors, brave and successful in battle in such ancient times. It is obvious that HW knew this tale from the Classics from his schooldays. (Apart from school lessons, his Aunt Mary Leopoldina had given him a Dictionary of the Classics in 1912.) Transfer the Spartan ethos from ancient times to the twentieth century and replace the concept of Spartan youth with that of First World War soldier and one sees what HW was driving at. Further, Plutarch’s tale continues with an example. Spartan youth took this ‘stealing’ so seriously that one boy, having stolen a young fox, concealed it under his clothes (cloak) but when challenged he let the animal tear out his bowels with its teeth and claws, dying as a result, rather than have his theft detected.

Thus HW’s title here would appear to epitomise bravery under extreme conditions. But, within HW’s novel, towards the end, is a phrase which counters that. HW is writing about Field Marshal Sir John French, commanding the army at this point of the war, who due to extreme stubbornness, did not send up reserve troops to the Front Line and so the impetus of the attack was not followed through and it failed. HW states: ‘Anxiety gnawed him [i.e. French], a fox under his cloak.’(Ch. 23, ‘Historical Perspective’, p. 338, 1955 ed.)

So our grasp of the meaning of this title is rather turned upside down. Further, remembering that the chief character of this tale is not Sir John French but Phillip, and having given us this clear clue that the title does not necessarily concern ‘bravery under extreme conditions’ but something less certain – ‘anxiety’ – we need to apply that meaning to Phillip and the situation he is in: the fox under Phillip’s cloak is also ‘anxiety’ – but in its extreme form of ‘fear’.

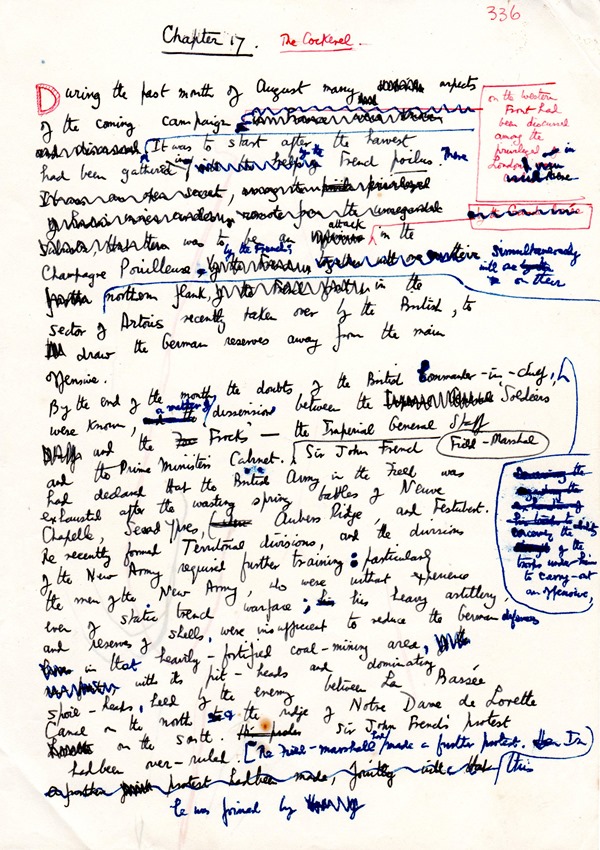

The more direct and obvious source of this title is from the red fox emblem taken by the Fifth Army under General Sir Hubert Gough (and worn on the shoulders of tunics of those in the Fifth Army and so under their ‘cloaks’, i.e. Army trench coats), although the Fifth Army did not come officially into being until mid-1916. Gough was, however, out in France from the very beginning of the war and was involved in the retreat from Mons, the First Battle of Ypres, and was in command of 1 Corps at the Battle of Loos, and was in charge of the ‘Reserve’ army which was later officially designated the ‘Fifth’. Gough was unfortunately maligned for poor leadership (basically a government scapegoat) and (against Field Marshal Haig’s wishes) duly replaced by Rawlinson: although his extraordinary service was later recognised and his work vindicated. HW may not have realised, or more likely he deliberately fudged, the fact that the fox emblem was post-Loos.

The two elements come together to make a powerfully allusive title.

