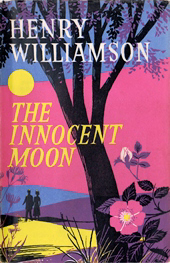

THE INNOCENT MOON

(Vol. 9, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight)

|

|

| First edition, Macdonald, 1961 | |

Henry Williamson and Kit Williams in the Pyrenees, 1929

First published Macdonald, 27 October 1961 (18/-)

Panther, paperback, revised text, 1965

Macdonald, reprint, 1985

Sutton Publishing, paperback, 1998

Currently available at Faber Finds

Dedication:

‘TO WILLIAM KEAN SEYMOUR’

The title of this volume is taken from the poem Sister Songs (1895) by Francis Thompson (1859-1907) the mystical metaphysic and one of HW’s chief ‘mentors’, to whom he felt close affinity. His Aunt Mary Leopoldina (Theodora of the novels) had given him a copy of Thompson’s poems during the First World War, which had made a deep impression on him. HW became the President of The Francis Thompson Society in the early 1960s and wrote two major essays on his work (see entry in due course.)

The content of The Innocent Moon is very close to that which appeared in a different form in the earlier The Sun in the Sands (1945), where in chapter 4 he wrote:

In myself, I believed, was a power and vision and truth clearer than in any other writer in the world, except in Richard Jefferies, William Blake, and Francis Thompson.

In all I work, my hand includeth thine;

Thou rushest down in every stream

Whose passion frets my spirit’s deepening gorge;

Unhoodst mine eyas-heart, and fliest my dream;

Thou swing’st the hammers of my forge;

As the innocent moon, that nothing does but shine,

Moves all the labouring surges of the world.

(‘Eyas’ is the term for a young falcon: training a falcon involves keeping them hooded for periods of time, and only unhooded when sent to fly after prey.)

HW had also written this poem out at the front of his own copy of The Star-born (1933), where he added underneath: ‘Francis Thompson, who passed to dream tryst, 13 Nov. 1907.’

*************************

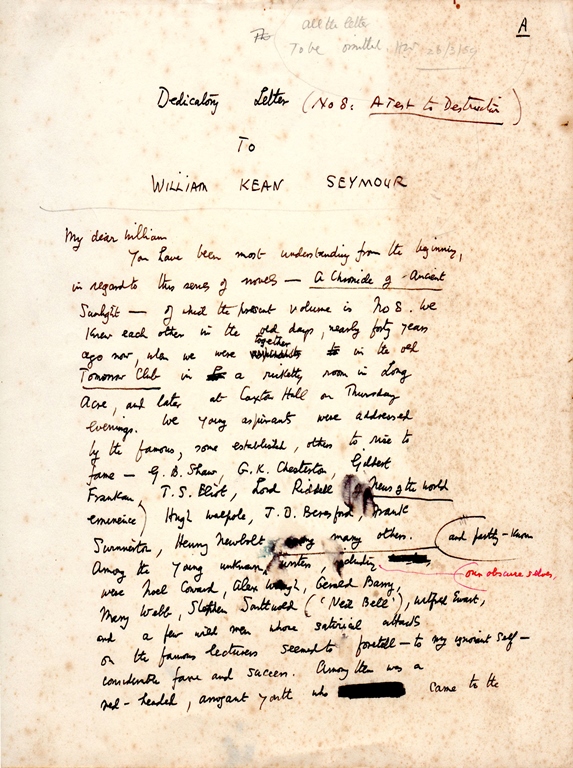

The dedication to William Kean Seymour in the first edition is rather oddly placed on the reverse side of the title page, and sandwiched between the usual bibliographical details. That HW appears to have originally intended to dedicate the previous volume (A Test to Destruction) to WKS can be seen from his manuscript ‘Dedicatory Letter’ where we learn that the two men had first met at The Tomorrow Club in 1920, although HW does not mention Seymour’s name anywhere. Neither does there appear to have been any approach to Seymour regarding this book, for his letter of acceptance is dated 26 November 1960, when A Test to Destruction had already published, and it shows no sign of a previous approach. HW’s ten-page script is actually a ramble through his own literary career and would not ever have been suitable for its supposedly intended purpose (as he obviously realised!).

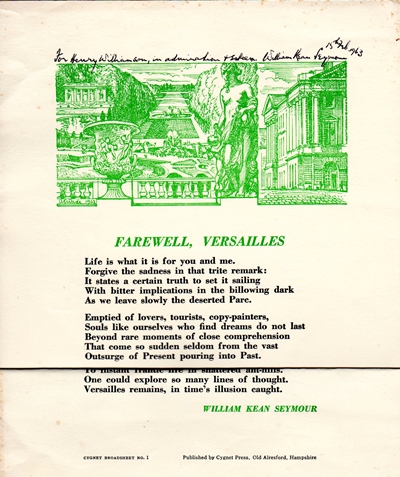

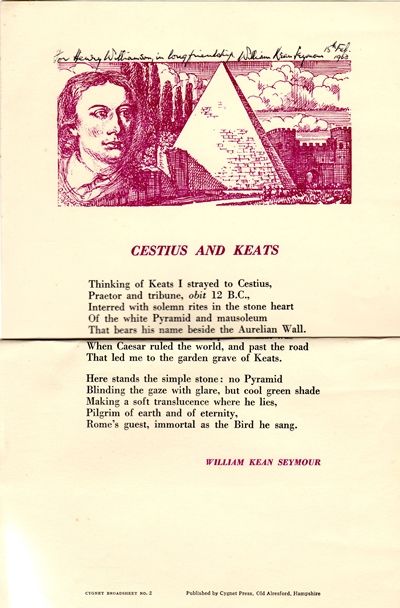

Seymour worked in a bank throughout his working life, but was also a novelist and wrote poetry. He was a member of the Royal Society of Literature, and indeed was the person who nominated HW for Fellowship of the Society in 1954. (HW’s ‘inaugural speech’ – ‘Some Nature Writers and Civilisation’ -- was made in October 1957, and has been reprinted in the collection Threnos for T. E. Lawrence, HWS 1994; e-book 2014.) Both men were founder members of the West Country Writers’ Association in 1951, though HW had been actually invited to join, and I think that is when they would have resumed their earlier acquaintanceship. WKS became vice-chairman (1965-72), then chairman (1972-74) of the WCWA (of which HW was President from 1960-65). The book of The First 50 Years of the WCWA (Anne Double, 2001) shows Seymour to have been a rather difficult and irascible man who often overturned committee decisions. He seems to have had an inflated idea of his own self-importance, perhaps reflected by the privately printed broadsheets of single poems that he sent to HW:

(Text of poems © Estate of W. K. Seymour)

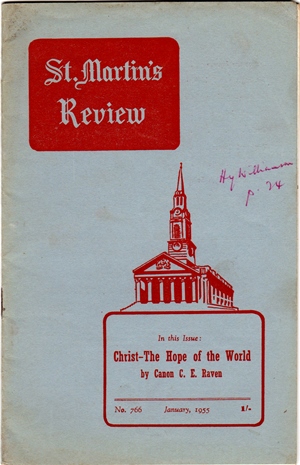

There is no evidence of any close relationship between these two. But Seymour did review the various Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight volumes as they appeared in St Martin’s Review, a small monthly magazine produced by St Martin’s Church, London WC2 (St Martin’s in the Field) which was mainly devoted to church matters.

Seymour’s second wife Rosalind Wade (herself a prolific novelist) gave a talk to the HWS AGM meeting in October 1986, but this did not shed any further light on the relationship.

*************************

The Innocent Moon opens in early 1920 and Phillip Maddison has determined to be a writer, having obtained (through an introduction by his grandfather, Thomas Turney shortly before his death at the end of the previous volume) a job in the Advertising Department of The Times – though the newspaper is not mentioned by name. His ambition advances to writing short articles for the Weekly Courier, but soon the paper has financial problems and Phillip is made redundant. Meanwhile, despite all the problems in the family home, he has been writing his first novel, using the ‘garden room’ of his grandfather’s house next door, now empty.

