A CHRONICLE OF ANCIENT SUNLIGHT

A novel in 15 volumes, first published by Macdonald & Co., 1951–1969

A note on the Chronicle book cover designs

The series opens in 1863, and goes on to cover the story of Phillip Maddison and that of his family and friends through the first half of the twentieth century, including two world wars and a great deal of the social history of the period. The series, in fact, roughly follows HW’s own life – but with considerable fictional embellishment. Comprising the best part of 3 million words, the work is a tour de force and has to be one of the great achievements of English literature. It was a mammoth and exhausting task, with a volume appearing nearly every year, the author proof-reading one volume while writing, adding, deleting, and honing, the next.

Born in 1895, HW was in his mid-fifties when he finally settled down to write this magnum opus. But it had been in – and on – his mind from the very start of his writing career. There are mentions in his earliest notes and Phillip Maddison, the chief protagonist of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, has, as the London cousin of Willie Maddison, several cameo appearances in the early Flax of Dream series, published between 1921 and 1928.

In the early 1920s, as he began his writing career, HW kept a comprehensive journal in a large folio volume dedicated to Richard Jefferies. (For further explanation about this Journal see references in the entries for the early books.) In March 1947 he was obviously re-reading this Journal and he made several explanatory notes in the margins in red ink (the first one is dated March 1947, and they were all obviously written at that time). Next to an entry under 4 May 1920, which concerns a visit he made with ‘Sweet Doline’ (Doline Rendle, then current love of his life) to see all the birds’ nests he had found, is the following:

My intention at this time [1920] was to double my characters of the Flax. Thus Phillip is the London cousin of William, and ‘Spica’ [Doline Rendle] is a London cousin of Mary Ogilvie. I wanted to show the difference in the psychical make-up of the country-bred person, and the town-sharpened (warped) consciousness. Thus while Mary accepts William naturally and without reserve, Spica has the same feelings for Phillip but cannot let them open naturally, with contentment: her “first seven years” were to her spirit as the acid soil of cities is to grass & trees and air. Polluted.

That comment follows HW’s general ideas about the ideal growth (education) of body and mind within a natural environment which were particularly marked when he was a young man. Naturally, that original synopsis became modified by the time HW actually came to write the new series.

Then in various places throughout the intervening years HW notes in his diaries and his letters to various friends, increasingly as time went on, his anguish that he had not started; has not been able to start; is being prevented from starting, this work, which he so obviously considered from the beginning would be a major work.

A notable example of this appears in a letter to T. E. Lawrence, dated 24 March 1930, just as his (very successful war story) book The Patriot’s Progress was to be published:

Damn! I wanted 60,000 words recreating the Etaples mutiny; now I’ve popped it off in 600 words. I used all the stereotyped details of war books: reserving the fresh ones for my real war book, which has the war as background (often close background) and the human figures always moving just in front of it. 500,000 words – 1894-1924. The Hopeful Life. 3 volumes. I’m flinching from beginning.

For a long time it is noticeable that he is envisaging the proposed work as ‘3 volumes’. He reiterates this in Goodbye West Country (1937), referring to ‘my London trilogy’. And as can be seen in that 1930 letter, his timescale is 1894–1924. But as the years passed and the work was still not begun, it is obvious that his scope was enlarged. And once the Second World War had occurred, reinforcing all the problems engendered by the earlier war, he surely had to include it. The catastrophic flood of Lynmouth in August 1952 gave him the perfect scenario to use as his climactic conclusion. There was/is an inherent momentum which carried/carries the story forward to a certain point, which made/makes a perfect circle. It would seem as if he was not meant to start it earlier. Certainly the delay, however frustrating it must have been to his psyche, allowed him to grow into full maturity as a person and therefore as a writer. It could not have been otherwise.