So, coming back to the fact that HW had sent Gough a copy of Fox Under My Cloak when it was published: HW served in the Fifth Army when he returned to the Front Line in 1917, and so had literally worn the ‘Red Fox’ under his cloak, and after the war he was a member of the Fifth Army Old Comrades Association. Gough wrote a letter thanking HW for the book and in return sent a copy of his own memoirs, Soldiering On (1954). There are two or three letters and a Christmas card from him in HW’s archive.

Gough died in March 1963, aged 92, and HW attended his Memorial Service in Westminster Abbey on 4 April 1963. The Red Fox Magazine (the organ of the Fifth Army Old Comrades Association) reprinted that September the very moving obituaries from The Times and the Daily Telegraph along with regimental tributes.

|

|

| HW's Fifth Army memorabilia, including his Old Comrades Association badge, below | |

*************************

A Fox Under My Cloak is divided into three parts, ‘Leytonstone Louts’, 'Temporary Gentleman' and 'The Battle of Loos'.

Part One, ‘Leytonstone Louts’

These lads have been a thread in the story of the war from the beginning: occupying the next tent at the Crowhurst Camp, insulted by Phillip, and occasionally threatening to fight him, although this has up to now been thwarted.

But the story opens with the inspection of the troops by King George V and the Prince of Wales at St Omer (where the London Highlanders are currently ‘at rest’), which took place in the first week of December 1914. HW slips in one of his ‘father/son’ points here: the Crown Prince is ‘a small white-faced boy in the shadow of Father’ (as HW felt himself to be).

Soon after this the battalion’s dream of Christmas in billets is shattered by the order ‘to move at once’. While packing up a quarrel flares up between Phillip and the two remaining ‘Leytonstone louts’, Church and Collins, and they arrange to fight when convenient.

The men are marched off towards Ypres, but then turn south until they come to a wood. Although not actually named, the ‘clues’ given reveal it to be the ‘Grand Bois’, just north-west of Wytschaete. (Phillip later returns to the village of Vierstraat where they are billeted – and he visits the ‘Red Château’ which lies on its south-west edge, from where he can see the ‘Hospice’ which is on the outskirts of Wytschaete.) The German Front line is only yards away.

They dig in; the weather worsens. Phillip is suffering from severe diarrhoea and frozen wet feet (the dreaded trench feet) and so is in constant pain from both complaints. A small attack takes place on 19 December, which fails. Then Phillip and Church quarrel again and they clamber out of their trench into No Man’s Land and finally have their fight – Church inevitably wins! They shake hands and the animosity has evaporated. The story of this fight gets back to England, highly exaggerated – brave soldiers fight fearlessly within sight of German soldiers in No Man’s Land – to Phillip’s confusion (although he plays on it later when returns to England!). But then a ‘wind-up’ starts and we have one of HW’s grand panoramic, epigrammatic descriptions:

As before a wind, fire swept with driven bright yellow-red stabs of thorn-flame up the line. . . . bullets in flights, hissing, clacking, or whining, crossed the line of the hosts held in the continuous graves of the living above the hosts of the unburied dead slowly being absorbed into the earth. The wind of fear, the mighty wind of the battlefield of Western Europe, from the Baltic Sea to the great barrier of the Alps, a fire travelling faster than any wind, . . . [throughout the length of the Front Line, place names all mentioned] to die out, expended [at the Alps, where rose] the constellation of Orion, shaking gem-like above all human hope.

In common with other troops at the front, both officers and men, HW received a brass Christmas box from Princess Mary, containing cigarettes and tobacco (for non-smokers the box contained a bullet pencil and sweets); this he kept for the rest of his life, including the (empty) cigarette cartons and tobacco pouch:

Sergeant Douglas (Douglas Bell, ex-Colfe’s and later friend – see A Soldier’s Diary of the Great War) selects Phillip (as punishment for the fight) to go out with the next listening party. So on Christmas Eve Phillip’s platoon are detailed to put up to fences across the open area to make cover to take men to the firing trench, the infamous Diehard T-Trench (the Diehards were the Middlesex Regiment). (Note – this occurs in the Grand Bois in the novel; HW was actually in Plugstreet Wood over this Christmas Period where it was the Hampshire T-Trench that was involved.) The men go out in great trepidation, warned to maintain absolute silence for the dangerous task, but as nothing untoward happens, they gradually relax. Suddenly a light is seen on the parapet of the German lines, then cheering breaks out: ‘Hoch, Hoch, Hoch!’ It is midnight by German time – and so Christmas Day. A German baritone sings ‘Heilige Nacht’ – and there is no shooting.