Taking his holiday in Devon, travelling down on his Norton motorcycle, he goes via the south coast where he finds himself in the village of Malandine, which he likes very much and where he rents a dilapidated cottage for £5 a year.

Back in London he joins the Parnassus Club and meets a young and beautiful young lady whom he calls ‘Spica’, with whom he falls in love; but the affair is strained and doomed from the start, and comes to an inevitable end.

After a few false starts, he learns that his first novel has been accepted. Life in the family home has always been difficult and now, after a final quarrel with his father and with his novel accepted, Phillip goes down to Devon to live in his rented cottage, together with his rumbustious friend Julian Warbeck. This results in a tempestuous and chaotic period which ends with Julian being asked to leave.

Meanwhile Phillip has met two other young ladies, both still schoolgirls and their mothers. First Irene Lushington and daughter Barley, and then Sophie Selby-Lowndes and family: daughters Annabelle and the older Queenie, and younger son Marcus: and the tale continues with the complicated relationships which arise.

After a hair-raising adventure in the Pyrenees, which includes superb descriptions of the scenery and situation, Phillip, when saying goodbye to Barley who is to return to her finishing school in France, proposes instead. Four days later they are married at Caxton Hall and travel back down to Malandine to begin married life.

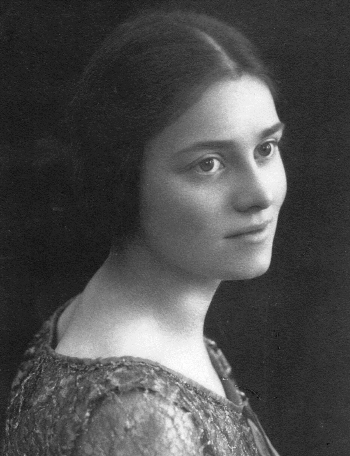

It is probably useful at this point to give the real-life names of the principal characters of the book so readers can cross-reference: ‘Spica’ is Doline Rendle, actually a cousin of Mabs Baker of the Folkestone era; ‘Julian Warbeck’ is Frank Davis, ex-pilot in the First World War, wild character, actually extremely shell-shocked; ‘Annabelle’ is Mary Graham Stokes, and the rest of her family is based on the Stokes family, whom HW met in Devon in 1922; ‘Barley’ and her mother ‘Irene’ did not really exist at this time – although Barley has elements of a later love affair.

|

| Doline Rendle |

|

||

|

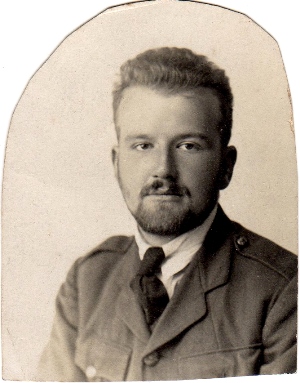

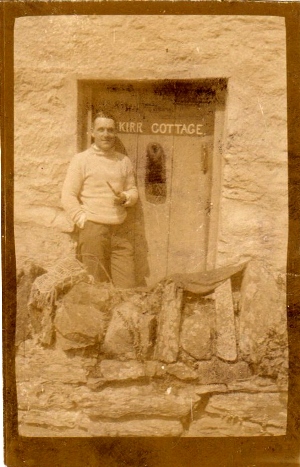

Frank Davis, still wearing his badgeless RAF tunic, in a photograph probably taken soon after the war's end |

|

| Mary Stokes |

That the villagers of Georgeham thought HW 'mazed' when he first came to live there is well known, and it is easy to understand how his bohemian lifestyle and behaviour at the time might have been thought by some to be inappropriate for an ex-officer and 'temporary gentleman'. His lack of regard for convention is perhaps illustrated by the photograph below. It is tempting to think that the two girls shown wading ashore after a swim au naturel are 'Queenie' and 'Annabelle'; however, the face of neither shows a resemblance to that of Mary Stokes, and so their identity remains a mystery!

*************************

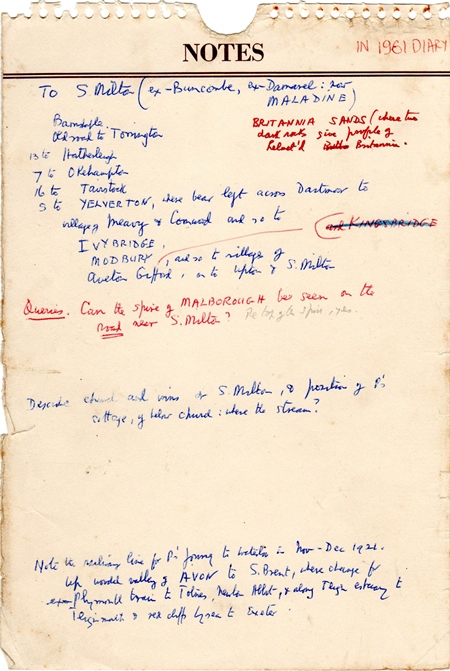

Having finished revising and correcting the typescript for volume 8, A Test to Destruction, and sent it off to Eric Harvey at Macdonald Publishing Company on 21 March 1960, HW recorded on 26 March (he was doing his Income Tax Returns): ‘I want to get on with No. 9 – to be taken from the Sun in the Sands.’

1 April 1960: I have been casting round for a line to take with No. 9. Made up my mind to cut Spica affair from The Sun in Sands & leave Phillip untrammelled for the Annabelle-Sophy complication after the Warbeck-cottage Part One, which is to begin after a brief description of Fleet Street, & then to the West Country. This will allow me to get the Straw in the Wind first part – marriage with Alethea as the climax. [This latter sentence refers to a MS/TS which describes his actual marriage with his first wife, Ida Loetitia Hibbert and which he did not use for this novel.]

2 April: Still casting for a line to run away on with No. 9. Have been looking at my 1920-21 Diary. [This is the ‘Richard Jefferies Journal’.] It should be left intact as a thing on its own, possibly for posthumous publication. [But see next entry!]

5 April: Read the 1920-21 Diary . . . I intend to quote most of the diary, as it reveals self-criticism in the most emotional parts – this is Ph’s balance.

6 April: Began chapter 1 of No. 9. It went easily, to typed page 9. Writing in the Hut.

7 April: Hut, writing. Continued to typed page 23. I am including some diary entries of my own (1920) with slight editings. It flows well & naturally, & establishes Phillip as a genuine nervous (near exhaustion) post war writer.

Then blank pages until:

24 April: Have been writing and enjoying No. 9. I am now ahead of the time-pressure to do these novels, a tension which has held me since 1950, or even before.

On 26 April HW left for Bungay (via Mary Murry, widow of John Middleton Murry, for tea).

27 April: Writing more of No. 9, with aid of my 1920 diary. [‘Rikky’ – his son Richard – there with fiancée (not AW!) – cinema, theatre, pub], all good fun.

2 May: Alarm woke me at 10 minutes before 4 a.m. Arose & had coffee from flask, sandwiches. Left quietly at 4.5 a.m. as planned [en route to London]. Day broke at 4.20 as before Hindenburg line (Bullecourt, 3 May 1917) attack. [Summer Time was first introduced in 1916.]

How little it takes to throw HW back into the First World War.

3 May: Had Foster White & Doline Rendle (‘Spica’) to dine at Studio Club before Aylesford Review party chez Mrs. Richard Rhys flat [Lady Dynevor and husband, patrons of the Arts, with whom he had become friends]. D. B. Wyndham Lewis & wife there [quite a coincidence in view of the content of Part Four of this novel] & Sir John Rothenstein, father of Mrs R.R. Walked with Doline after & found . . . [basically, she wouldn’t listen to what HW had to say] & this settled my perplexity of No. 9: & that youthful dilemma. [Sir John Rothenstein was a war artist during the First World War, and had painted the portraits that HW alludes to in earlier volume.]