As the Second World War ended, so HW’s twenty-year marriage to Loetitia Hibbert broke under the tremendous strains that it had endured. HW was in a state of mental turmoil and breakdown, in many ways as bad as at the end of the First World War, but for different reasons. His personal papers reveal that in the summer of 1945 he tried to commit suicide on the beach at Putsborough, but was rescued literally and psychologically by two men who were to become great friends. He was mentally and physically exhausted from the work and strain of running his Norfolk Farm and writing to provide the income to keep it going. He was also extremely disturbed by the perfidy of Hitler and the knowledge of the atrocities that the Nazis had perpetrated. The Norfolk Farm was sold, and at the end of October 1945 the family moved to a house in the village of Botesdale, near Diss, on the borders of Norfolk and Suffolk. Divorce had been agreed, but HW wanted all to be done as amicably as possible (although that was basically for selfish reasons). To begin with, although often absent, he was ostensibly domiciled at the Botesdale home (where he took over the once servants’ quarters for his writing), but on filing the divorce on 2 October 1946 he had to finally vacate the marital home, and he went back to live in Devon in the Writing Hut in his Field at Ox’s Cross, above the village of Georgeham. His father died at this point, and although HW felt considerable anguish over this he also felt ‘free’ at last from his father’s dominating critical presence. He actually expresses this feeling of ‘freedom’ in the climax of the last volume of the series, when the fictional Phillip at last feels he will be able to write the series of books he has been planning since the 1920s, thus forming a perfect circle – symbol of eternity.

HW’s main writing occupation at this time was The Phasian Bird (published in November 1948). It has to be significant that at the end of this book he kills off the main character, Wilbo (again based on himself), as well as the almost mythical Chee-kai – the magnificent Reeve’s pheasant (which has a near magical persona reminiscent of The Firebird). With Wilbo dead, HW is therefore literally and symbolically ‘free’ of everything in his past life. He has sloughed a skin and is beginning again. Those ‘red ink’ notes made in March 1947 in his ‘Richard Jefferies Journal’ show that he was already actively thinking about beginning, at last, his great work. He was reminding himself of those early scenes, filling his mind with their details, so that he could lose himself and so find that ‘lost time’ (the Proustian ‘à la recherche du temps perdu’ – for him, ‘Ancient Sunlight’).

HW had become friends with Malcolm Elwin, a writer and critic who lived at Northam Burrows on the spit beyond Westward Ho! in north Devon. At Easter 1946 HW met Elwin’s sixteen-year-old step-daughter, Susan Conelly, and suddenly and completely (as always) had fallen in love with her. Over the ensuing months this caused him great anguish: it also caused considerable tensions between him and the Elwins. But Malcolm Elwin was a staunch supporter of HW’s writing, and did not let this affect his literary judgement. He had just taken on the editorship of the West Country Magazine and published two of HW’s stories in the first issue in summer 1946. Ann Thomas, HW’s long-term secretary and mistress, came back to work for him in mid-1947, typing The Phasian Bird, and undertaking the work involved when HW now took over from John Middleton Murry, another friend and great supporter, the ownership and editorship of the literary journal The Adelphi.

But in the summer of 1948 HW met a young teacher, Christine Duffield and fell in love again. He abandoned The Adelphi and Ann Thomas, and, not without some interim drama, he and Christine were married in April 1949. HW was being given a new start in every sense of the word.

During the war he had prepared what he considered to be a sequel to his book The Story of A Norfolk Farm, a volume covering the farm during the war years, which he tended to call ‘Wit’s Misery’, and/or ‘A Chronicle Writ in Darkness’. He now thought to prepare this for publication, but he had also begun writing what was to be the first volume of the new work.

This double project was obviously causing him problems, and he wrote to Malcolm Elwin with his woes. In Sept 1949 Elwin wrote to him to tell him to leave the book on the Norfolk Farm alone and to get on with the new work.

Your job is the saga of Phillip Maddison . . . [which] would lift you into the top rank of big novelists.

HW obviously took this to heart for in November, Elwin wrote again, noting:

Great news that you are now 24,000 words down the road to the Mecca of your career. Aye, indeed, will I be honoured by the dedication of your first volume.

At this point HW had a large disagreement with his long-term friend and publisher, Richard de la Mare at Faber. Richard did not want to publish the farm sequel, nor was he prepared to give an advance on the unknown new book. It is obvious that both lost their tempers and said unforgivable things. HW was enormously upset by this event. It was of course, a crucial moment for him psychologically, for his extremely fragile, nervous, and sensitive temperament needed extra support to prop him up over the new venture.

In great distress, he rushed straight round to his current agent, Cyrus Brooks (of A.M. Heath & Co.), who recommended that he take the work elsewhere. HW immediately went round to Collins who had been his original publishers, who agreed to take the new work on. A contract was signed, and HW received an advance of £500, with a further £500 to be paid on delivery of the typescript. But in September 1950 he learnt from Cyrus Brooks that Collins did not like the new book (The Dark Lantern) because they found its hero, Richard Maddison, unsympathetic. HW noted that he was meant to be unsympathetic, that it was to show how all future events stemmed from the father/son relationship. (He had read Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son, which reinforced his own theories.) But it is evident that he had not explained his overall plan for the new series to Collins, for Richard Maddison was not to be the main character.