The next morning Phillip, finding a bicycle, goes off on his own to the village, visiting the Red Château en route – a grim place with dead swollen bodies lying about. On his return to his line he finds a crowd of soldiers, English and German, playing football together. Hearing the London Rifles are at Plugstreet he decides to go and look for his cousin Willie. He cycles daringly behind the German Lines without challenge and ends up at St Yves (on the north-east corner of Plugstreet Wood – a distance of about 5 miles from his base). Eventually he meets up with Willie at the Le Gheer crossroads (on the south-east corner of the wood).

This is in fact where HW himself would have been during this amazing Christmas Truce. Indeed, Willie Maddison is as much HW as Phillip is. Willie is full of the fact that the Germans believe they are fighting for God, Freedom, and their country exactly as did the English. These are the thoughts that HW had – and which so marked him for the rest of his life.

HW wrote a letter home describing the Christmas Truce which his father arranged to be printed in the newspaper (see also the page for the Christmas Truce, where it is reproduced in full).

Apart from the content itself one has to admire the structural device with which HW solves the problem here, overcoming the fact that Phillip was NOT in Plugstreet Wood where his own experience had taken place, although one does have to suspend disbelief with regard to the amazing cycle ride behind enemy lines!

Phillip returns by road (this is how one can place his actual base so exactly) and hitches a lucky lift in an ASC lorry back to the London Highlanders’ line in the Grand Bois. The truce, which has become so famous a feature of the First World War, ends on New Year’s Day.

The description of life in Diehard Trench in the Grand Bois in early January 1915 is pretty grim. Phillip has constant debilitating squitters and the trench is three feet in water. Their attempts to pump it out are in vain. Phillip hacks two feet off the bottom of his great coat to relieve the weight of mud and water (as did HW). Church is killed by a sniper.

Finally they are to be relieved. Phillip stays behind for yet another painful evacuation of his bowels and falls asleep – only to hear Tommy Atkins telling him to move (Tommy Atkins was a real person). When he rejoins his platoon we are told that Tommy Atkins had actually died that morning.

Back in their billets (in Vierstraat village) Phillip is put on light duty, and so stays behind when the men return to the trenches. He is then sent to the Field Hospital at Kemmel, where he is diagnosed with severe enteritis and trench feet, and, to his great relief, sent back to England. (HW suggests that Phillip ‘swung the lead’ – thus implying that he himself had done so; but that would not in fact have been possible. In fact HW was quite ill when he returned – his sister Kathy said they hardly recognised him when he appeared.)

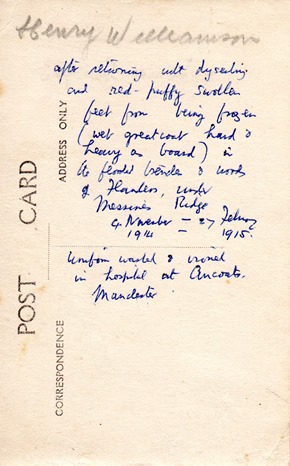

So HW, suffering from those same quite severe debilities, and having written similar letters home, returned to England on 26 January 1915, and sent first to Manchester Hospital and then Alderley Edge Convalescent Home. (Full details can be found in AW, Henry Williamson and the First World War.)

|

|

On recovery, the Medical Board gives Phillip three weeks leave (as was HW). His homecoming is shown to be very strained, as it was in real life.

Once home he meets up with his old pals from civilian life, goes drinking, and generally being difficult. His parents do not understand such behaviour and make no allowances for what he has been through – indeed there is no understanding whatsoever of what life at the Front has been like.