4 May: Richard came up from Bungay. Wandered around Covent Garden market & looked over the gallery of Opera House at 3 p.m. to see the place-scenes of No. 9 novel. The Doves Nest is gone. In evening went with R. to the Llewellyn Rees Memorial Prize giving – R. was runner up [for his first book, The Dawn is my Brother]. Took him to dine at Studio club. Said goodbye – off tomorrow.

On 5 May HW returned to Devon.

6 May: On with No. 9.

But then he leaves for a visit to Wales and ‘Captain’ Child (who is Bill Kidd of No. 8 & Piston in No. 6 – and whose real-life character far out-ran anything HW wrote fictionally! The man was quite a rogue.); then to see Father Brocard Sewell, currently (teaching?) at a school there; then on again to visit Richard & Lucy Rhys at Dynevor Castle. The day after his return, 27 May, he attended the West Country Writers’ Association Conference held at Barnstaple, during which they made visit to HW’s Field. William Kean Seymour attended this as he wrote on 26 November when accepting the dedication for The Innocent Moon: ‘I had so little speech with you at Barnstaple and when I did we seemed not to “connect”.’

6 June: On with No. 9, which I enjoy. I appear to be free of fear and anxiety.

17 June: Have neglected this diary. Just slogging on with No. 9.

19 June: Have been working steadily on No. 9 & shall soon finish it. I am breaking down the Sun in Sands for it, & finding that book pretty awful. The rewriting of 1943 ruined the original truthful and simple & un-egocentric MSS I wrote in Augusta, Ga., [Georgia, USA] in 1934.

There follows several days of tirade-type entries: first to do with the Busby family (of his sister Doris who married Bill Busby – Bob Willoughby of the novels), who were in trouble in Africa: Michael (Doris’s son) was a schizophrenic, while the family was heavily in debt and needing money. (Sadly there seems to have been a built-in problem in the Busby family.) This tirade then turns on to his sister Kathy – and as he is upset over all these problems the trouble with Christine rises to the fore again – apart from agitated annoyance with Ronald Duncan and George Painter who have not answered particular letters from him despite several reminders! Eventually he sends money to the Busby wife in Africa. However—

3 July: I am towards the end of No. 9 which I now think should be called A HOME OF ONE’S OWN [which actually became the title of chapter 9].

5 July: I had made the death of Barley (as in S.in S.) a nightmare for Phillip – and completed the book with P’s marriage to that darling dream girl . . . but have decided to let her die as in S. in S. So I have taken out the pages. My intention was to let her die in childbirth later on leaving Phillip with ‘Willie’ her son – this after the death of his cousin.

4 August: [Richard arrives at the Field, and spends a few days cutting and clearing grass and tidying everything up.] I read him the scrapped ending of No. 9 – Ph. & Barley married - & his reaction gave me help in deciding to retain it. [Which he had obviously intended so to do!]

On 9 August HW & Richard left for Ireland to stay with John Heygate at his estate at Bellarena. They returned on 26 August. Proofs of No. 8, A Test to Destruction, should have arrived on 8 August but did not (so anxiety & he cannot write) until 5 September – he was then proof reading these until 17 September.

22 September: Received typing of Part I of Moon from E. Tippett. [Note the title is now established but no detail has appeared about this.]

The diary is then blank until:

31 December: New Year’s Eve. I have been too busy (tired) writing The Innocent Moon, etc etc, to write in this journal.

19 January 1961: Have been working continuously during & since Christmas 10 hours a day, 7 days a week, on revision and redesigning No. 9 novel. At 4 p.m. left to see Elizabeth Tippett near Launceston to find if the missing pages (3) are with her. They were. Returned at 1 am. Exhausted.

20 January: Took ‘Poody’ back to Exeter Choir School. Went over Dartmoor to S. Devon coast to see again locale of No. 9 [note than he had evidently visited the area previously]. Decided South Milton would do for the village where Phillip lives – to be called Malandine.

Christine read the typescript for errors and story-line sequence, and is noted as being a great help.

On 15 February HW was in London where he had dinner with E. M. Forster at the Authors’ Club; the following day he sat for his portrait by Bill Thomson (husband of his daughter Margaret).

Then on 17 February HW met John Gawsworth. (For background on this curious episode within HW’s life, see AW, ‘Following a Wild Goose Chase: HW, the King of Redonda, and Wilfrid Ewart’s Way of Revelation’, HWSJ 47, September 2011, pp. 85-99.)

2 May: My entries this year have been almost nil because I have been working on an average 75 hours a week for 7 days a week. I have written and revised several times No. 10 novel, and have started No. 11. No. 9, the Moon is due in proof on 15 June.

HW went to Ireland for 10 days in July for a wedding at Bellarena (whose is not stated, but it was Dora’s daughter ‘Ros’ (Heygate’s step-daughter) to John Harvey, a wine merchant); and again for a week’s holiday in September, where in Dublin he met Kenneth Allsop, who was to write article ‘on me and my books for Daily Mail’, and spent a couple of nights in Tralee: ‘nice visit’.

But on 28 August 1961 he recorded an incident that caused him much anguish:

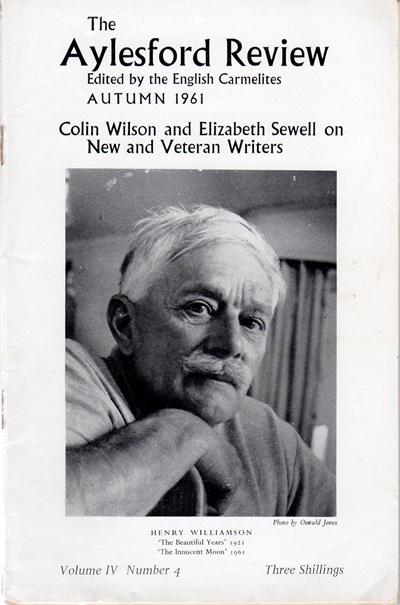

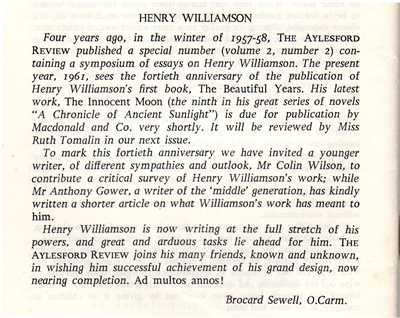

Fr. Brocard [Sewell] recently sent me, at my request, an article on me and my books for the Aylesford Review (October). It was by Colin Wilson & a petty crude piece of work. Inter alia, he wrote that if Richard Aldington wrote HW’s biography on the lines of T.E.L. book, he would prove me to be a congenital liar, etc etc: but, continued the essayist, he himself would not agree with that point of view.

HW had written to Fr Brocard asking him to edit out the more contentious phrases, fearful that the words ‘congenital liar’ would be the only words that would be noticed. Brocard was very reluctant to alter Wilson’s script, but some sort of compromise must have been made as they are not in the printed version. (See The Aylesford Review, Autumn 1961, Vol. IV, No. 4, pp. 131-143, Colin Wilson, ‘Henry Williamson’. This edition also contains an article by Anthony Gower, ‘Living with Henry Williamson’, pp. 145-47: possibly Brocard Sewell thought this would be an antidote to the Wilson piece. The two articles are separated by a full page advertisement for HW’s books by Faber. Brocard Sewell also inserted a personal note of approbation on p. 164.)

HW’s diary contains a further 4 (A5 size) pages of his ‘rationale’ of how this would be received by various journalists and critics: all would basically brand him as a ‘liar’. (In this anguished passage HW reiterates the problem of Malcolm Elwin’s essay in the HW ‘special issue’ of The Aylesford Review, which had rankled badly.)