HW was at that point about to depart with his new wife Christine to France, to stay with the writer Richard Aldington (whose biography of T. E. Lawrence was to cause such a furore in due course) for a holiday – (a repeat of their honeymoon visit the previous year. Their son, born in May 1950, had been left at Botesdale with his first wife, Loetitia – the last child of their marriage being then five years old.

Distraught, HW then rushed round to Faber with the rejected typescript. Richard de la Mare was somewhat cold (they had not – and never really did – made up their differences from the argument), but he did agree to look at it. However, while HW was in France he wrote to say that he too did not like the main character.

On holiday and now more relaxed at this point, HW decided to rewrite where necessary. On return to England he settled down to his task, objectively making Richard Maddison a more sympathetic character, and what was by now the fifth version was sent to Collins in mid-December. But Collins still stalled, and did not pay over the next amount of advance royalties.

That HW poured out these problems to Malcolm Elwin, now on the editorial staff of Macdonald & Co., becomes obvious, for on 18 February 1951 HW received a letter from Elwin saying that his firm were willing to publish the new series.

The news engendered a flurry of telegrams to Cyrus Brooks to arrange cancellation of the contract with Collins. They very generously only asked for £150 of the original advance to be repaid – although they were of course partly to blame for the situation.

But HW now nervously decided to doubt Elwin’s judgement and lost faith in himself and in the new work. He decided to send the typescript to a new acquaintance, who had written saying how much he admired HW’s writing. This was George Painter (Keeper of Manuscripts at the British Museum), who wrote reviews for The Listener and the New Statesman (and went on to write several biographies, notably of Marcel Proust, André Gide, and Chateaubriand, all of which won prestigious literary prizes). Painter passed the work as excellent. So, reaffirmed, HW signed the contract with Macdonald on 15 February 1951, receiving £500 on signature, and a further £500 on delivery of the typescript.

The stage was now set for the publication of what eventually became the very long cycle of novels that comprise A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight. Malcolm Elwin was a tower of strength as HW’s editor, although HW inevitably became increasingly irritated when Elwin made criticisms with which he did not agree. Over the next nineteen years Macdonald published one volume almost every year. It was a gargantuan task, and was, and remains, an enormous achievement.

George Painter, in an essay entitled ‘The Two Maddisons’, written in 1959 and published in The Aylesford Review (vol. II, no. 6, Spring 1959, pp. 214-18) (by which point seven volumes of the Chronicle had appeared) stated:

All great writers have something in common – a sense of power and vision, a moment of grace and revelation made permanent – which is communicated from them to the reader. . . .

The peculiar quality of Henry Williamson is the piercing directness of his vision, the absolute identity of his own feeling and its communication to the reader, the clothing of a naked and terrible pain or joy in a noble and innocent prose, as keen as sunlight and as transparent as spring-water. He stands at the end of the line of Blake, Shelley and Jefferies: he is the last classic and the last romantic.

Williamson has been compared with Proust [e.g. Malcolm Elwin, ‘Henry Williamson: An English Proust’, The Aylesford Review, vol. II, no. 2, Winter 1957-8, pp. 42-48] . . . the two writers have a real affinity in their vision of the past as the place in time where the truth of things and people . . . can be seen as pure and undying. The two ideas of Time Lost and Ancient Sunlight, though independently discovered, are intimately related; and Williamson could say of this aspect of his work, as Proust said of his own, ‘my instrument is not a microscope, but a telescope pointed at Time’. . . . [Painter’s biography of Proust appeared at this time] ‘A man’s life of any worth is a continual allegory’, said Keats; and the corollary follows that a great writer’s works are his attempts to detect and tell the allegory of his own life.

Phillip Maddison is a divided man, sometimes cruel, cowardly and sinful, sometimes possessed of courage, kindness and insight, moving towards a still unknown salvation, and seen with complete clarity and charity by a man who has become whole [i.e. HW as the writer].

But this vast novel-cycle, the summer-harvest of Henry Williamson’s life as a writer, is not only the study of an individual character. In art the universal is sometimes, perhaps best, revealed by a profound and minute examination of the particular. Here is an unrolling map of the labyrinth of three generations, our fathers, ourselves, and our children, and the thread leading to the mystery – monster of divinity? – at the centre. . . . The whole cycle will ultimately be recognised as the great historical novel of our time, its subject as the total experience of twentieth century man.