Part Two, ‘Temporary Gentleman’

Most of the chapters in this part are variations on the theme ‘Life is a Spree’! Phillip is spreading his wings – or trying to, for usually he falls flat on his face.

One of his pals, Tom Cundall (this is Victor Yeates, Old Colfeian schoolfriend, who was to write later, with HW’s help, the now classic Winged Victory, the fictionalised story of his life in the Royal Flying Corps) advises Phillip to apply for a commission. This he duly does. While waiting for this to be ratified he visits his cousin Polly at the family home at Beau Brickhill (the fictional Gaultshire – actually Bedfordshire), but although she comes into his bed at night he is unable to respond. He is still enamoured of Helena Rolls, and tries to give her a brooch of his regiment’s badge, which she refuses. (HW did indeed give such a brooch to Doris Nicholson at this time: see Anne Williamson, ‘Helena Rolls’ Brooch’, HWSJ 33, 1997, pp.48-9.)

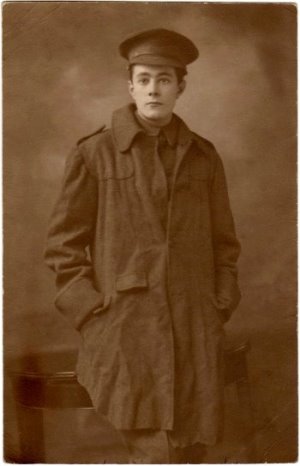

Phillip is ordered to report to Sevenoaks for the introductory Officer’s Course: he takes minimum notes and finds it all rather boring and out of touch with the reality of life at the Front, and says so, making himself unpopular. He buys a motorcycle and so now is able to rush around easily: he paints the name ‘Helena’ on its side.

This all follows HW’s own experience and on 1 May 1915 he bought a Norton motorcycle, LP 1656, on which he painted the name ‘Doris’, the real name of the fictional ‘Helena’.

|

|

The newly commissioned 'temporary gentleman': HW in 1915 |

|

|

Terence Tetley and HW on his pride and joy – 3½ h.p. 1914 Norton, LP 1656 |

As the course ends, Phillip is told to report to the ‘Cantuvellaunian’ Regiment at Heathmarket (HW was sent to the Cambridgeshire Regiment at Newmarket, Suffolk) for duty and further training. The officers are quartered at Godolphin House (its real name), while the battalion's senior officers are honorary members of the 'Pigskin Club' (the Jockey Club). Basically, Phillip, gauche and socially out of his depth, makes himself very unpopular at Heathmarket. The regiment is of the old school and make it clear they do not want a jumped-up outsider in their midst, particularly one with a noisy motorcycle (in the town where precious race-horses come first in consideration), and who shoots his mouth off about what life is really like at the Front, and so how useless the current training is. The chief proponent of his misery is the arrogant Baldersby – ‘Baldersby, of Baldersby Towers, Baldersby, Berkshire’.

Phillip gets involved with a flashy garage owner and also with a married woman called ‘Fairy’, and this thread weaves through the various points of training (during which, for instance, he learns to ride a horse after a fashion). But the main theme is the bullying that Phillip has to endure and the somewhat stupid things he does which manage to antagonise everybody else. It is at times hilarious and at others desperately difficult: quite what would once have been called ‘a rollicking good tale’! After he sets fire to the colonel’s newspaper in the reading room he is summoned to a ‘subaltern’s court’, which results in his being soaked with pails of water in bed and all his furniture being thrown out of his upstairs window, culminating with being beaten with wet knotted towels. These events all actually happened to HW. But once over, they all shake hands and have a whiskey! However the totally miserable Phillip has decided to ask for transfer back to the Front, although he never sends it off – but the mess sergeant finds it and forwards on the request.

Baldersby is to get married and departs in a drunken cloud of glory. But a sotto voce aside tells us that Phillip never saw him again: the first time Baldersby was sent to the Front he was killed immediately. (Again, this incident is based on real life; his real name was Formby, of Formby Hall, Formby, Lancashire.)

|

|

Godolphin House, Newmarket, where the 'Cantuvellaunians' were quartered. Phillip/HW's room was one of the top row of windows. (photo courtesy of G. Shingler, 2014) |

The regiment is sent to Southend for a trench and musketry course, where Phillip meets a flamboyant (but fraudulent) Adjutant of the ‘Navvies’ Battalion (of the Middlesex Regiment). He decides to get into that and asks for a transfer.