HW’s main concern was the contradiction of the death of Barley in the Col d’Aubisque avalanche in the Pyrenees as in The Sun in the Sands (1945) – a book which Wilson highlights as ‘one of Williamson’s best books’ and which he seems to have read as totally literal autobiography, although he does point out that it gets rather fanciful towards the end – with the very different scenario in The Innocent Moon, where Barley’s death is just a dream (only for her to die later in childbirth), which would be published at more or less the same time as the Autumn 1961 Aylesford Review containing Wilson’s article. It is possible that Wilson had advance notice of this book (from Brocard Sewell?) prior to publication.

Wilson’s article is interesting as criticism, but it is obvious that he had no real understanding of, or empathy for, HW’s writing. Colin Wilson was himself rather an oddball: the promise of his highly acclaimed The Outsider (1956) evaporated within a plethora of occult studies. HW’s son Richard remembers him as rather unpleasant and violently opinionated. It should be noted too that Wilson was closely associated with Negley and Dan Farson, so his original opinions of HW were no doubt highly coloured by their personal prejudices. Wilson wrote a further article in HWSJ 2, October 1980, pp. 9-20, ‘Henry Williamson and his Writings: A Personal View’, which is in similar vein. But these articles should be read by serious students of HW’s work if only as a point of discussion. Wilson does end the first with:

If they [future Chronicle volumes] have as much success as The Golden Virgin, Williamson will have accomplished one of the greatest artistic pilgrimages of our time.

But in the 1980 essay he states: ‘It was whistling in the dark, and I knew it was.’

HW did not record publication of The Innocent Moon on 27 October, but he mentions sending out a copy to someone on 25 October.

POSTSCRIPT

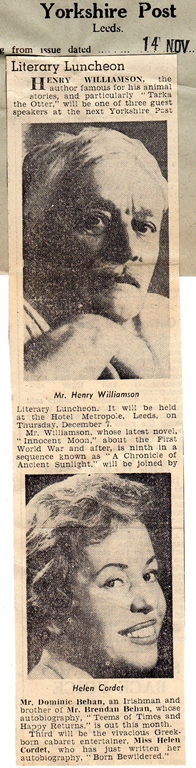

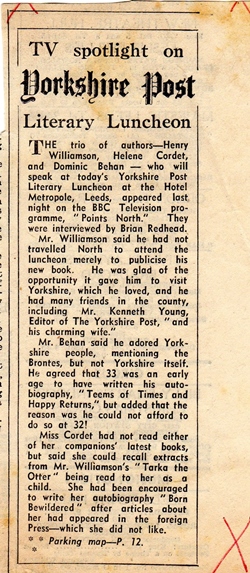

A small selection of cuttings in this file reveals a rather charming incident in HW’s life at the end of 1961. His diary records it thus:

6 December: 1.18pm Kings Cross to Leeds with Foster White [Director, Macdonald Publishers] & Mr. Boardman [unknown to AW]

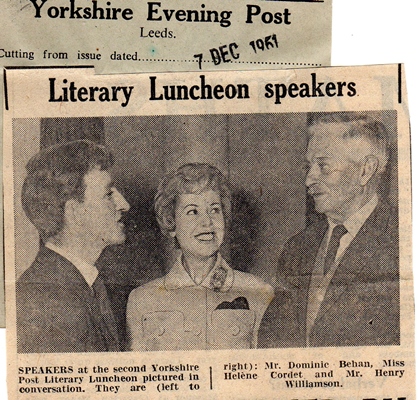

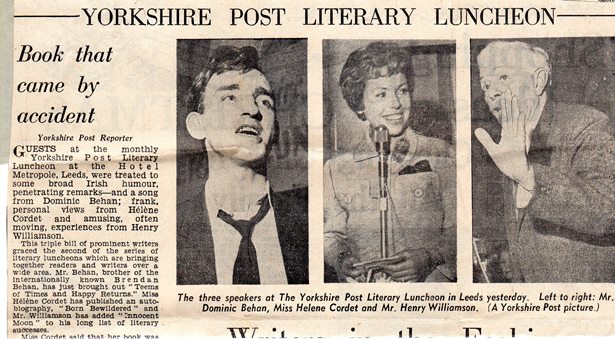

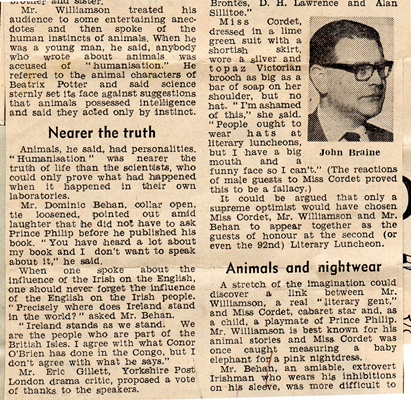

7 December: LEEDS LITERARY LUNCHEON with Dominic Behan & Helene Cordet. Return 4.38 pm, arr. London 8 pm. A.G.M. “PEN”, 37 Charles St., Berkeley Square, – supper.

That this caused quite a stir locally can be seen from the fact that there 8 separate cuttings for the event – a selection of which below:

|

|

*************************

At the end of the previous volume, A Test to Destruction, we left Phillip Maddison demobilised and still in personal crisis but, having determined to become a writer, feeling more optimistic about his future.

The Innocent Moon is divided into four parts, each headed by the name of the main character concerned.

Part One: SPICA VIRGINIS

'Never seek thy love to tell

Love which never told can be'

William Blake

The full verse actually reads:

'Never pain to tell thy love

Love that never told can be

For the gentle wind does move

Silently, invisibly.'

(from ‘MS Notebook’, p. 115)

The reader can deduce a love-story is ahead – and that the path will not be smooth.

The Innocent Moon opens in February 1920 as Phillip and his cousin Willie travel by train to London Bridge, where they say goodbye: Willie is going to France to work for the War Graves Commission (as occurs in the earlier Flax of Dream series), while Phillip continues to his first day ‘as canvasser in the Classified Advertisement Department of the leading morning newspaper in the world’ [i.e. The Times].

He discovers that his work involves trudging round the streets of London trying to obtain adverts from estate agents. After this tiring and dispiriting day he returns home to continue writinge his first book in the ‘Garden Room’ of his grandfather’s house next door, now of course empty. HW is following very closely here what was his own real life experience.

Phillip also keeps a journal (this is akin to HW’s 1920s ‘Richard Jefferies Journal’, but with some different and added entries), and attends the weekly meetings of the literary Parnassus Club run by Mrs Portal-Welch. (This was actually ‘The Tomorrow Club’, run by Mrs. Dawson Scott – which went on to become the famous and long-lasting P.E.N.) Mrs Portal-Welch frequently criticises his writing as ‘wishy-washy’ which depresses him.

But very soon the war evokes itself:

On March 21, second anniversary of the great German attack [i.e. the 1918 Spring Offensive] . . . he was haunted by memories of that morning, two years before . . . Memories of that time, and of comrades lost in battle haunted him until he got to the woods south of Shooting Common . . . then boyhood memories superseded war memories which were too much for him to face in his mind. . . .

Phillip also suffers from nightmares about the war.

At the Parnassus Club he meets Jack O’Donovan who introduces him to the Covent Garden Opera House with its magical ‘Dove’s Nest’. (You will have noted earlier that on 4 May 1960 HW visited this to refresh his memory – to find the Dove’s Nest was no more.)

At a lecture given by ‘a bank-clerk poet called Eliot’ (no prizes for guessing!) Phillip meets a ‘dark, vivid girl’, Tabitha Trevelian. He falls precipitously in love: on a walk into the country at night they see the star Spica Virginis (the brightest star in the constellation Virgo), so he calls her ‘Spica’ (and he is Mars).