Father Brocard Sewell, the editor of The Aylesford Review, and a great champion of HW’s work, had devoted an entire issue of the magazine to HW (vol. II, no. 2, Winter 1957-8). One of the articles was the essay by Malcolm Elwin, noting HW was the English Proust: another was by John Middleton Murry, once married to Katherine Mansfield until her early death from tuberculosis, and great friend of D.H. and Frieda Lawrence. Murry was an eminent critic and writer, and also a pacifist who ran a ‘Community Farm’ in East Anglia. From 1923 he had edited the prestigious magazine The Adelphi, which in 1948 he had handed over to HW as previously stated. [A full background on John Middleton Murry and his friendship with HW can be found in Anne Williamson, ‘Millennium Revelations: John Middleton Murry (1889-1957)’, HWSJ 35, September 1999, pp. 38-66.]

Murry’s essay was called ‘The Novels of Henry Williamson’ and contains major insights.

Here and there a man of more than ordinary sensibility arises for whom to forget [the horrors of war] is an impossibility. The experience of war becomes a festering wound in his psyche for which the rest of his life is a quest for healing. . . . Such a one is Henry Williamson. And my purpose is to draw, if I can, the attention of a reluctant world to the rare quality of the series of novels he is now writing . . . this will be in its entirety one of the most remarkable English novels of our time. . . . It is amazingly rich in all the living detail of a swiftly changing society; the characters are drawn with such loving sympathy and such firmness of imaginative outline that we are entirely absorbed by their vicissitudes. We are apprehensive for them, we are relieved; we rejoice and are sorrowful; we are angry and we understand and we laugh and laugh again. To be able to do this with us is the noveliest’s supreme gift. . . .

I believe it is high time we awoke to the splendour and scope of his effort and achievement in A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight. Begin with The Dark Lantern and read on: you will be the richer for it.

This essay was printed in an expanded form in J. Middleton Murry, Katherine Mansfield and Other Literary Studies (Constable 1959), with a foreword by T. S. Eliot, which appeared after Murry’s death in 1957 and was compiled by his wife. Apart from the important Mansfield essay and the one on HW, the only other essay is on George Gissing, erudite Victorian writer.

Mary Murry states in her ‘Compiler’s Note’:

The series of novels by Henry Williamson were very highly thought of by John Middleton Murry. He considered it of real importance that Henry Williamson should be fully recognised as one of the great novelists of the generation and therefore was most anxious that this essay should be published.

The essay was reprinted by the Henry Williamson Society in 1986, and though long out of print The Novels of Henry Williamson has now been made available again by the Society as an e-book.

One must state here that, at the point both Painter and Murry wrote those critiques, only the first seven/eight volumes had appeared. But both knew HW well and were privy to his plans and ideas for the rest of the series, which makes their comments valid for the series as a whole.

In the expanded book version (which examines HW’s whole opus to that point) Murry also comments:

They [the ‘Chronicle’ novels] are the products of a creative transmutation of fact into truth, like Goethe’s Dichtung und Wahrheit [Fiction and Truth, or, The Novel and Truth]. It is the work of a truly gifted artist, come at last, after much inward travail, to a mastery of his own self-disturbing powers, and working on the grand scale. . . . He was waiting to see the past with the vision of the timeless truth of art wherein it should become truly universal; to see it with clarity and charity, with a mind purged of resentment and the urge for self-justification . . . seeing the past, in the clarity of Ancient sunlight, which is Truth.

A later judgement is by the late Alan Clark (MP, eminent historian and great supporter of HW’s writing) in a review of that excellent book by Martin Gilbert, First World War, (Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1994) in the Guardian, 13 September 1994 (and also printed in the Evening Standard), where he referred to the Chronicle as:

Still far the best illustration of history as fiction that I have ever encountered.

Most of the series was reprinted in paperback by Panther in the 1960s (while original volumes were still appearing) – though they stopped at A Solitary War. The entire series was reprinted in hardback by Macdonald in 1984/5, while there was a full paperback edition published by Alan Sutton Publishing in their Pocket Classics series in 1994–99. Some individual titles (mainly the First World War volumes) have had multiple reprints. The series is currently available from Faber through their print-on-demand series Faber Finds, and from the same source, as e-books.

*************************

Today we know a great deal more about HW and his writing life, and A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight in particular is viewed from a very different perspective to that of the early 1950s. We know the series as a whole unit, and have an understanding of HW’s purpose and vision.