On their return to Heathmarket, a single moment of sex with the cloying ‘Fairy’ makes Phillip panic, immediately believing that he must have syphilis. But as he returns to barracks late that night he learns that his transfer has come through – not to the ‘Diehards’ as he presumes – but his original (forgotten!) request to return to the Front. He is to leave the next morning.

Part Three, ‘The Battle of Loos’

This part carries the quotation:

‘A Real British Victory at Last’ (Headline in the Daily Trident, 27 September 1915)

[The Trident , the paper read by Richard Maddison, was actually the Daily Mail]

This was typical of the sort of headline that did appear in newspapers after the appalling chaos of the Battle of Loos, with its massive loss of life, with which the British public were bamboozled into thinking that all was well with the war and it would all be over soon, with British victory assured. Although some of the point of such an attitude was to keep up morale at ‘home’, we know now how false that sort of headline and news actually was. It was one of the things HW strove to correct throughout his life: part of his seeking after the Truth syndrome. Its use here is ironic: we know the headline is a lie.

Phillip is given twenty-four hours embarkation leave and returns home where, while he is plucking a chicken for Mrs Rolls, he discovers his cousin Bertie (Hubert Cakebread) is writing to his beloved Helena, who is obviously enamoured. Phillip is distraught, but his mother suggests a picnic at their old childhood haunt of Reynard’s Common, which calms him into acceptance of the situation.

On reporting, he is ordered to escort a draft out to the Front. Once there he sees a notice asking for officers to volunteer for training as gas officers. Thinking this to be a cushy alternative to the Front Line, Phillip volunteers.

After training he is sent into the trenches to learn the layout and prepare for the coming attack, and here he meets the capable and clever, but bitter and hard-drinking Captain Harold ‘Spectre’ West (1st Battalion Gaultshires), who is to play an important part in the ensuing war volumes.

[An investigation into the background of ‘Spectre’ West can be found in Anne Williamson, ‘Some thoughts on ‘Spectre’ West and other elusive characters’, HWSJ 34, September 1998, pp. 86-94. We know now that Spectre has characteristics from various ‘real’ people, but did not actually exist in real life (as did most of HW’s characters). He appears to be in fact an ‘alter ego’ for HW – possibly the man HW would have liked to have been.]

The men are billeted at Mazingarbe, and they are holding the line half a mile from the famous ‘Lone Tree’, with the Germans entrenched behind it. (‘Lone Tree’ was a cherry tree which had bloomed the previous May, but now was a bare broken stump about fifteen feet high and a well-known landmark.) The British Support HQ was at Le Rutoire Farm. The scene is prepared for the lead up to the Battle of Loos (officially September 25 -29, but it dragged on into October).

HW was not present at this battle himself (his training continued back in England) but he did meticulous research into the details, using the detailed information given in the Official History that he bought while writing this volume, together with several books on the battle written by others who had been present. His writing is a superb evocation of the life and times of the era: totally authentic and correct and the reader is held present at all times within the action.

A detailed analysis of the battle and HW’s very correct treatment of it can be found in HWSJ 43, September 2007: Ian Walker, ‘Henry Williamson, F.O.O. and the Battle of Loos’ (pp.5-12) and Anne Williamson, ‘The spectre of Lone Tree’ (pp. 16-29), where various odd-seeming terms used are explained. This issue also contains an important overview by John Gregory, ‘The Great War in the Writings of Henry Williamson’ (pp. 68-91).

The Battle of Loos was the first time that the British used gas as a weapon of war: the Germans had used it earlier in the year with devastating results. It was a mark of genius to make Phillip a gas officer which gives him the freedom to move about and observe all that was going on – so giving the reader an overview of the whole battle.