Spica is (Gwen)Doline Rendle, with whom HW was deeply in love at this time: a relationship frowned upon by her mother, and further complicated by the fact that she was a cousin of his earlier love Mabs Baker (Eve Fairfax of the novels), with whom he had an affaire when in Folkestone in 1919. Spica lives in Folkestone with her parents but works in a laboratory in Cambridge – as did Doline.

|

| Doline Rendle – she and HW remained lifelong friends |

Phillip continues working, walking, writing. At Whitsun he travels down to Folkestone on his Norton motorcycle to visit Spica but despite spending an idyllic day, she tells him she cannot love him.

Phillip now takes his holiday and travels down to Devon on his Norton, calling to see his Uncle John (Willie’s father) at the family home at Rookhurst. The next day he goes south to the coast (to bathe off Chesil beach – directly south of where Rookhurst has been established see John Akeroyd, ‘The Wiltshire Roots of Rookhurst’, HWSJ 49, September 2013, pp. 67-74).

Continuing west along the south coast (although he is on his way to Willie’s cottage on the north Devon coast) he stops on a ridge where he is startled by:

the sight of the dark mass of a church on the horizon, with a shortened spire on its western end. It was as prominent a landmark as the church on the Passchendaele ridge before the bombardment of Third Ypres.

(Members of the HWS recently visited the area and stopped at that same spot, reading this passage in the novel.) Phillip continues and finds himself in the village of Malandine. He is attracted to the place and spends the night there, next day continuing up to Willie’s cottage which he finds depressing damp and derelict. He therefore returns to Malandine, where he decides to rent ‘Valerian Cottage’ at £5 a year. ‘Malandine’, as you will have seen in the earlier notes, is South Milton, near Hope Cove on the south coast of Devon (for background see AW, ‘Malandine and Barley’, HWSJ 46, September 2010, pp. 48-55).

Phillip sends a telegram to Jack O’Donovan to join him, and buys some basic furniture. But he soon finds he and Jack have a different outlook on life. O’Donovan was actually Jack Donohue, who visited Skirr Cottage in 1920.

|

|

|

| Jack Donohue and a gaunt-looking HW at Skirr Cottage in 1920 | ||

When Jack leaves, Phillip rides across Dartmoor and on to Lynmouth to call on his Aunt Dora, then continues in pouring rain right across country to visit Spica in Cambridge, arriving looking like the proverbial drowned rat to find her surrounded by undergraduates and rather shocked to see him. (HW relates this embarrassing visit in the 1920 diary, and refers to it more than once.)

Back at work he is offered the chance to write ‘Light Car Notes’ for the Weekly Courier and increasingly, does short nature articles also. (These real articles are all published in The Weekly Dispatch, ed. John Gregory, HWS, 1983 – revised edition, re-titled On the Road, available as an e-book.)

Cousin Willie arrives back from France with an article he has written about the Concentration German Graveyard in France. This is a harrowing piece on the need for understanding between Nations: it is an emotional version of HW’s earlier The Wet Flanders Plain (1928).

Black, black, black, vast and terrible, the charred forest sweeps over the horizon. . . . Larks sing above in the blue sky; the larks have always sung. Now they sing above the monuments, black as charred thistles . . .

Here is the spirit of revenge, which will call forth equal revenge, so that men will march again, and fall once more upon the fields of Europe. . . .

Once these were men who, having marched where they were ordered, and having done what they were commanded, after endurance and suffering, fell, and were lost.

The editor cannot take it: ‘If we ran this it might start the war yer talk about.’ But he does give Willie a job on the same terms as Phillip.

Phillip again goes down to Folkestone to see Spica, incidentally meeting Lionel and Eve Fairfax (from the earlier The Dream of Fair Women). He and Spica spend a day on Romney Marsh but the day ends with a family quarrel; Spica’s mother makes it quite clear that she does not like him and asks him to leave. Asking Spica once more if she loves him and will marry him, she says no. Phillip goes off to wander the Leas (as Willie had done over Eve, and indeed Phillip in A Test to Destruction, also over Eve!), where he is found by a concerned Willie.

Back in London neither Willie nor Phillip are getting on very well with their career in journalism. Willie leaves – Phillip is shortly made redundant, following which he mooches about, walking, seeing friends (old and new with some amusing incidents), freelancing – but mainly working on his novel, which is eventually accepted for publication

Part Two: JULIAN

'Fierce midnights and famishing tomorrows'

Algernon Charles Swinburne

Swinburne (1837-1909) was a Romantic-Classicist but also an innovator. A friend of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (and other Pre-Raphaelites), his work shows obvious literary, rebellious, classical, medieval and romantic traits.

HW’s quotation is from the poem ‘Dolores’, published in Poems and Ballads (1866). ‘Dolores’ is subtitled ‘Notre Dame des Sept Douleurs’ (Our Lady of Seven Sorrows) and presents the flip side, as it were, a rather warped version, of ‘the sacred feminine’ or mother goddess – woman as mystical force. Swinburne’s Dolores has ‘seventy times seven’ sins and seems to be someone setting sexual traps for the unwary.

HW’s purpose in using this particular quotation is not at all clear. Yes, Julian is obsessed with Swinburne, and indeed himself has ‘Fierce midnights and famishing morrows’, but there is almost certainly more to it than that. In this section, Phillip (as did HW) meets two women, both married with children (each has a young daughter still at school) and both without husbands. Both women ostensibly fit the idea of ‘sacred feminine’ or mother goddesses and are looking for a (sexual) partner (thus following the theme outlined above), particularly Mrs Selby Lloyd, as will be seen: both here in the novel and in real life.

Julian Warbeck, whom we have already met in The Dream of Fair Women and A Test to Destruction, is based on Frank Davis, a First World War pilot, who was no doubt suffering from shellshock or post-war distress trauma at this time. HW does not tell us this openly, but on p. 216 we learn Julian is writing poetry: ‘about the War, wherein he identified himself with the men he had killed in air-battle’. That Julian identified himself with Swinburne is evident (indeed he is more or less a personification of Swinburne).

|

|

Frank Davis – a studio portrait taken in the early 1920s |

The events of Part Two are based pretty firmly on HW’s real-life situation – except that it all took place in Skirr Cottage in Georgeham. The ‘Malandine’ situation is purely imaginary although based in every detail on South Milton.

*************************

Phillip, having received the news that his novel has been accepted, hurries home to tell his parents, but his father is waiting for him to tell him that his behaviour is intolerable (late nights etc.) and he must leave the family home forthwith. Faced with this dilemma Phillip decides to go down to Devon to live immediately.

(I am now sure that, although HW and his father did not get on, no such final ultimatum quarrel happened. From various clues in HW’s private papers the move to Devon had actually been planned for some time, and he was waiting for the acceptance of his first novel before going ahead.)

Phillip is due to attend a prestigious literary party that evening at the home of J. D. Woodford (J. D. Beresford, the writer-critic who had recommended HW’s first book to Collins). He goes round to Julian Warbeck’s home where Julian’s father and aunt are very kind to him and invite him to stay the night. At the party he meets Walter Ramal (Walter de la Mare) and J. C. Knight (Jack Squire) (both have been prominent in earlier passages in the book).

Back at the Warbeck residence it is decided that Julian should join Phillip in Devon, and that Mr Warbeck will send two guineas a week for his keep.

Next day HW leaves for Devon on his Norton in pouring rain and prepares the damp dingy cottage for Julian’s arrival – which is in a taxi in grand manner; Julian immediately clears off to the pub!

The two men settle into a routine, writing in the morning, walking in the afternoon. In the evening Julian goes to the pub while Phillip continues with work. There are various racy adventures but they quarrel a great deal, culminating in a mock fight which gets out of hand and ends with Phillip discharging his gun at the cellar door. Phillip now tells Julian to leave and he goes to live with his drinking pal ‘Sailor’ (this is ‘Sailor’ from The Village Book).

Phillip then walks on the sea-shore every afternoon.