When HW settled to writing the series the situation was very different. The country itself was still recovering from the Second World War: austerity was very evident and people were still gripped by shock and grief. The revelations of the atrocities of the Nazi regime under their leader were a raw wound on the psyche of the nation. A pivotal turning point in attitude was probably the 1951 Festival of Britain. Although this had a serious purpose, for most people it was a chance – the first chance for a very long time – to be frivolous. The mood changed: people needed and wanted to be cheered up.

HW’s readers would have known that he had farmed during the Second World War, and many would have been aware of his numerous articles and broadcasts about farming, but he was still most known as a nature writer. Immediately post-war there was a large number of reprints of earlier titles. In 1945/6 Putnam re-issued a new uniform edition of his five nature books – Tarka the Otter and Salar the Salmon heading the list as always. His early ‘Village Books’ were re-hashed and re-published under new titles. New editions of The Gold Falcon and The Star-born were also published.

His most recent new works were The Phasian Bird (1948), at heart another nature book, but with powerful allegorical content, and the somewhat quirky Scribbling Lark (1949), again with hidden (but totally different) allegorical content.

It can be seen, therefore, that there had been no actual hiatus in his production of books. Equally, one can see why publishers would have been wary of his new proposal. The world had changed radically from its pre-war attitudes. Publishers could no longer afford to indulge an author’s idiosyncrasy because he was a good writer: the financial side was now of prime importance (and was to become increasingly so). It was all to do over again for someone as morbidly and mordantly sensitive as HW.

A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight is written as one long story with deliberate minimum apparent internal structure between individual volumes. This method is known as a roman fleuve: a story which flows like a river from one volume to another. As the Chronicle also expresses philosophical ideas, it can also be termed a ‘thesis’ novel. But such technicalities belong to theoretical criticism. They do not affect the reader of the work itself.

One of the main aspects of the Chronicle, apart from its being an extraordinary and absorbing novel, is that it gives a detailed picture of the life of an ordinary family over the first half of the twentieth century. It is a picture of the social history of that time: one in which, due to the power of its author, we live as intensely as if it were happening to ourselves. One of the main themes is the plight of agriculture, another is suffrage: the politics of the late 1930s are interwoven into the later volumes. Transport looms large – especially Phillip’s obsession with fast cars (echoing HW’s own predilection!). The whole is bound together not just by Phillip’s life story, but by HW’s power of description of the natural world and its many facets – large sweeps of the brush setting scenes as if backcloths of allegorical plays, but filled also with the myriad minutiae of the tiniest detail of plants and insects and birds and animals. The work is indeed a masterpiece.

Opening in a London suburb still fairly rural in nature, these scenes are expanded in the first three volumes (known as ‘The London Trilogy’), while the content of the next five is devoted to the First World War (these volumes are considered by many to be among the very best writing on that war). We are taken through Phillip’s difficulties in love and writing: his first idyllic marriage ending in the tragic death of his beloved Barley in childbirth (an entirely fictional event); his struggle to become a writer; a second marriage and family; his first farming venture on the family estate which ends in failure – and then his second attempt in Norfolk during the Second World War and his involvement in the politics of Hereward Birkin (Oswald Mosley); and the amazing climax of the final volume culminating in the catastrophic flood that devastates Lynmouth on the North Devon coast, which finally releasing Phillip from his demons, so that at last he can begin his long-planned great series of novels. Thus HW brings us full circle.