Phillip’s task is the organisation of moving and placement of the cylinders of liquid chlorine gas. This is supposedly in great secrecy (the horses’ hooves were muffled in sacking so they would not be heard), but as usual the Germans knew all about it and were taking precautionary measures. There is much emphasis on the all-important aspect of wind direction, which will determine whether the gas will be blown toward the Germans or back onto their own troops with dire result. Comic relief (in true Shakespearian fashion) is added by ‘Twinkle’, Phillip’s batman, who rather sadly ends up being arrested as a deserter.

Phillip is attached to Spectre West’s section, and the two men have a good rapport. Spectre’s sharpness clarifies Phillip’s own thoughts and organisation. When he gets the order for timing of gas release, we find Spectre intensely worried: he knows the wire has not been cut (despite constant bombardment) and that the wind is wrong and that the attack will fail.

Back at Army HQ, General Haig is seen as also intensely worried about the wind speed and direction – using cigarette smoke as his guide. Knowing the conditions are not good enough, Haig tries to get the release of gas stopped, but is told that it is too late, orders must stand. (These details are all authentic.)

So at zero hour – 5.50 a.m. – the gas is released and the attack commences, with resulting total chaos. The Gaultshires are decimated. West is ordered to make another direct attack which he knows will not succeed; so he decides on an outflanking manoeuvre behind Lone Tree. With the colonel and adjutant wounded, West is in command; but also wounded, he orders Phillip to lead this attack.

He successfully carries out the attack, to his relieved surprise finding no resistance: all the Germans surrender. Captain Douglas (Phillip's former sergeant in the London Highlanders) arrives and takes charge, claiming the prisoners, but he too is hit and falls, his kilt askew, revealing his ‘bloody backside’. (This actually happened to Douglas Bell, who had by then transferred to the Cameron Highlanders, the ‘Cameroons’, thus wearing a kilt, as he relates in his own Soldier’s Diary of the Great War, using the words quoted.)

Phillip also sees at Lone Tree a scene of the London Highlanders lying wounded or dead with their kilts round their waists and white bottoms exposed: there is an Imperial War Museum photograph of this scene within HW’s archive.

Having sustained a whiff of gas, Phillip is put on light duties, a further useful structural device which enables him to wander about and observe the action. He hears the Cantuvellaunians (left behind at Heathmarket where they appeared to be a permanent fixture) have been seen, and goes off to find them. They are part of the missing Reserves (held back by Field Marshal French) and are lost and totally out of depth now they are in the ‘real war’. The previously despised Phillip now leads them to their placement where they open their orders to attack (actually by then cancelled): without any support they are decimated. Phillip is knocked unconscious temporarily and finds himself surrounded by Germans and a prisoner. But the Germans say that there are so many wounded they cannot cope, and send them back to their own lines.

In charge of a group of men on the way back, along with thousands leaving the battlefield, he meets the Coldstream Guards coming forward, his Cousin Bertie among them: an angry scene ensues which includes one guardsman cracking a hunting whip at men as they urge them to rally (again a true incident), but Phillip manages to explain the situation to Bertie, and he continues on his way back while Bertie goes forward.

Phillip decides (with extreme daring and great ingenuity) to watch the next attack from the landmark known as ‘Tower Bridge’ (the headgear of the pre-war colliery), passing the important ‘Double Crassier’ (slag heaps) on the way, from where he can see the soldiers engaged in fighting, and mainly falling, in the distance. This is a superb piece of ‘overview’ (in all senses) coverage: made more poignant by the discovery of a swallow’s nest. Having watched and described in detail the attack of the Guards from this precarious tower position, so recently held by the Germans, he is startled by a movement and terrified that a German soldier has also climbed the tower:

To his relief he saw that it was a swallow, flying round and round inside the turret, crying with beak open above the tawny stain on its throat, crying inaudibly. Looking up, he saw a nest upon one of the roof girders, in a space where it was crossed by a lighter length of iron. There was the lip of grey mud, dry grasses showing, and shrunken marks of droppings on the floor.

He climbed on the table, and felt in the nest. It had young, a late brood . . . The swallows would be migrating soon; the little ones would be left behind. He thought of the tragedy of the parents, torn between love and the urge to migrate when the inner call came to leave. . . .

The hen bird slipped through the open window, and he saw her flying in the air, catching flies. He thought it wonderful, that in all the noise, she had carried on; . . .