He walked in a world that was almost all sea and sky, his feet marring the crystalline foam-nets of wavelets curling against his insteps, while he imagined a sun-spirit walking beside him and completing his life with a sigh. . . . He must let the sun absorb him [in order to write].

He sees the footprints of a girl. Following them he comes across a woman and a young girl. To escape meeting them he rather ostentatiously goes off into the water and climbs on to a rock which looks like the leaning profile of the head of ‘Britannia’ (this is Thurlestone Rock, off Milton Sands).

|

|

'Britannia' Rock, in 2015 (© John Gregory) |

He is hailed by the two women who are worried about the tide coming in. They are Irene Lushington and her daughter Barley. So begins an intense friendship with these two: one separated from her husband and now hounded by the rapacious ‘Ivan the Swede’, with whom she has had an affaire, the other a young girl still at school. He finds them ‘Verbena Cottage’ to rent. But Julian muscles in on the developing friendship, making a complication.

As you can see, this cottage, actually named Collacott, still exists:

|

|

Collacott/Verbena cottage (© Anne Williamson) |

Phillip also meets a family there on holiday: sixteen-year-old Annabelle, her older sister Queenie, younger brother Marcus and their mother, Mrs Sophie Selby-Lloyd. He immediately falls for Annabelle. (The Selby-Llloyds are based on the Stokes family, whom HW met in 1922. See AW, Henry Williamson: Tarka and the Last Romantic, and Edward Stokes, ‘The Owl Club’, HWSJ 47, September 2011, pp. 76-94.)

It is arranged that Phillip will become Barley’s tutor, which mainly consists in walking, and talking about literature. The Selby-Lloyds go home: Phillip is shaken to discover they live at Tollemere Park, once the home of the Kingsmans, his Company Commander from Hornchurch in the war (see The Golden Virgin), now all dead.

Annabelle – Annabelle was gone! Over and over again he played the record of Edgar Allan Poe’s poem set to music. Barley listened too, sitting still in the cottage kitchen, as though without a thought in her head. [There were various settings of ‘Annabel Lee’ by the 1920s.]

Phillip now spends more time with Barley: and out on an excursion to the farm called Barton Hole he finds two young owlets. (The farm, a huge grey edifice set in a valley, really exists: I had a cream tea there during the HWS visit to Milton Sands. Finding the owlets actually happened on Braunton Marsh.)

Julian’s love for Irene comes to an inevitable unhappy end, and after two or three ignominious exits and returns, he finally returns for good to London.

Part Three: ANNABELLE

'She was a child, and I was a child

In a kingdom by the sea—'

Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-49), American short-story writer and poet, married his thirteen-year-old cousin in 1836. She died in 1847. Poe wrote his poem ‘Annabel Lee’ in 1849, himself dying soon after. It is a most terribly tragic poem mourning the death of his young bride, and hardly fits the circumstances here other than for the literal meaning of the lines quoted and the coincidence of the name. It may be that HW did not understand the full tragedy of this poem and thought it was only about lost love. The first verse relates:

'It was many and many year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden lived there whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee;

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to love, and be loved by me.'

The poem does fit of course, HW’s idea of and longing for a ‘perfect female being’, which he never achieved.

This part opens with a passage about Way of Revelation, the renowned novel of the Great War by Wilfrid Ewart which Phillip is reading. ‘It was magnificent, it was the real stuff.’ The book had been published in November 1921 to great acclaim. HW’s copy is inscribed: ‘Henry Williamson, Skirr Cottage, March 1922.’ So HW was indeed reading this book at the same moment of time as is Phillip in the novel.

HW made much of this book in his ‘Reality in War Literature’ essay printed in The Linhay on the Downs & Other Adventures (1934). But his inclusion of it here was no doubt prompted by the extraordinary meeting he had on 17 February 1961 with John Gawsworth (the eccentric self-styled King of Redonda), who had championed Ewart for many years and who now handed over Ewart archive material to HW. (See Anne Williamson, ‘Following A Wild Goose Chase’, HWSJ 47, September 2011, pp. 85-99 for the full story.)

Following this passage Phillip muses about his own first book – and accurately quotes its reviews. Now (in 1922) he has finished his second novel.

Irene and Barley have left, precipitously in flight from the dreaded Ivan who had discovered where they were living. But he has had a friendly letter (he thinks loving) from Annabelle, now back at school.

His mother writes with a tale of woe about his Uncle Charlie, who is upset about Grandfather Turney’s Will and his non-receipt of the diamond ring left to him. Phillip is distracted by worry over what action to take – and does nothing. But mainly he is not eating properly and is depressed.

An invitation arrives from his war-time comrade and friend Denis Sisley, now married, who has read Phillip’s book and now invites him to stay for Christmas and hunting afterwards. Sisley lives near Chelmsford (near to Tollemere Park, home of the Selby-Lloyds).

Phillip stops off in London to hand in the typescript of his second book to J. D. Woodford and to visit his parents, which quickly becomes a strain. Then on to Essex, and Christmas with the Sisleys. His mount for the Boxing Day Hunt is rather poor and lands him in trouble fairly quickly, but he inevitably meets up with Sophie and Annabelle who invite him over, and he then spends a great deal of time with them. We have a love triangle with a difference: Sophie is in love with him but he is in love with Annabelle.

With nothing achieved he eventually returns to Devon; Sophie arranges to take a house close by for the summer holidays, when Phillip and Annabelle are partners in a local tennis tournament: an event from real life.

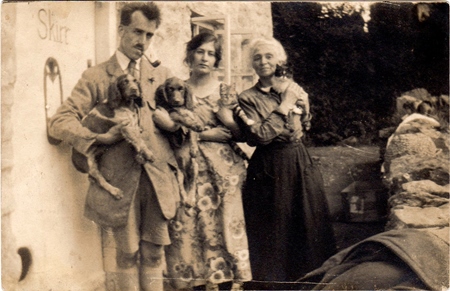

Phillip’s mother and sister Doris come to stay along with Bob Willoughby (again as in real life).

|

| Bill Busby, Biddy and Gertrude Williamson |

Phillip’s tangled emotions continue to see-saw (she loves me – she loves me not).

A fancy-dress dance is organised locally. Phillip decides to go as an owl:

The lower half of his fancy dress consisted of pyjama bottoms . . . to which masses of mixed feathers were stuck with seccotine . . . a white-washed face with burnt-cork circles round eyes surrounded by gummed-on bantams feathers. On his head he wore a baby’s woollen cap pierced by two upstanding turkey feathers . . . a moth-eaten lambskin wound round with old rope to make the shape of a rat . . . carried in his mouth.

The locals were not amused – and he is asked to leave the tennis club! This episode did indeed happen, and HW was ostracised by the village worthies because of it. Sadly there is no photograph of this wonderful get-up!

Mortified he goes to see Annabelle, who is in bed and who kisses him fervently: later he is alone with Sophie, who tries to seduce him. Annabelle now has to return to school. In due course Sophie invites him back to Tollemere for their Hunt Ball. She now seems to be involved with General ‘Bay’ Gotley. The situation is very uneasy and strained: Phillip’s thoughts keep turning to the Kingsmans, Father Aloysius and Julian Grenfell’s poem ‘Into Battle’. He dances with Cynthia, daughter of the General, and realises that the General is actually the father of his adjutant Harry Gotley, killed in April 1918. Phillip had written the kindest of letters to the General at that time. They reveal to Sophie that Phillip was a colonel and had won the DSO, and so is a hero.

Phillip returns to London where he goes to see Martin Beausire, who had reviewed his first book enthusiastically. (Beausire is S. P. B. Mais, prolific writer and long-term friend: see Robert Walker, ‘S. P. B. Mais – Henry’s Longest Literary Relationship’, HWSJ 49, September 2013, pp. 35-53.)

Wandering around London, Phillip fortuitously meets up with Irene and they go to the Parnassus Club together, where Phillip meets several old friends including Mrs Portal-Welch who is about to expand the club (into what became the very famous international P.E.N.).