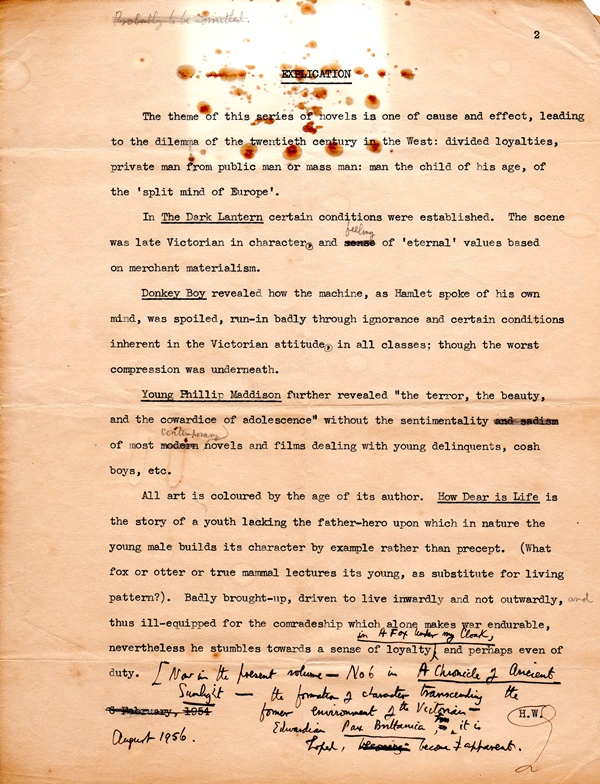

HW’s own illuminating thoughts on his series can be found in his essay 'Some Notes on The Flax of Dream and A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight'.

This essay was first printed in the Aylesford Review, Vol II, No. 2, Winter 1957-'58. Ed. Fr. Brocard Sewell. (The issue is subheaded: 'Henry Williamson: A Symposium & Tribute'.) It was reprinted in Henry Williamson: The Man, The Writings: A Symposium (Brocard Sewell, ed., Tabb House 1980); and again reprinted in 'Some notes on "The flax of dream" . . .' and other essays (Paupers' Press, 1988; The 'Aylesford Review' Essays, Vol. 2)

See also: Fr. Brocard Sewell, 'Some Thoughts on Henry Williamson's "The Flax of Dream"' (Aylesford Review, Vol. VII, No. 2. Summer 1965), being an Address given at University of Exeter, May 1965, on the occasion of the Presentation by HW of a selection of his MSS 'Devon works' (Tarka the Otter, Salar the Salmon etc.).

*************************

Links to discussion of individual volumes are given below – click on the image to take you to the page:

*************************

Indices to the books comprising A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight

Between 2000 and 2002 Peter Lewis, a longstanding and dedicated member of The Henry Williamson Society, researched and prepared indices of the individual books in the series (the first three volumes being indexed together). Originally typed by hand, copies were given only to a select few. They are reproduced here as non-searchable PDFs, with his kind permission. Where chronologies were compiled, these are also given when useful. The sometimes lengthy synopses (with Peter Lewis's delightfully idiosyncratic asides) are not included, as essentially they repeat information already given in Anne Williamson's considerations. The indices form a valuable and, indeed, unique resource.

|

'The London Trilogy': The Dark Lantern, Donkey Boy and Young Phillip Maddison The PDF is in two parts: |

||

|

A Fox Under My Cloak Chronology and Index |

The Golden Virgin Chronology and Index |

|

|

Love and the Loveless Chronology and Index |

A Test to Destruction Chronology and Index |

The Innocent Moon |

| It was the Nightingale | The Power of the Dead | The Phoenix Generation |

| A Solitary War | Lucifer before Sunrise | The Gale of the World |

*************************

A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight: book cover designs

James Broom-Lynne (1916-1995)

The striking covers of the fifteen volumes comprising A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight were designed by James Broom-Lynne, an illustrator of note. He had attended St Martin’s School of Art in London, and after service with the Civil Defence during the Second World War was engaged in illustrating and advertising work.

Broom-Lynne specialised in book jacket design and the list of his work in this field is impressive, including covers for the novels of H. E. Bates, Anthony Powell, Paul Gallico, Geoffrey Household and Edith Pargeter among others. He also wrote several novels and a handful of plays.

There is some evidence that HW suggested ideas and provided sketches for at least some of his titles, but unfortunately there is nothing in HW’s archive to give any clue about the background of this important connection. It was evidently instigated by his publisher Macdonald – and indeed Broom-Lynne was their art director from 1966-69; although by then HW’s Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight was in its last phase.

Broom-Lynne also designed the cover and provided charming vignettes (which are very reminiscent of Charles Tunnicliffe) for HW’s Tales of Moorland and Estuary (Macdonald, 1953).

Chevalier Fortunino Matania, RI (1881-1963)

The striking covers of the Panther paperback editions of the war volumes of the Chronicle published in the early 1960s are reproductions of the work of the Italian artist Fortunino Matania. Talented from a very young age, Matania was invited to England in 1902 to do a painting of the coronation of King Edward VII (and subsequently covered most royal occasions from that time up to our present Queen’s coronation). He took a job on The Sphere, where his illustrative work included the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. He was a war artist in the First World War, being acclaimed for his realistic paintings and drawings of trench warfare. His work adorning the covers of these Panther paperbacks raises the books to collector-item status.