The attack of the Guards had become a feeling of mourning . . . He felt empty and weary. [As he leaves –] One last look at the nest on the rusty iron girder, bon chance, mes hirondelles!; and slinging haversack and water-bottle, he left the turret.

After the battle the Germans quickly completely demolished ‘Tower Bridge’ so that the British could not use it as an advantageous observation post against them.

On his return to base Phillip finds his batman Twinkle has been arrested (he is a deserter – and so will be shot) and he also is temporarily arrested, but this is sorted, and he is attached to the Gaultshires as an acting company commander.

The battle continues but soon he is told that his posting to the Diehards' 'navvies battalion' has actually come through and he is to return to England. While he is at Béthune station waiting for his train, he learns that Cousin Bertie has been killed at the attack on Hohenzollern Ridge, and is buried at Vermelles.

Back in Trafalgar Square in London, he watches a meeting of the Suffragettes, ‘Stop the War’, led by Sylvia (Pankhurst) and spots his Aunt Dora watching. She has dissociated herself from this movement now, because of their anti-war attitude. He tells her of Bertie’s death, her sadness being partly for Bertie’s father Sydney, killed in the Boer War, with whom she had been in love. He also tells her the sad tale of Twinkle, to find she knows of his widow, one of her cases now facing dire straits. The strategy may be a little clumsy – but it does allow the chance for the plight of those women and families struggling after the death of the male provider to be recorded: part of the social history aspect of HW’s series.

As stated HW himself did not take part in the Battle of Loos – and Phillip's return to England in the novel takes up what happened in real life, as will be revealed in the next volume.

Phillip then returns home, calling in to see the Rolls family, and finds them all very upset about Bertie’s death. Cousin Polly is staying at his home, but he goes off to Freddie’s bar where he finds Tom Cundall (Victor Yeates) in pilot’s uniform and Eugene (Desmond Neville’s Brazilian friend). They go out on the Hill to watch for zeppelins. When he returns home, Polly gets dressed (on the stairs and showing her knickers!) and they go out again on to the Hill and lie down together.

Richard Maddison, meanwhile, is patiently and exhaustedly doing his nightly round of duty as a special constable, wishing he had his dark lantern, given to Phillip years before, on which to warm his hands.

|

|

A gaunt-looking William Leopold in his special constable's uniform |

*************************

Index and Chronology to A Fox Under My Cloak: Maps and Chronology and Index

Between 2000 and 2002 Peter Lewis, a longstanding and dedicated member of The Henry Williamson Society, researched and prepared indices of the individual books in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight series (the first three volumes being indexed together as 'The London Trilogy'). Originally typed by hand, copies were given only to a select few. His index to A Fox Under My Cloak is reproduced here in a non-searchable PDF format, in two parts, with his kind permission. It forms a valuable and, indeed, unique resource.

*************************

Click on link to go to Critical reception.

*************************

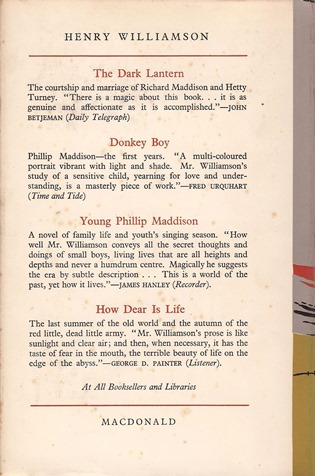

The dust wrapper of the first edition, Macdonald, 1954, designed by James Broom Lynne:

Other editions:

|

|

|

|

Panther, paperback, 1963; and back cover. This, and the next three novels published by Panther, used on their covers the atmospheric and realistic contemporary drawings of Chevalier Fortunino Matania R.I. |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Chivers, for The Library Association, hardback, 1983 |

Macdonald, hardback, 1985 | Sutton, paperback, 1996 |

The Macdonald cover features 'A Street in Arras' painted by John Singer Sargent in 1918; the Sutton cover is a detail from ‘The Triumph of Death’ (c.1562) by Pieter Brueghel the Elder (c.1515-69).

Back to ‘A Life’s Work’ Back to ‘How Dear Is Life’ Forward to 'The Golden Virgin'