Phillip stays at his family home writing, but a family row brews up because Bob Willoughby, courting Doris, constantly stays very late to Richard’s rage. He asks Bob to leave, so Doris also leaves and is told never to darken the door again. These two get married four days later.

Willie arrives back from walking in the battlefields. They see Julian and all go for a walk. When Willie leaves for Devon, they go also. They go via Malandine across Dartmoor, but abandon walking due to the weather. Arriving at Appledore, Willie is to cross over by fishing boat to get to his ‘Rat’s Castle’ home. (And so the connection is made with The Pathway, melding the story-lines in masterly fashion – and of course with an added frisson for any reader of this book, who would already know of Willie’s eventual fate.)

Phillip decides he will go back to London (to get away from Julian), but Julian also goes back. In London Phillip escapes and, contacting Sophie, goes back to Tollemere. She now succeeds in seducing him, though ‘Bay’ is still in evidence.

Annabelle arrives home: they play tennis and feed the ducks and she ‘seems’ to be in love with him, but behaves rather oddly. Sophie then tells him that the family (plus General Gotley) are about to leave for the Pyrenees for Easter, and that Annabelle has a ‘beau’ who will also be going with them. Phillip leaves in the middle of the night, pushing a note for Annabelle under her door with a quotation (not given) from Lovelace’s ‘To Lucasta’, but then retrieves it. (Richard Lovelace, 1618-58, poet and Royalist, ‘To Lucasta’, written while imprisoned: the lines that HW refers to are the famous: ‘I could not love thee, Dear, so much / Loved I not Honour more.’)

Part Four: BARLEY

‘True love is likeness of thought.’

Richard Jefferies in Amaryllis at the Fair

Returning to London Phillip calls again on Martin Beausire (obviously relating his woes), who tells him his friends Bevan Swann and Rowley Meek are planning to walk in the Pyrenees to follow the great walk once undertaken by their hero, Hilaire Belloc (related in The Pyrenees,1909).

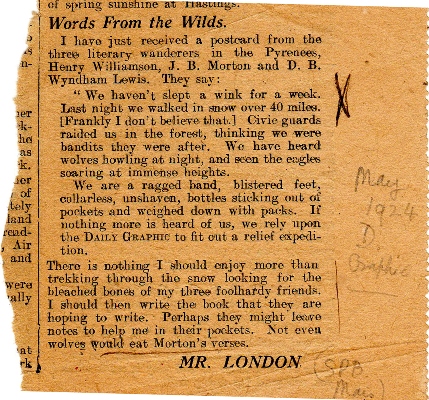

In May 1924 HW actually went on a walking holiday in the Pyrenees with D. B. (Dominic Bevan) Wyndham Lewis and J. B. (Johnny) Morton, both of whom, one after the other, wrote the well-known humorous ‘Beachcomber’ column in the Daily Express. S. P. B. Mais reported on their progress in his gossip column in the Daily Graphic:

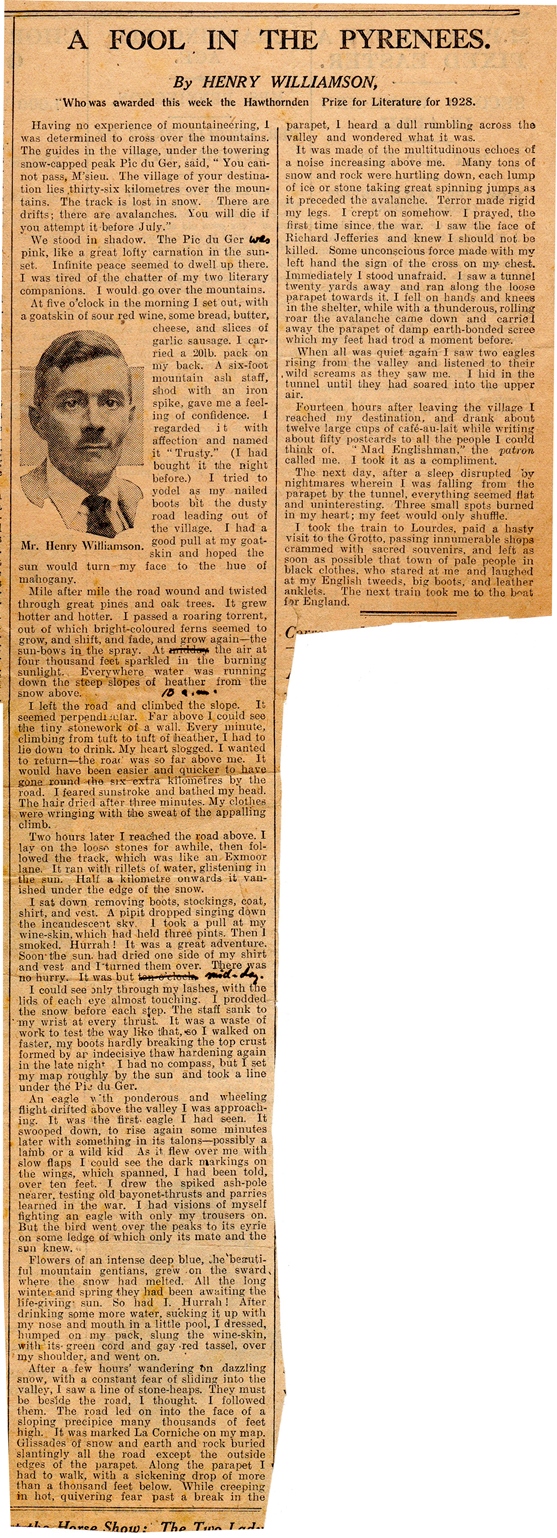

HW subsequently wrote an article based on his experiences during this holiday, although it was not published until four years later. Neither the newspaper nor the precise date it appeared is known, but readers of The Sun in the Sands and The Innocent Moon will recognise the content:

(HW also went on a skiing holiday in January 1929 in the Pyrenees with his friend ‘Kit’ Williams, composer, arranger and writer – for example, The High Pyrenees: Summer and Winter (Wishart, 1928) and Winter Sports in Europe (Bell, 1929). Christopher à Becket Williams (1890-1956) appears as ‘Becket Scrimgeour’ in later volumes of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, particularly The Phoenix Generation. Three postcards from HW to his mother survive, which are reproduced on a separate page.)

Rowley exclaims with great exuberance: ‘We shall hear Roland’s ghostly horn in the Pass of Roncesvalles’.

(This is reference to the medieval verse romaunce ‘The Song of Roland’, telling the epic tale about Charlemagne and Roland: when brave Roland is besieged he blows his horn as arranged, to summon assistance, but no one comes. This is mentioned in Shakespeare’s King Lear, and was also the subject of a powerful poem by Browning, ‘Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came’, echoed in modern times by Louis McNeice (1907-63) in his play Dark Tower, produced on the radio in 1947 – a classic of the genre, with music by Benjamin Britten. HW listened to the first broadcast after returning from a Britten concert!)

There follows a hilarious passage of high-jinks: singing, dancing and shouting from a taxi through the streets of London. Phillip kits himself out in clothes suitable for walking and camping in icy and snow-covered mountains, and is rather disconcerted to find when he meets up with the others (they are four in all) that they are in normal ‘town’ clothes. He realises why once they start to walk, and sends his thick gear home!

He enjoys the journey, but as they all meet up it becomes a loud and noisy affair. It ends up with a wild and hair-raising ride in a black Hispano-Suiza taxi with a drunken driver, who takes them up the mountain.

About midnight they were standing in unreal moonlight on the crest of the pass . . . Far below lay the valley where Roland, ‘the temples of his brain broken’, blew his horn for help that never came. [They set off] . . . walking was unreal in the white and timeless night.

So they walk (and eat and drink!), and by the end of the week arrive at Laruns, where live Irene and Barley. Phillip goes to see them and tells them his plan of walking across the Col d’Aubisque to Argelès Gazost (where the Selby-Lloyds are staying; but he keeps quiet about that). They point out that the Col d’Aubisque is still blocked by snow and is closed until July. But he is determined to continue. Barley works out that Annabelle is involved, and tries to stop him.

Against all advice he decides to continue via la Corniche alone. To avoid the length of the winding mountain road he decides to climb straight up. The description of this perilous ascent in the burning mid-day sun and his ensuing difficult progress along the snow-blocked route is superbly dramatic (and totally imagined – this did not happen to HW!).

He eventually comes to a total block and has to crawl along an unsafe parapet, when he hears a rumble:

The rumbling was made by the multitudinous echoes of an avalanche. . . . [ In terror] He saw the face of Francis Thompson quite near him in the sunshine.

He makes the sign of the cross; terror leaves him; he sees a tunnel and just manages to get into it as the avalanche carries away the parapet he was on just seconds before.

When all was quiet again he listened to the mewing of two eagles soaring across the valley below.

(That totally understated sentence is the mark of a master craftsman.)

Once recovered, he realises that, however perilous, his only course is to continue. Eventually he realises that he will get through. He thinks of Annabelle and his plan to ask her to marry him – and realises she is not his true love. On arrival he washes, rests, and has some food, and goes off to find the hotel the Selby-Lloyds are in. They are all at dinner, so he waits. But he is not made to feel welcome. They are unaware of his adventure other than the fact that he says he walked across the Corniche, which none of them believe.

When he finally gets to sleep he has a nightmare of falling off the Corniche, then finds a gendarme and the proprietor are shaking him. Irene is on the phone and tells him that Barley had set out to stop him crossing the Corniche and has been found dead with her back broken in a fall. This is just all part of his nightmare. But then Irene does phone: to ask if he is all right as Barley has had a dream that Phillip has fallen and broken his back. She asks him to come back to them.

He returns to Laruns by train, stopping off at Lourdes (which he finds a very disappointing place). On meeting Barley they declare their love for each other – but agree to wait until she is eighteen.

Phillip returns to England: Irene will rent Verbena Cottage for August. When they arrive he and Barley wander around together, visiting the cliffs he calls Valhalla. His sister Doris and husband Bob arrive also – Bob confides that their marriage has not been consummated. Phillip thinks Doris never got over the death of their cousin Charlie Pickering.

Spica also comes for a brief visit and offers to make the wedding ring, as she now works for a jeweller. A letter arrives from Willie expressing his deep unhappiness over his love for Mary Ogilvie. Barley urges him to visit, and when Irene and Barley have left to go back to France Phillip writes to Julian, inviting him to visit and walk across Dartmoor to see Willie.

They spend the evening together, then Willie leaves to return to France. He plans to hail a fishing boat to cross the estuary. But we learn he and his dog have been drowned – as at the end of The Pathway – so neatly tying the two series together. Phillip arranges for Willie’s body to be buried at Rookhurst and attends the funeral; Mary Ogilvie too distraught. Uncle John tells Phillip he is now the heir, and that he and Uncle Hilary hope Phillip will live there and farm.

After Christmas Barley arrives in London to visit Phillip’s parents. When she has to return to France and her finishing school Phillip escorts her to Victoria to catch the boat-train (where they see Spica).

But at the last minute they decide to get married immediately and Barley jumps off the train. Four days later they are married at Caxton Hall with his mother and Mrs Neville as witness. They travel down to Malandine to start married life together.

The volume ends with Phillip reciting to Barley the Francis Thompson poem from Sister Songs which contains the words of the title ‘The Innocent Moon’ (which is quoted at the beginning of this entry).

*************************

Between 2000 and 2002 Peter Lewis, a longstanding and dedicated member of The Henry Williamson Society, researched and prepared indices of the individual books in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight series (the first three volumes being indexed together). Originally typed by hand, copies were given only to a select few. His index to The Innocent Moon is reproduced here in non-searchable PDF format, with his kind permission. It forms a valuable and, indeed, unique resource. The synopsis (with Peter Lewis's delightfully idiosyncratic asides) is not included, as essentially it repeats information already given in the consideration above.

*************************

Click on link to go to Critical reception.

*************************

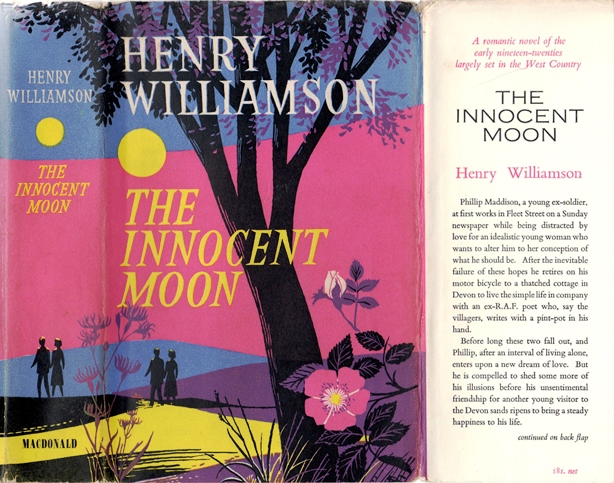

The dust wrapper of the first edition, Macdonald, 1961, designed by James Broom Lynne:

Other editions:

|

|

|

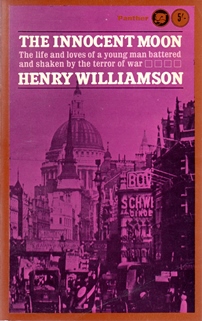

| Panther, paperback, 1965; and back cover | ||

|

|

|

| Macdonald, hardback, 1985 | Sutton, paperback, 1998 |

*************************

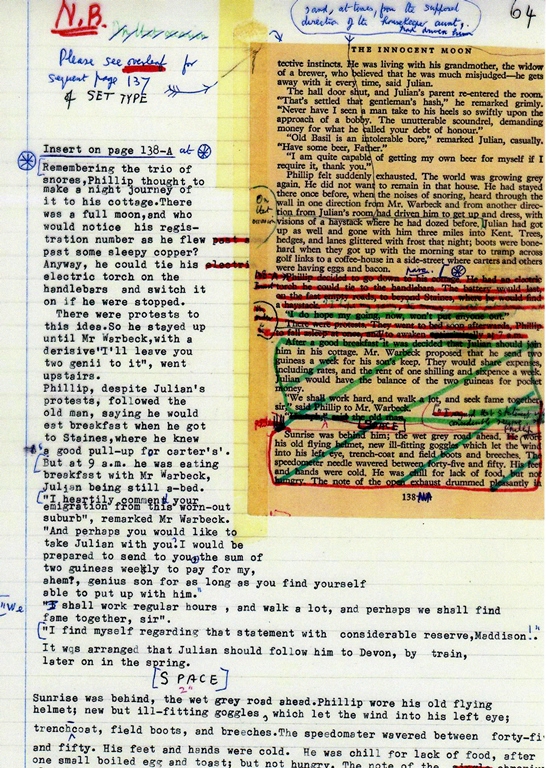

The Panther paperback edition, published in May 1965, is described on the reverse of the title page as being a 'revised edition' (as were several others of the Panther editions of the Chronicle). The revisions are believed to be minor, though no detailed comparison with the text of the first edition has been made. The subsequent reprints by Macdonald and Sutton were of the first edition, so that the humble Panther paperback may well be called the definitive edition.

However, HW did hope to publish a further edition of the book, to be more heavily revised, as evidenced by the Illustration below of an A4 sheet, in which he has used a page from the Panther edition as the basis for further revisions (this is typical of the way in which he worked). In the event these plans came to naught.

*************************

Back to 'A Life's Work' Back to 'A Test to Destruction' Forward to 'It was the Nightingale'